Scott Alexander in Astral Codex Ten:

The average online debate about AI pits someone who thinks the risk is zero, versus someone who thinks it’s any other number. I agree these are the most important debates to have for now.

But within the community of concerned people, numbers vary all over the place:

- Scott Aaronson says says 2%

- Will MacAskill says 3%

- The median machine learning researcher on Katja Grace’s survey says 5 – 10%

- Paul Christiano says 10 – 20%

- The average person working in AI alignment thinks about 30%

- Top competitive forecaster Eli Lifland says 35%

- Holden Karnofsky, on a somewhat related question, gives 50%

- Eliezer Yudkowsky seems to think >90%

- As written this makes it look like everyone except Eliezer is <=50%, which isn’t true; I’m just having trouble thinking of other doomers who are both famous enough that you would have heard of them, and have publicly given a specific number.

I go back and forth more than I can really justify, but if you force me to give an estimate it’s probably around 33%; I think it’s very plausible that we die, but more likely that we survive (at least for a little while). Here’s my argument, and some reasons other people are more pessimistic.

More here.

Do you want to live a better, healthier and longer life? Me too.

Do you want to live a better, healthier and longer life? Me too. Three years since

Three years since  The truth is that American society has made persistent grief disabling, because the demands that grief makes on a person are at odds with the way that American capitalism expects people to comport themselves as workers. The normal worker, in our economic system, is a person whose ability to work is not impaired by grief—not someone who doesn’t experience loss, which would of course be impossible, but someone who simply doesn’t let it get to them. There is no statutory entitlement to bereavement leave in the United States, except in the state of Oregon. In fact, Department of Labor guidance on the Fair Labor Standards Act explicitly cites mourning as the example par excellence of unprotected non-work: Federal law “does not require payment for time not worked, including attending a funeral.”

The truth is that American society has made persistent grief disabling, because the demands that grief makes on a person are at odds with the way that American capitalism expects people to comport themselves as workers. The normal worker, in our economic system, is a person whose ability to work is not impaired by grief—not someone who doesn’t experience loss, which would of course be impossible, but someone who simply doesn’t let it get to them. There is no statutory entitlement to bereavement leave in the United States, except in the state of Oregon. In fact, Department of Labor guidance on the Fair Labor Standards Act explicitly cites mourning as the example par excellence of unprotected non-work: Federal law “does not require payment for time not worked, including attending a funeral.” Scientists have generated the first complete map of the brain of a small insect, including all of its neurons and connecting synapses.

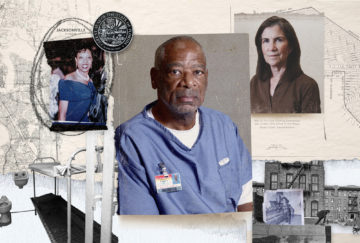

Scientists have generated the first complete map of the brain of a small insect, including all of its neurons and connecting synapses. The United States has inherited competing impulses: It’s “an eye for an eye,” but also “blessed are the merciful.” Some Americans believe that our criminal justice system — rife with

The United States has inherited competing impulses: It’s “an eye for an eye,” but also “blessed are the merciful.” Some Americans believe that our criminal justice system — rife with  In 2018, Sundar Pichai, the chief executive of Google — and not one of the tech executives known for overstatement — said, “A.I. is probably the most important thing humanity has ever worked on. I think of it as something more profound than electricity or fire.”

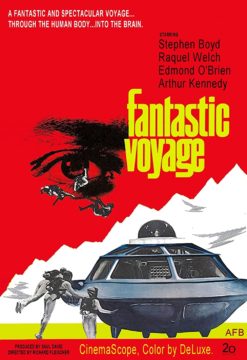

In 2018, Sundar Pichai, the chief executive of Google — and not one of the tech executives known for overstatement — said, “A.I. is probably the most important thing humanity has ever worked on. I think of it as something more profound than electricity or fire.” In Richard Fleischer’s 1966 film Fantastic Voyage, an elite crew of medical technicians—including the buxom but brainy Cora Peterson (Raquel Welch)—is shrunken down to microscopic size and climbs aboard the Proteus, a nano-sized submarine. The crew’s mission: to use a modified laser to destroy a blood clot on the brain of a dying scientist who holds important Cold War military secrets. Navigating their way through the dark, dangerous world of multicellular marauders and bacterial invaders, the crew of the Proteus spends a good amount of time on-screen peering out the windows in awe of the human body’s oceanic interior. Just after completing their assignment, and with valuable seconds ticking away, the crew of the Proteus is attacked by white blood cells. The survivors exit the body by riding out through a tear duct, cushioned in the saline safety of a single teardrop.

