Category: Recommended Reading

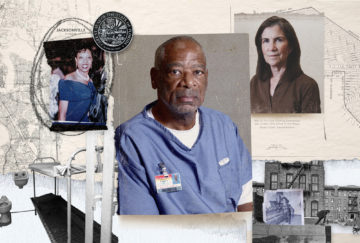

The Mercy Workers

Maurice Chammah at The Marshall Project:

The United States has inherited competing impulses: It’s “an eye for an eye,” but also “blessed are the merciful.” Some Americans believe that our criminal justice system — rife with excessively long sentences, appalling prison conditions and racial disparities — fails to make us safer. And yet, tell the story of a violent crime and a punishment that sounds insufficient, and you’re guaranteed to get eyerolls.

The United States has inherited competing impulses: It’s “an eye for an eye,” but also “blessed are the merciful.” Some Americans believe that our criminal justice system — rife with excessively long sentences, appalling prison conditions and racial disparities — fails to make us safer. And yet, tell the story of a violent crime and a punishment that sounds insufficient, and you’re guaranteed to get eyerolls.

In the midst of that impasse, I’ve come to see mitigation specialists like Baldwin as ambassadors from a future where we think more richly about violence. For the last few decades, they have documented the traumas, policy failures, family dynamics and individual choices that shape the lives of people who kill. Leaders in the field say it’s impossible to accurately count mitigation specialists — there is no formal license — but there may be fewer than 1,000. They’ve actively avoided media attention, and yet the stories they uncover occasionally emerge in Hollywood scripts and Supreme Court opinions. Over three decades, mitigation specialists have helped drive down death sentences from more than 300 annually in the mid-1990s to fewer than 30 in recent years.

More here.

This Changes Everything

Ezra Klein at the New York Times:

In 2018, Sundar Pichai, the chief executive of Google — and not one of the tech executives known for overstatement — said, “A.I. is probably the most important thing humanity has ever worked on. I think of it as something more profound than electricity or fire.”

In 2018, Sundar Pichai, the chief executive of Google — and not one of the tech executives known for overstatement — said, “A.I. is probably the most important thing humanity has ever worked on. I think of it as something more profound than electricity or fire.”

Try to live, for a few minutes, in the possibility that he’s right. There is no more profound human bias than the expectation that tomorrow will be like today. It is a powerful heuristic tool because it is almost always correct. Tomorrow probably will be like today. Next year probably will be like this year. But cast your gaze 10 or 20 years out. Typically, that has been possible in human history. I don’t think it is now.

Artificial intelligence is a loose term, and I mean it loosely. I am describing not the soul of intelligence, but the texture of a world populated by ChatGPT-like programs that feel to us as though they were intelligent, and that shape or govern much of our lives.

more here.

4 Tests Reveal Bing AI ≈ 114 IQ

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xFvDJnf0GXs&ab_channel=AIExplained

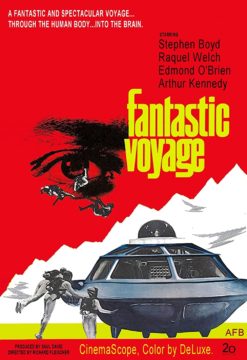

Is The Rectum A Cinema?

David Serlin at Cabinet Magazine:

In Richard Fleischer’s 1966 film Fantastic Voyage, an elite crew of medical technicians—including the buxom but brainy Cora Peterson (Raquel Welch)—is shrunken down to microscopic size and climbs aboard the Proteus, a nano-sized submarine. The crew’s mission: to use a modified laser to destroy a blood clot on the brain of a dying scientist who holds important Cold War military secrets. Navigating their way through the dark, dangerous world of multicellular marauders and bacterial invaders, the crew of the Proteus spends a good amount of time on-screen peering out the windows in awe of the human body’s oceanic interior. Just after completing their assignment, and with valuable seconds ticking away, the crew of the Proteus is attacked by white blood cells. The survivors exit the body by riding out through a tear duct, cushioned in the saline safety of a single teardrop.

