Ross Douthat in The New York Times:

This week the conservative writer Bethany Mandel had the kind of moment that can happen to anyone who talks in public for a living: While promoting a new book critiquing progressivism, she was asked to define the term “woke” by an interviewer — a reasonable question, but one that made her brain freeze and her words stumble. The viral clip, in turn, yielded an outpouring of arguments about the word itself: Can it be usefully defined? Is it just a right-wing pejorative? Is there any universally accepted label for what it’s trying to describe? The answers are yes, sometimes and unfortunately no. Of course there is something real to be described: The revolution inside American liberalism is a crucial ideological transformation of our time. But unlike a case like “neoconservatism,” where a critical term was then accepted by the movement it described, our climate of ideological enmity makes settled nomenclature difficult.

This week the conservative writer Bethany Mandel had the kind of moment that can happen to anyone who talks in public for a living: While promoting a new book critiquing progressivism, she was asked to define the term “woke” by an interviewer — a reasonable question, but one that made her brain freeze and her words stumble. The viral clip, in turn, yielded an outpouring of arguments about the word itself: Can it be usefully defined? Is it just a right-wing pejorative? Is there any universally accepted label for what it’s trying to describe? The answers are yes, sometimes and unfortunately no. Of course there is something real to be described: The revolution inside American liberalism is a crucial ideological transformation of our time. But unlike a case like “neoconservatism,” where a critical term was then accepted by the movement it described, our climate of ideological enmity makes settled nomenclature difficult.

I personally like the term “Great Awokening,” which evokes the new progressivism’s roots in Protestantism — but obviously secular progressives find it condescending. I appreciate how the British writer Dan Hitchens acknowledges the difficulty of definitions by calling the new left-wing politics “the Thing” — but that’s unlikely to catch on with true believing Thingitarians. So let me try a different exercise — instead of a pithy term or definition, let me write a sketch of the “woke” worldview, elaborating its internal logic as if I myself believed in it. (To the incautious reader: These are not my actual beliefs.)

More here.

Gardiner Means in Phenomenal World:

Gardiner Means in Phenomenal World: Pranab Bardhan in Boston Review:

Pranab Bardhan in Boston Review: Susan Neiman in Unherd:

Susan Neiman in Unherd: Malcom Kyeyune in Compact Magazine:

Malcom Kyeyune in Compact Magazine: O

O “

“ Tompkins produced two fine books in the 1990s, “West of Everything” and “A Life in School,” but she more or less retired after that — until now, re-emerging with another impassioned missive that concerns itself with shadows and dualities and the self. “Reading Through the Night” is a perfect book for anyone who believes literature should amount to more than diversion and fodder for term papers. The recent trend in better writing about reading generally falls into two camps: books that tell the story of a writer’s relationship with another writer, and books that chronicle one’s reading life. Tompkins does both.

Tompkins produced two fine books in the 1990s, “West of Everything” and “A Life in School,” but she more or less retired after that — until now, re-emerging with another impassioned missive that concerns itself with shadows and dualities and the self. “Reading Through the Night” is a perfect book for anyone who believes literature should amount to more than diversion and fodder for term papers. The recent trend in better writing about reading generally falls into two camps: books that tell the story of a writer’s relationship with another writer, and books that chronicle one’s reading life. Tompkins does both. In every argument, debate or article about the rise of the modern celebrity, one name always reappears:

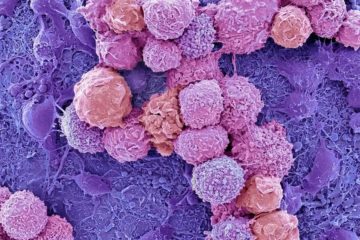

In every argument, debate or article about the rise of the modern celebrity, one name always reappears:  Balls of human brain cells grown in a dish, known as

Balls of human brain cells grown in a dish, known as  “Those in the 1 percent are walking off with the riches, but in doing so they have provided nothing but anxiety and insecurity to the 99 percent,” explained Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz in his 2012 book The Price of Inequality. The “main fault line in the American society is . . . between the 1 percent and everybody else,” insisted celebrated economists Emanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman in their book The Triumph of Injustice, published amid the 2020 presidential campaign. Dramatic wealth tax proposals by Democratic presidential candidates Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, chair of the tax-writing committee Senator Ron Wyden, and even an income taxation plan by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez do not come close to hiking taxes on anyone below the 1 percent threshold. The same is true of the suggestions by numerous tax academics considering how to tax the rich.

“Those in the 1 percent are walking off with the riches, but in doing so they have provided nothing but anxiety and insecurity to the 99 percent,” explained Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz in his 2012 book The Price of Inequality. The “main fault line in the American society is . . . between the 1 percent and everybody else,” insisted celebrated economists Emanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman in their book The Triumph of Injustice, published amid the 2020 presidential campaign. Dramatic wealth tax proposals by Democratic presidential candidates Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, chair of the tax-writing committee Senator Ron Wyden, and even an income taxation plan by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez do not come close to hiking taxes on anyone below the 1 percent threshold. The same is true of the suggestions by numerous tax academics considering how to tax the rich.