In Richard Fleischer’s 1966 film Fantastic Voyage, an elite crew of medical technicians—including the buxom but brainy Cora Peterson (Raquel Welch)—is shrunken down to microscopic size and climbs aboard the Proteus, a nano-sized submarine. The crew’s mission: to use a modified laser to destroy a blood clot on the brain of a dying scientist who holds important Cold War military secrets. Navigating their way through the dark, dangerous world of multicellular marauders and bacterial invaders, the crew of the Proteus spends a good amount of time on-screen peering out the windows in awe of the human body’s oceanic interior. Just after completing their assignment, and with valuable seconds ticking away, the crew of the Proteus is attacked by white blood cells. The survivors exit the body by riding out through a tear duct, cushioned in the saline safety of a single teardrop. Margaret Atwood, without a doubt one of the greatest living writers, is best known for her incredibly successful and award-winning novels The Handmaid’s Tale and, more recently, The Testaments. However, she is also an extraordinary short story writer — and Old Babes in the Wood, her first collection in almost a decade, is a dazzling mixture of stories that explore what it means to be human while also showcasing Atwood’s gifted imagination and great sense of humor.

Margaret Atwood, without a doubt one of the greatest living writers, is best known for her incredibly successful and award-winning novels The Handmaid’s Tale and, more recently, The Testaments. However, she is also an extraordinary short story writer — and Old Babes in the Wood, her first collection in almost a decade, is a dazzling mixture of stories that explore what it means to be human while also showcasing Atwood’s gifted imagination and great sense of humor. In July, Jennifer O’Brien got the phone call that adult children dread. Her 84-year-old father, who insisted on living alone in rural New Mexico, had broken his hip. The neighbor who found him on the floor after a fall had called an ambulance.

In July, Jennifer O’Brien got the phone call that adult children dread. Her 84-year-old father, who insisted on living alone in rural New Mexico, had broken his hip. The neighbor who found him on the floor after a fall had called an ambulance. There is something

There is something Researchers are discovering that “springing ahead” each March is connected with serious negative health effects, including an uptick in

Researchers are discovering that “springing ahead” each March is connected with serious negative health effects, including an uptick in  A “coup from above” occurs when a government that came to power in a perfectly legal way, violates the restrictions the law imposes on it, and tries to gain unlimited power. It’s a very old trick: First use the law to gain power, then use power to distort the law.

A “coup from above” occurs when a government that came to power in a perfectly legal way, violates the restrictions the law imposes on it, and tries to gain unlimited power. It’s a very old trick: First use the law to gain power, then use power to distort the law. Sure, we’re a website about books, but that doesn’t mean we can’t get in on the Oscars fun, too. (Exhibit A: If they gave Oscars to books,

Sure, we’re a website about books, but that doesn’t mean we can’t get in on the Oscars fun, too. (Exhibit A: If they gave Oscars to books,  W

W Intelligent decision-making doesn’t require a brain. You were capable of it before you even had one. Beginning life as a single fertilised egg, you divided and became a mass of genetically identical cells. They chattered among themselves to fashion a complex anatomical structure – your body. Even more remarkably, if you had split in two as an embryo, each half would have been able to replace what was missing, leaving you as one of two identical (monozygotic) twins. Likewise, if two mouse embryos are mushed together like a snowball, a single, normal mouse results. Just how do these embryos know what to do? We have no technology yet that has this degree of plasticity – recognising a deviation from the normal course of events and responding to achieve the same outcome overall.

Intelligent decision-making doesn’t require a brain. You were capable of it before you even had one. Beginning life as a single fertilised egg, you divided and became a mass of genetically identical cells. They chattered among themselves to fashion a complex anatomical structure – your body. Even more remarkably, if you had split in two as an embryo, each half would have been able to replace what was missing, leaving you as one of two identical (monozygotic) twins. Likewise, if two mouse embryos are mushed together like a snowball, a single, normal mouse results. Just how do these embryos know what to do? We have no technology yet that has this degree of plasticity – recognising a deviation from the normal course of events and responding to achieve the same outcome overall.