Category: Recommended Reading

Bringing The Illiad Into Arabic

Suleiman Al-Bustani at The Baffler:

UNTIL THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, The Iliad had only been translated into European languages. By 1914, however, the situation had changed. Suleiman Al-Bustani’s 1904 Arabic version was just one among many translations into non-European languages—Armenian, Bengali, Urdu, Turkish, Gujrati, and Marathi, among others. This sudden interest in an ancient Greek epic poem might be understood from an anti-colonial perspective. It reflects the belief, held by many intellectuals of the period, that the symbolic power of Homer could be used to resist European claims to authority in an era of imperial expansion. If Homer’s epic is born, as Bustani argues, of the four corners of the world, the principle so central to Western Europe’s “civilizing mission”—that the ideas of Ancient Greece are the cultural foundation of the Christian West—loses some legitimacy.

UNTIL THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, The Iliad had only been translated into European languages. By 1914, however, the situation had changed. Suleiman Al-Bustani’s 1904 Arabic version was just one among many translations into non-European languages—Armenian, Bengali, Urdu, Turkish, Gujrati, and Marathi, among others. This sudden interest in an ancient Greek epic poem might be understood from an anti-colonial perspective. It reflects the belief, held by many intellectuals of the period, that the symbolic power of Homer could be used to resist European claims to authority in an era of imperial expansion. If Homer’s epic is born, as Bustani argues, of the four corners of the world, the principle so central to Western Europe’s “civilizing mission”—that the ideas of Ancient Greece are the cultural foundation of the Christian West—loses some legitimacy.

These translations were also far more than responses to Europe. For Bustani, The Iliad represented an inquiry into the Jahiliya of the Greeks: the period in Greek history that corresponds to the period in Arab history marked by the absence of divine guidance, prior to the revelation of the Quran.

more here.

On George Balanchine’s Vienna Waltzes

Laura Jacobs at The New Criterion:

The map of Balanchine’s life once he left Russia in 1924 and until he finally settled into the New York City Ballet in 1948 may read as a kind of wandering, but his life as an artist was made of circles: the revolving of the repertory, the return to old ballets, the rethinking and recalibration of steps and phrases. To the dismay of his audience, for instance, Balanchine pared back the iconic Apollon musagète, his breakthrough of 1928. Again and again he rechoreographed Stravinsky’s Le Baiser de la fée (based on heartbroken melodies by Tchaikovsky), trying to find the right form for its story of a child kissed into art and thus frozen out of a normal life—his story. And despite the astonishing breadth of his repertory, it was dominated by what one might call the waltz step of desire–love–loss. In fact, this was a vortex Balanchine needed. The centrifugal pull of the waltz, its three-four time as self-generating as the tide, rolling and turning, drawing one in and under, was pure energy.

The map of Balanchine’s life once he left Russia in 1924 and until he finally settled into the New York City Ballet in 1948 may read as a kind of wandering, but his life as an artist was made of circles: the revolving of the repertory, the return to old ballets, the rethinking and recalibration of steps and phrases. To the dismay of his audience, for instance, Balanchine pared back the iconic Apollon musagète, his breakthrough of 1928. Again and again he rechoreographed Stravinsky’s Le Baiser de la fée (based on heartbroken melodies by Tchaikovsky), trying to find the right form for its story of a child kissed into art and thus frozen out of a normal life—his story. And despite the astonishing breadth of his repertory, it was dominated by what one might call the waltz step of desire–love–loss. In fact, this was a vortex Balanchine needed. The centrifugal pull of the waltz, its three-four time as self-generating as the tide, rolling and turning, drawing one in and under, was pure energy.

more here.

The fear and fury of these Florida parents

Caitlin Gibson in The Washington Post:

In a nearby community in central Florida, Barbara Mellen attended a recent open house at her son’s elementary school and asked her child’s teacher to suggest a few titles or authors that might help her second-grader develop more interest in reading. The teacher looked anxious, she says, and told her he couldn’t recommend any books.

In the Facebook group Brittany Minor created five years ago for Black mothers like herself in Orlando, discussions among the 2,800 members have reached new depths of frustration and fatigue. These moms are watching what is happening in Florida, the shifting of the political and cultural environment around them, “and they are tired, they feel helpless, they feel hopeless,” Minor says. “The common thread is that people feel broken.”

More here.