In Richard Fleischer’s 1966 film Fantastic Voyage, an elite crew of medical technicians—including the buxom but brainy Cora Peterson (Raquel Welch)—is shrunken down to microscopic size and climbs aboard the Proteus, a nano-sized submarine. The crew’s mission: to use a modified laser to destroy a blood clot on the brain of a dying scientist who holds important Cold War military secrets. Navigating their way through the dark, dangerous world of multicellular marauders and bacterial invaders, the crew of the Proteus spends a good amount of time on-screen peering out the windows in awe of the human body’s oceanic interior. Just after completing their assignment, and with valuable seconds ticking away, the crew of the Proteus is attacked by white blood cells. The survivors exit the body by riding out through a tear duct, cushioned in the saline safety of a single teardrop.

For all its retrospective camp value, Fantastic Voyage is also a fascinating cultural hybrid, the talented offspring of postwar American cinema and postwar American science.

more here.

Margaret Atwood’s ‘Old Babes in the Wood’ tackles what it means to be human

Gabino Iglesias in NPR:

Margaret Atwood, without a doubt one of the greatest living writers, is best known for her incredibly successful and award-winning novels The Handmaid’s Tale and, more recently, The Testaments. However, she is also an extraordinary short story writer — and Old Babes in the Wood, her first collection in almost a decade, is a dazzling mixture of stories that explore what it means to be human while also showcasing Atwood’s gifted imagination and great sense of humor.

Margaret Atwood, without a doubt one of the greatest living writers, is best known for her incredibly successful and award-winning novels The Handmaid’s Tale and, more recently, The Testaments. However, she is also an extraordinary short story writer — and Old Babes in the Wood, her first collection in almost a decade, is a dazzling mixture of stories that explore what it means to be human while also showcasing Atwood’s gifted imagination and great sense of humor.

Old Babes in the Wood contains 15 stories, some of which have previously appeared in The New Yorker and The New York Times Magazine. The collection is divided into three parts. The first and last, titled “Tig & Nell” and “Nell & Tig,” revolve around a married couple and look, more or less, at their entire lives — what they’ve done and felt, the people that left a mark on them, their thoughts. These stories, which taken together feel like a mosaic novella more than literary bookends for a collection, offer a deep, heartfelt, engrossing look at the minutiae of life. The middle part, titled “My Evil Mother,” is perhaps the crowning jewel in this collection and brings together eight unique tales that vary wildly in terms of tone, voice, theme, and format. From imagined interviews and stories told by aliens to the circle of life and a snail trapped in the body of a woman, these tales show Atwood’s characteristic insight and intellect while also putting on full display her ability to make us laugh, her chronicler’s eye for detail, and her unparalleled imagination.

More here.

Aggressive Medical Care Remains Common at Life’s End

Paula Span in The New York Times:

In July, Jennifer O’Brien got the phone call that adult children dread. Her 84-year-old father, who insisted on living alone in rural New Mexico, had broken his hip. The neighbor who found him on the floor after a fall had called an ambulance.

In July, Jennifer O’Brien got the phone call that adult children dread. Her 84-year-old father, who insisted on living alone in rural New Mexico, had broken his hip. The neighbor who found him on the floor after a fall had called an ambulance.

Ms. O’Brien is a health care administrator and consultant in Little Rock, Ark., and the widow of a palliative care doctor; she knew more than family members typically do about what lay ahead. James O’Brien, a retired entrepreneur, was in poor health, with heart failure and advanced lung disease after decades of smoking. Because of a spinal injury, he needed a walker. He was so short of breath that, except for quick breaks during meals, he relied on a biPAP, a ventilator that required a tightfitting face mask. He had standing do-not-resuscitate and do-not-intubate orders, Ms. O’Brien said. They had discussed his strong belief that “if his heart stopped, he would take that to mean that it was his time.”

More here.