What Plants Are Saying About Us

Amanda Gefter in Nautilus:

I was never into house plants until I bought one on a whim—a prayer plant, it was called, a lush, leafy thing with painterly green spots and ribs of bright red veins. The night I brought it home I heard a rustling in my room. Had something scurried? A mouse? Three jumpy nights passed before I realized what was happening: The plant was moving. During the day, its leaves would splay flat, sunbathing, but at night they’d clamber over one another to stand at attention, their stems steadily rising as the leaves turned vertical, like hands in prayer.

I was never into house plants until I bought one on a whim—a prayer plant, it was called, a lush, leafy thing with painterly green spots and ribs of bright red veins. The night I brought it home I heard a rustling in my room. Had something scurried? A mouse? Three jumpy nights passed before I realized what was happening: The plant was moving. During the day, its leaves would splay flat, sunbathing, but at night they’d clamber over one another to stand at attention, their stems steadily rising as the leaves turned vertical, like hands in prayer.

“Who knew plants do stuff?” I marveled. Suddenly plants seemed more interesting. When the pandemic hit, I brought more of them home, just to add some life to the place, and then there were more, and more still, until the ratio of plants to household surfaces bordered on deranged. Bushwhacking through my apartment, I worried whether the plants were getting enough water, or too much water, or the right kind of light—or, in the case of a giant carnivorous pitcher plant hanging from the ceiling, whether I was leaving enough fish food in its traps. But what never occurred to me, not even once, was to wonder what the plants were thinking.

More here.

Wednesday, March 8, 2023

Robert Pinsky on “True Life,” a collection of verse by the Polish poet Adam Zagajewski

Robert Pinsky in the New York Times:

The Polish poet Adam Zagajewski’s great poem “To Go to Lvov” has a special importance for many young poets in different languages. That poem weaves the historical and the personal, the rhythms of cataclysm and of ordinary life, loss and persistence, all embodied in Zagajewski’s native city. “To Go to Lvov” has provided a model — intensely local, adamantly not nationalistic — for poems rooted in Philadelphia, Buenos Aires and Lahore.

The Polish poet Adam Zagajewski’s great poem “To Go to Lvov” has a special importance for many young poets in different languages. That poem weaves the historical and the personal, the rhythms of cataclysm and of ordinary life, loss and persistence, all embodied in Zagajewski’s native city. “To Go to Lvov” has provided a model — intensely local, adamantly not nationalistic — for poems rooted in Philadelphia, Buenos Aires and Lahore.

The Polish pronunciation and spelling Lvov has been replaced by the Ukrainian Lviv, and behind it the linguistic and cultural echoes of Lwow and Lemberg, in an involved, blood-determined pageant of related but different names for the place. That ongoing story makes Zagajewski’s poem of shared, discordant layers of loss and persistence feel all the more poignant, and the more urgently relevant, since the invasion of Ukraine by the Putin regime, with its war crimes against an entire population.

More here.

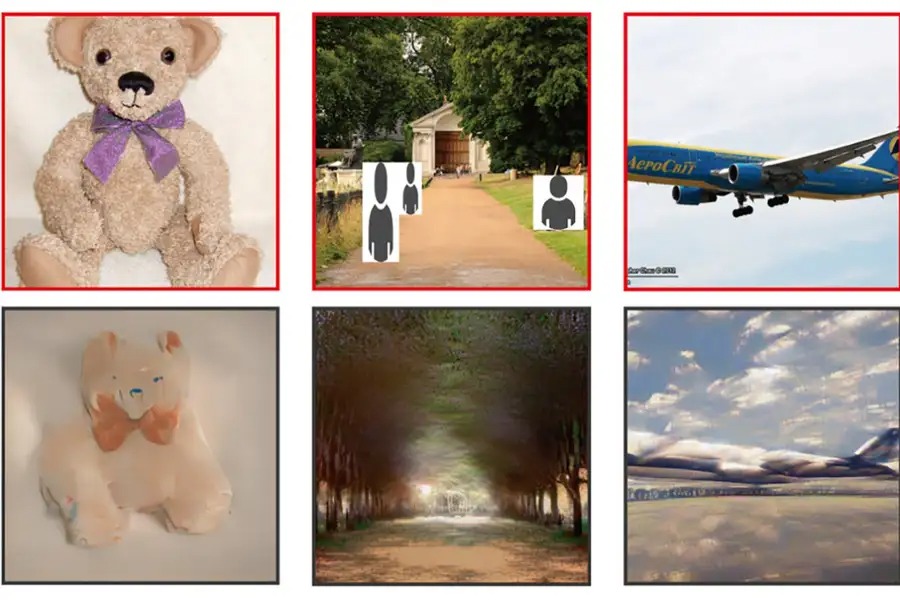

AI creates pictures of what people are seeing by analysing brain scans

Carissa Wong in New Scientist:

A tweak to a popular text-to-image-generating artificial intelligence allows it to turn brain signals directly into pictures. The system requires extensive training using bulky and costly imaging equipment, however, so everyday mind reading is a long way from reality.