Sunday, March 12, 2023

This Is a Philosopher on Drugs

Justin E. H. Smith in Wired:

There is something strange in the disinterest philosophers show for experimentation with mind-altering drugs—or at least for talking about their experimentation publicly. At the margins of philosophical writing, we have Walter Benjamin’s record of his dabblings in hashish and Michel Foucault’s casual admission in interviews that he would rather be dropping acid in the Mojave Desert than sipping wine in Paris. Even further out we have philosophy-curious writers like Thomas de Quincey (also a biographer of Immanuel Kant) recounting his own experience of opium addiction. And then we have probabilities and speculation. The natural philosopher Johannes Kepler likely tried some fly agaric before writing his 1608 treatise of lunar astronomy, the Somnium (read it and you’ll see what I mean). The third-century Neoplatonist philosopher Plotinus might have availed himself of some herbal or fungal supplements to help him achieve his many out-of-body experiences, which he liked to call henosis, or “ecstatic union with the One.”

There is something strange in the disinterest philosophers show for experimentation with mind-altering drugs—or at least for talking about their experimentation publicly. At the margins of philosophical writing, we have Walter Benjamin’s record of his dabblings in hashish and Michel Foucault’s casual admission in interviews that he would rather be dropping acid in the Mojave Desert than sipping wine in Paris. Even further out we have philosophy-curious writers like Thomas de Quincey (also a biographer of Immanuel Kant) recounting his own experience of opium addiction. And then we have probabilities and speculation. The natural philosopher Johannes Kepler likely tried some fly agaric before writing his 1608 treatise of lunar astronomy, the Somnium (read it and you’ll see what I mean). The third-century Neoplatonist philosopher Plotinus might have availed himself of some herbal or fungal supplements to help him achieve his many out-of-body experiences, which he liked to call henosis, or “ecstatic union with the One.”

More here.

Springing forward into daylight saving time is a step back for health – a neurologist explains the medical evidence, and why this shift is worse than the fall time change

Beth Ann Malow at The Conversation:

Researchers are discovering that “springing ahead” each March is connected with serious negative health effects, including an uptick in heart attacks and teen sleep deprivation. In contrast, the fall transition back to standard time is not associated with these health effects, as my co-authors and I noted in a 2020 commentary.

Researchers are discovering that “springing ahead” each March is connected with serious negative health effects, including an uptick in heart attacks and teen sleep deprivation. In contrast, the fall transition back to standard time is not associated with these health effects, as my co-authors and I noted in a 2020 commentary.

I’ve studied the pros and cons of these twice-annual rituals for more than five years as a professor of neurology and pediatrics and the director of Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s sleep division. It’s become clear to me and many of my colleagues that the transition to daylight saving time each spring affects health immediately after the clock change and also for the nearly eight months that Americans remain on daylight saving time.

More here.

Yuval Noah Harari: Israel Is on Its Way to Becoming a Dictatorship

Yuval Noah Harari in Haaretz:

A “coup from above” occurs when a government that came to power in a perfectly legal way, violates the restrictions the law imposes on it, and tries to gain unlimited power. It’s a very old trick: First use the law to gain power, then use power to distort the law.

A “coup from above” occurs when a government that came to power in a perfectly legal way, violates the restrictions the law imposes on it, and tries to gain unlimited power. It’s a very old trick: First use the law to gain power, then use power to distort the law.

It can be very confusing when a “coup from above” takes place. On the face of it, everything looks normal. There are no tanks in the streets, and no general with a uniform sagging with medals interrupts the television broadcasts. The coup occurs behind closed doors, with laws being passed and decrees being signed that remove all restraints on the government, and dismantle all checks and balances. Of course, the government does not declare that it is carrying out a coup. It claims only that it is passing some much-needed reforms, “for the good of the people.”

How can we in Israel today determine whether we are facing a genuine reform or a coup? The simplest test is to ask: Are there still limits on the power of the government?

More here.

Your Literary Guide to the 2023 Oscars

Eliza Smith at Literary Hub:

Sure, we’re a website about books, but that doesn’t mean we can’t get in on the Oscars fun, too. (Exhibit A: If they gave Oscars to books, our 2022 nominees.) And while there are few adaptations in this year’s lineup, we’ll still be tuning in on Sunday to celebrate storytelling, judge the Academy’s taste, and perhaps witness some live drama. In the meantime, we’re recommending the books and films you should read and watch next for each Best Picture contender.