Several research groups have previously generated images from brain signals using energy-intensive AI models that require fine-tuning of millions to billions of parameters.

Now, Shinji Nishimoto and Yu Takagi at Osaka University in Japan have developed a much simpler approach using Stable Diffusion, a text-to-image generator released by Stability AI in August 2022. Their new method involves thousands, rather than millions, of parameters.

More here.

GPT 5 is All About Data

The Evolution of Social Paradoxes

David Pinsof in PsyArXiv Preprints:

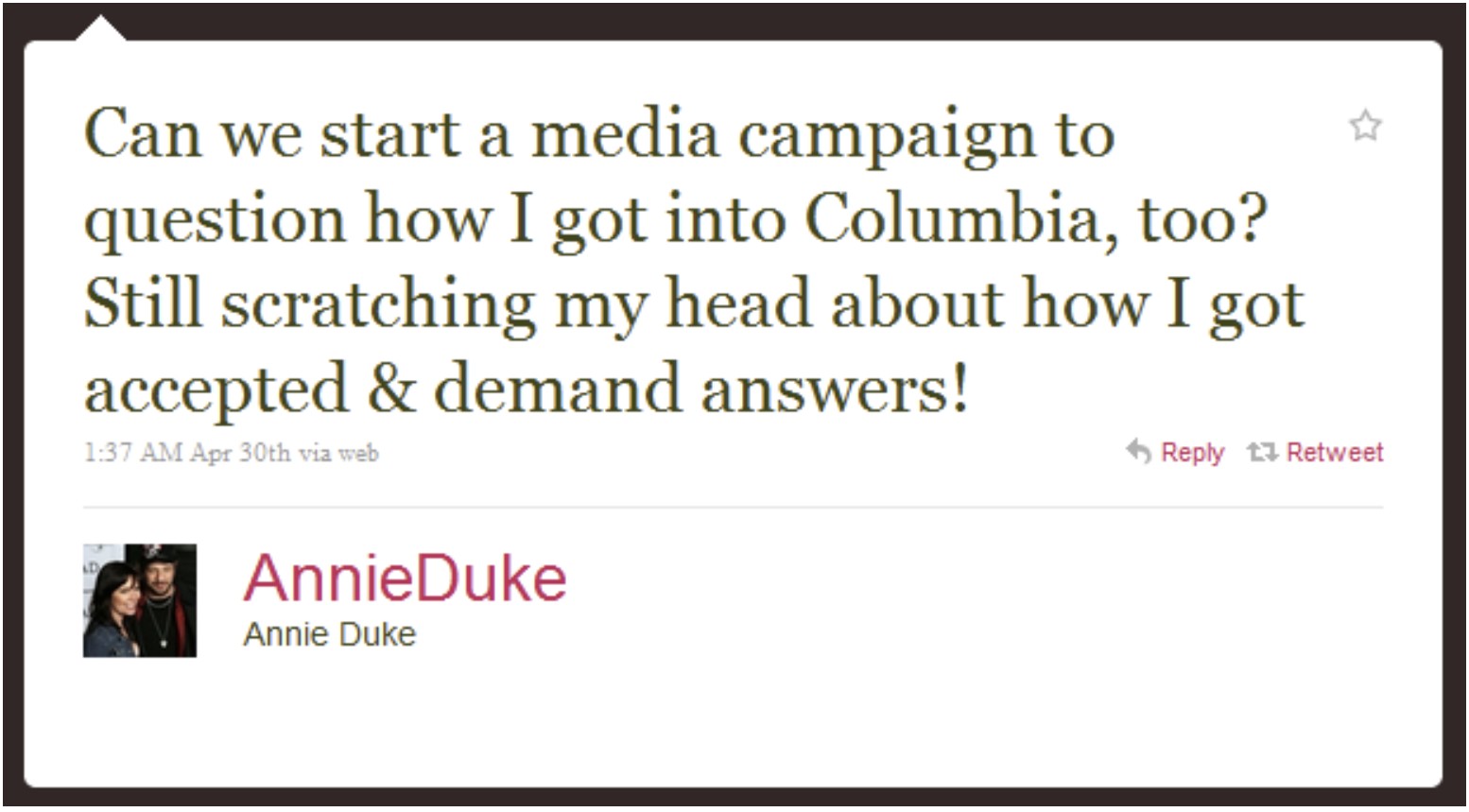

Human behavior is often paradoxical. We show humility to prove we’re better than other people, we bravely defy social norms so that people will praise us, and we donate to charity anonymously to get credit for not caring about getting credit. Here, I argue that these and other social paradoxes have a common thread: they are all attempts to signal a trait while concealing the fact that one is signaling the trait. Such self-negating signals emerge from the interaction of two cognitive abilities: 1) cue-based inference, and 2) recursive mentalizing. If agents can model each other’s mental states, including their intentions to signal positive traits, then intentional signals of positive traits can, themselves, become cues of negative traits. The result is that status-seeking and virtue-signaling are forced to occur covertly, without becoming common knowledge among signalers or recipients. Social paradoxes also play a crucial role in enabling intergroup dominance by inhibiting common knowledge of the group’s dominance-seeking tactics, which would otherwise disrupt coordination by eliciting moral disapproval. The analysis of social paradoxes can explain a variety of puzzling aspects of human social life, including the cultural evolution of status symbols, the function of sacred values, and the nature of political belief systems.

Human behavior is often paradoxical. We show humility to prove we’re better than other people, we bravely defy social norms so that people will praise us, and we donate to charity anonymously to get credit for not caring about getting credit. Here, I argue that these and other social paradoxes have a common thread: they are all attempts to signal a trait while concealing the fact that one is signaling the trait. Such self-negating signals emerge from the interaction of two cognitive abilities: 1) cue-based inference, and 2) recursive mentalizing. If agents can model each other’s mental states, including their intentions to signal positive traits, then intentional signals of positive traits can, themselves, become cues of negative traits. The result is that status-seeking and virtue-signaling are forced to occur covertly, without becoming common knowledge among signalers or recipients. Social paradoxes also play a crucial role in enabling intergroup dominance by inhibiting common knowledge of the group’s dominance-seeking tactics, which would otherwise disrupt coordination by eliciting moral disapproval. The analysis of social paradoxes can explain a variety of puzzling aspects of human social life, including the cultural evolution of status symbols, the function of sacred values, and the nature of political belief systems.