Sure, we’re a website about books, but that doesn’t mean we can’t get in on the Oscars fun, too. (Exhibit A: If they gave Oscars to books, our 2022 nominees.) And while there are few adaptations in this year’s lineup, we’ll still be tuning in on Sunday to celebrate storytelling, judge the Academy’s taste, and perhaps witness some live drama. In the meantime, we’re recommending the books and films you should read and watch next for each Best Picture contender.

More here.

Why It’s Time to Take Electrified Medicine Seriously

Alice Park in Time:

When the disease plaguing her digestive system was at its worst, Kelly Owens once had to rush to the bathroom 17 separate times in the course of a few hours. By the time she was 25, her crippling case of Crohn’s disease had given her arthritis from her ankles all the way up to her jaw and fingertips. The dozens of drugs she took helped a bit, but the brutal side effects included nausea, fatigue and weight gain. Nights were the worst. On good nights, Owens woke up to excruciating pain and couldn’t fall asleep again, trying in vain to find a comfortable position. On bad nights, the diarrhea and vomiting made her so dehydrated, she needed to be hospitalized. “My body was at war with me,” she says. Worse, the powerful drugs she took were weakening her bones: at 25 years old, she had the frail and weakened skeleton of an 80-year-old. There is no known cure for Crohn’s, an inflammatory bowel disease that affects nearly 800,000 people in the U.S. Available medication provides only temporary relief. Owens, who was diagnosed at age 13, eventually developed resistance to all of the drugs she tried, and in February 2017, she says, her doctors told her, “We are out of [treatments] to try; there is nothing left because you have been on them all.”

When the disease plaguing her digestive system was at its worst, Kelly Owens once had to rush to the bathroom 17 separate times in the course of a few hours. By the time she was 25, her crippling case of Crohn’s disease had given her arthritis from her ankles all the way up to her jaw and fingertips. The dozens of drugs she took helped a bit, but the brutal side effects included nausea, fatigue and weight gain. Nights were the worst. On good nights, Owens woke up to excruciating pain and couldn’t fall asleep again, trying in vain to find a comfortable position. On bad nights, the diarrhea and vomiting made her so dehydrated, she needed to be hospitalized. “My body was at war with me,” she says. Worse, the powerful drugs she took were weakening her bones: at 25 years old, she had the frail and weakened skeleton of an 80-year-old. There is no known cure for Crohn’s, an inflammatory bowel disease that affects nearly 800,000 people in the U.S. Available medication provides only temporary relief. Owens, who was diagnosed at age 13, eventually developed resistance to all of the drugs she tried, and in February 2017, she says, her doctors told her, “We are out of [treatments] to try; there is nothing left because you have been on them all.”

Hope for Owens and millions of others experiencing a broad range of previously untreatable, or unsatisfactorily treated, diseases may be near, thanks to a breakthrough that seems more science fiction than medical reality. The remarkable convergence of advances in bioengineering and neurology has resulted in a fast-developing way to treat chronic diseases, known as bioelectronic medicine. These advances allow scientists to identify specific nerves and implant devices that can be activated when needed to stimulate or dial down their activity; that in turn controls cells in organs targeted by those nerves that regulate the body’s many immune and metabolic responses.

More here.

Modular cognition

Levin and Yuste in aeon:

Intelligent decision-making doesn’t require a brain. You were capable of it before you even had one. Beginning life as a single fertilised egg, you divided and became a mass of genetically identical cells. They chattered among themselves to fashion a complex anatomical structure – your body. Even more remarkably, if you had split in two as an embryo, each half would have been able to replace what was missing, leaving you as one of two identical (monozygotic) twins. Likewise, if two mouse embryos are mushed together like a snowball, a single, normal mouse results. Just how do these embryos know what to do? We have no technology yet that has this degree of plasticity – recognising a deviation from the normal course of events and responding to achieve the same outcome overall.