More here.

Achille Mbembe: “Negative Messianism in the Age of Animism”

The Beaded Masterpieces of Myrlande Constant

Jerry Saltz at New York Magazine:

The large masterpieces in the upper two rooms mushroom into psychological and spatial multitudes. Constant is working at the scale of the Mexican muralists while echoing something of Chris Ofili’s early dazzling dotted paintings with elephant dung attached. You look at Constant’s work all at once and also millimeter by millimeter, bead by bead. The maniacal density of visual information is transporting.

The large masterpieces in the upper two rooms mushroom into psychological and spatial multitudes. Constant is working at the scale of the Mexican muralists while echoing something of Chris Ofili’s early dazzling dotted paintings with elephant dung attached. You look at Constant’s work all at once and also millimeter by millimeter, bead by bead. The maniacal density of visual information is transporting.

The surfaces speak. The angle of a sequin can create an arching eyebrow, a sly smile, or a flaring nostril. Each bead has a different reflection depending on what angle it is attached to the surface. Things glimmer then come into focus: You make out craggy rocks, flowers in gardens, water flowing. Mythical scenes form as if spoken to life from some ancient oratory.

more here.

BTS: Permission to Desire

Rani Neutill at the LARB:

As a scholar, I decided to bring my devotion to BTS to my research. Because of my growing fascination with this segment of BTS fandom and their love for the group, I interviewed 25 Gen-X women of diverse backgrounds who currently reside in the United States. Older women face enormous stigma for loving a “boy band,” and the seven Korean men of BTS are wholly different from the men many of us were taught to idealize. Women my age are rarely given the space to express desire, let alone lust, and I wanted to understand the contours and contexts of their experience.

As a scholar, I decided to bring my devotion to BTS to my research. Because of my growing fascination with this segment of BTS fandom and their love for the group, I interviewed 25 Gen-X women of diverse backgrounds who currently reside in the United States. Older women face enormous stigma for loving a “boy band,” and the seven Korean men of BTS are wholly different from the men many of us were taught to idealize. Women my age are rarely given the space to express desire, let alone lust, and I wanted to understand the contours and contexts of their experience.

What I heard were stories about how BTS has alleviated the sorrows that came from living through the pandemic as stay-at-home moms, remote workers, or unemployed women — women who feel that, once they pass the age of 40, they are no longer allowed to have desires. I found that BTS has been a catalyst for a collective reckoning among many Gen-X women about how the objects of their desires have been shaped by the media and how the freedom to desire has been foreclosed by age.

more here.

Wednesday Poem

A. Machine

Of heaven, under the overpass and passed over,

The past is over and I’m over the past. My odometer

Is broken, can you help me? When you get this mess-

Age, I may be a half-ton crush, a half tone of mist

And mystery, maybe trooper bait with the ambulance

Ambling somewhere, or a dial of holy stations, a band-

Age of clamor and spooling, a dash and semaphore,

A pupil of motion on my way to be buried or planted or

Crammed or creamed, treading light and water or tread

and trepidation, maybe. Hey, I am backfiring along a road

Through the future, I am alive skidding on the tongue,

When you get this message, will you sigh, My lover is gone?

by Terrance Hayes

from The Academy of American Poets

The Patriarchs – the roots of male domination

Alex von Tunzelmann in The Guardian:

Are men and women naturally different, and do the roles socially assigned to us proceed from those differences? Refreshingly, science journalist and broadcaster Angela Saini begins her stirring interrogation of patriarchy by arguing that it is neither constant, inevitable nor unshakeable. “By thinking about gendered inequality as rooted in something unalterable within us, we fail to see it for what it is,” she writes, “something more fragile that has had to be constantly remade and reasserted.”

Are men and women naturally different, and do the roles socially assigned to us proceed from those differences? Refreshingly, science journalist and broadcaster Angela Saini begins her stirring interrogation of patriarchy by arguing that it is neither constant, inevitable nor unshakeable. “By thinking about gendered inequality as rooted in something unalterable within us, we fail to see it for what it is,” she writes, “something more fragile that has had to be constantly remade and reasserted.”

Anthropologists, political theorists, feminists and, importantly, patriarchs themselves have often reached across time and space to look for the origins of sex and gender division. In 1680, Sir Robert Filmer’s Patriarcha invoked ancient and biblical authorities as evidence that patriarchy (with the divine right of kings at its head) was natural and ordered by God. Even when later revolutionaries rejected the idea of a king as the head of a nation-family, they were reluctant to let go of elite male power. Thomas Jefferson wrote, creepily, that “the tender breasts of ladies were not formed for political convulsion”.

Friedrich Engels broke with this narrative when he claimed that the transition from ancient matriarchies to patriarchy represented “the world historical defeat of the female sex” – a calamity that reduced women to the status of property.

More here.

How the first chatbot predicted the dangers of AI more than 50 years ago

Oshan Jarow in Vox:

It didn’t take long for Microsoft’s new AI-infused search engine chatbot — codenamed “Sydney” — to display a growing list of discomforting behaviors after it was introduced early in February, with weird outbursts ranging from unrequited declarations of love to painting some users as “enemies.”

It didn’t take long for Microsoft’s new AI-infused search engine chatbot — codenamed “Sydney” — to display a growing list of discomforting behaviors after it was introduced early in February, with weird outbursts ranging from unrequited declarations of love to painting some users as “enemies.”

As human-like as some of those exchanges appeared, they probably weren’t the early stirrings of a conscious machine rattling its cage. Instead, Sydney’s outbursts reflect its programming, absorbing huge quantities of digitized language and parroting back what its users ask for. Which is to say, it reflects our online selves back to us. And that shouldn’t have been surprising — chatbots’ habit of mirroring us back to ourselves goes back way further than Sydney’s rumination on whether there is a meaning to being a Bing search engine. In fact, it’s been there since the introduction of the first notable chatbot almost 50 years ago.

In 1966, MIT computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum released ELIZA (named after the fictional Eliza Doolittle from George Bernard Shaw’s 1913 play Pygmalion), the first program that allowed some kind of plausible conversation between humans and machines. The process was simple: Modeled after the Rogerian style of psychotherapy, ELIZA would rephrase whatever speech input it was given in the form of a question. If you told it a conversation with your friend left you angry, it might ask, “Why do you feel angry?”

More here.