Intelligent decision-making doesn’t require a brain. You were capable of it before you even had one. Beginning life as a single fertilised egg, you divided and became a mass of genetically identical cells. They chattered among themselves to fashion a complex anatomical structure – your body. Even more remarkably, if you had split in two as an embryo, each half would have been able to replace what was missing, leaving you as one of two identical (monozygotic) twins. Likewise, if two mouse embryos are mushed together like a snowball, a single, normal mouse results. Just how do these embryos know what to do? We have no technology yet that has this degree of plasticity – recognising a deviation from the normal course of events and responding to achieve the same outcome overall.

This is intelligence in action: the ability to reach a particular goal or solve a problem by undertaking new steps in the face of changing circumstances. It’s evident not just in intelligent people and mammals and birds and cephalopods, but also cells and tissues, individual neurons and networks of neurons, viruses, ribosomes and RNA fragments, down to motor proteins and molecular networks. Across all these scales, living things solve problems and achieve goals by flexibly navigating different spaces – metabolic, physiological, genetic, cognitive, behavioural.

But how did intelligence emerge in biology?

More here.

Chaim Topol (1935 – 2023) Actor

Francisco Ayala (1934 – 2023) Evolutionary Biologist

Mary Bauermeister (1934 – 2023) Artist

Saturday, March 11, 2023

Everything Is Hyperpolitical

Anton Jäger in The Point:

Anton Jäger in The Point:

The photographs come in a bright, nearly fluorescent hue. Their connecting theme is “love.” In a portrait called Love (hands in hair), a woman with reddish hair and shuttered eyes is clutched by a pair of male hands reaching from outside the frame. In another picture a man in a jean jacket dances alone, almost reaching for a nearby hand. In Love (hands praying), a woman with closed eyes folds her hands amidst a crowd of partygoers. As if in a secular ritual, she meditates in the anonymity of the nightclub. The people in the photographs dance to music modeled on noises emitted by the industrial machinery of Detroit and Manchester, the twin birth cities of techno.

In 1989, however—the year in which these photos were taken—the machines are no longer operative. Most of them have downsized or relocated to China, whereas the twin cities of techno have deindustrialized. Traveling through a Chinese megacity some years before, the German photographer Hilla Becher noticed a reassembled copy of a steel mill she once shot in Europe. Now, the youngsters in Wolfgang Tillmans’s nightlife photographs seek to dance away industry, politics and history itself.

The time and place of Tillmans’s shots are worth noting. They document a Thatcherite London and a Berlin in which the Wall is crumbling. To the east, state socialism is nearing collapse. A fully global capitalism is triumphant. Western deindustrialization is accelerating. Deployed the same year the American political scientist Francis Fukuyama published his fabled essay on “the end of history” in the National Interest, Tillmans’s camera becomes witness to an exercise in collective amnesia: an attempt to banish the ideological specters of the last century and quietly stride into a private utopia. An age of “post-politics” has opened.

More here.

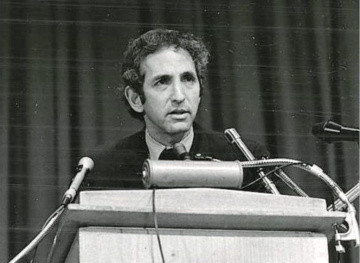

Seymour Hersh on Daniel Ellsberg

Seymour Hersh in Jacobin:

Seymour Hersh in Jacobin:

I think it best that I begin with the end. On March 1, I and dozens of Dan’s friends and fellow activists received a two-page notice that he had been diagnosed with incurable pancreatic cancer and was refusing chemotherapy because the prognosis, even with chemo, was dire. He will be ninety-two in April.

Last November, over a Thanksgiving holiday spent with family in Berkeley, I drove a few miles to visit Dan at the home in neighboring Kensington he has shared for decades with his wife Patricia. My intent was to yack with him for a few hours about our mutual obsession, Vietnam. More than fifty years later, he was still pondering the war as a whole, and I was still trying to understand the My Lai massacre. I arrived at 10 a.m. and we spoke without a break — no water, no coffee, no cookies — until my wife came to fetch me, and to say hello and visit with Dan and Patricia. She left, and I stayed a few more minutes with Dan, who wanted to show me his library of documents that could have gotten him a long prison term. Sometime around 6 p.m. — it was getting dark — Dan walked me to my car, and we continued to chat about the war and what he knew — oh, the things he knew — until I said I had to go and started the car. He then said, as he always did, “You know I love you, Sy.”

So this is a story about a tutelage that began in the summer of 1972, when Dan and I first connected. I have no memory of who called whom, but I was then at the New York Times and Dan had some inside information on White House horrors he wanted me to chase down — stuff that had not been in the Pentagon Papers.

More here.

Curious Stranger

Aditya Bahl in Sidecar:

Aditya Bahl in Sidecar:

July 1957. A 26-year-old Romila Thapar waits at Prague Airport. She is dressed in a sari. The pockets of her overcoat are bulging with yet more saris. ‘It is blasphemous’, she laments in her diary, to have crumpled ‘the garment of the exotic, the indolent, the unobvious, the newly awakening East’. But there is no more room in her suitcases. They are stuffed with photographic equipment (‘cameras, cameras, more cameras’) and saddled with ‘large bundles of books and papers, strapped together with bits of string’. Thapar – today the pre-eminent historian of ancient India – is on her way to China along with the Sri Lankan art historian Anil de Silva and the French photographer Dominique Darbois. Earlier in the year, the Chinese Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries had accepted de Silva’s proposal to study two ancient Buddhist cave sites in the northwestern Gansu province, Maijishan and Dunhuang. After some hesitation, Thapar, then a graduate student at SOAS in London, agreed to join de Silva as her assistant. She had been nervous about her limited expertise in Chinese Buddhist art, as well as the practical difficulties posed by the cave sites. And not without good reason. Just imagine crawling about in those rock-cut caverns ‘enveloped in billowing yards of silk’.

But China was still far away. The three women were waiting for their delayed connection to Moscow. The latest, much-publicized, Soviet plane had got stuck in the mud. Loitering in the terminal, Thapar observed the entourage of the Indian actors, Prithviraj Kapoor and his son Raj, a newly anointed superstar in the Socialist Bloc. As heavy rains poured outside, some members of the group began discussing the film Storm over Asia (‘Would they think it rude if I gently pointed out to them that the film was not by Sergei Eisenstein, but by Vsevolod Pudovkin, and that the two techniques are so different that one can’t confuse them’). Elsewhere, a French family tune into Radio Luxembourg; a young African man listens to the BBC on his radio; the terminal loudspeakers play the Voice of America (‘poor miserable propagandists’). Late into the night, Thapar leisurely smokes her black Sobranie. She thinks of herself ‘an overburdened mule wrapped in folds of cloth’.

More here.

The Evolution of Zaha Hadid

Ashley Gardini at JSTOR Daily:

This month marks seven years since the unexpected passing of the British-Iraqi architect Zaha Hadid, at what was undoubtedly the height of her historic career. Her influence on international architecture can’t be overstated. She was part of a generation of architects who both redefined and invented the forms that would characterize contemporary design. And as an Arab woman garnering international fame, she challenged “who” an architect could be.

This month marks seven years since the unexpected passing of the British-Iraqi architect Zaha Hadid, at what was undoubtedly the height of her historic career. Her influence on international architecture can’t be overstated. She was part of a generation of architects who both redefined and invented the forms that would characterize contemporary design. And as an Arab woman garnering international fame, she challenged “who” an architect could be.

Hadid was born in Baghdad, Iraq, in 1950. She grew up in a cosmopolitan household that was engaged in both politics and the arts. She realized her interest in architecture at an early age and, later in life, connected it to childhood visits to Sumerian cities in the south of Iraq. In the 1970s, Hadid studied mathematics at the American University in Beirut, Lebanon, before moving to London to study architecture at the Architectural Association School of Architecture. There, her work was shaped by her interest in Russian avant-garde movements.

more here.