Tuesday, March 7, 2023

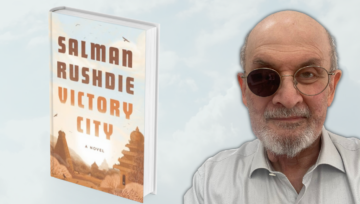

Salman Rushdie’s new novel is a powerful reminder of his vital role in the endless battle for free speech

Christian Kriticos in Quillette:

Salman Rushdie found his voice in 1975. His first novel, Grimus, published earlier that year, had been ignored by the public and derided by the critics. At the same time, Rushdie was watching younger contemporaries such as Ian McEwan and Martin Amis cement their places among the British literary elite, while he remained saddled with his day job as an advertising copywriter.

Salman Rushdie found his voice in 1975. His first novel, Grimus, published earlier that year, had been ignored by the public and derided by the critics. At the same time, Rushdie was watching younger contemporaries such as Ian McEwan and Martin Amis cement their places among the British literary elite, while he remained saddled with his day job as an advertising copywriter.

Despite these setbacks, Rushdie still felt that he had a fresh, authentic literary voice to discover. He travelled back to his native India in search of it, knowing only that he wanted “to write a novel of childhood.” It was on this trip that he began to conceive Midnight’s Children, a novel he would write against the tradition of British literature set in India. While he admired some of these classic works, such as E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India, he took issue with the voice. The British style was cool and collected. The India that Rushdie knew was anything but. It was hot and “noisy and vulgar and crowded and sensual.” And it needed a voice to reflect that.

It was this unique migrant’s voice that catapulted Rushdie to literary stardom. His narrator in Midnight’s Children was loud and frenetic, reflecting not only the energy of a post-independence India, but also the magic-realist style that would become a trademark of his fiction.

More here.

Scott Aaronson: Why am I not terrified of AI?

Scott Aaronson in Shtetl-Optimized:

Given the new reality, and my full acknowledgment of the new reality, and my refusal to go down with the sinking ship of “AI will probably never do X and please stop being so impressed that it just did X”—many have wondered, why aren’t I much more terrified? Why am I still not fully on board with the Orthodox AI doom scenario, the Eliezer Yudkowsky one, the one where an unaligned AI will sooner or later (probably sooner) unleash self-replicating nanobots that turn us all to goo?

Given the new reality, and my full acknowledgment of the new reality, and my refusal to go down with the sinking ship of “AI will probably never do X and please stop being so impressed that it just did X”—many have wondered, why aren’t I much more terrified? Why am I still not fully on board with the Orthodox AI doom scenario, the Eliezer Yudkowsky one, the one where an unaligned AI will sooner or later (probably sooner) unleash self-replicating nanobots that turn us all to goo?

Is the answer simply that I’m too much of an academic conformist, afraid to endorse anything that sounds weird or far-out or culty? I certainly should consider the possibility. If so, though, how do you explain the fact that I’ve publicly said things, right on this blog, several orders of magnitude likelier to get me in trouble than “I’m scared about AI destroying the world”—an idea now so firmly within the Overton Window that Henry Kissinger gravely ponders it in the Wall Street Journal?

More here. And see Scott Alexander’s reply to Scott Aaronson here.

John Carmack: The code for AGI will be simple

The World Speculation Made

Aris Komporozos-Athanasiou in the Boston Review:

Speculation encompasses a duality at the core of all financial activity. When pushed to its outermost limit, it can unleash formidable destructive forces and lead to the burst of market bubbles, such as seventeenth-century Amsterdam’s notorious tulip craze, the Victorian era’s railway manias, last century’s Great Depression, or the more recent 2008 global financial crisis. During these periods, market “passions” take hold: traders venerate ethereal values with no material referents or links to “fundamentals.” Yet speculation is also the market’s indispensable lubricant. All speculative trades calibrate risks to generate yields and prevent markets from “overheating.”

Speculation encompasses a duality at the core of all financial activity. When pushed to its outermost limit, it can unleash formidable destructive forces and lead to the burst of market bubbles, such as seventeenth-century Amsterdam’s notorious tulip craze, the Victorian era’s railway manias, last century’s Great Depression, or the more recent 2008 global financial crisis. During these periods, market “passions” take hold: traders venerate ethereal values with no material referents or links to “fundamentals.” Yet speculation is also the market’s indispensable lubricant. All speculative trades calibrate risks to generate yields and prevent markets from “overheating.”

More here.

One afternoon a few weeks ago, Alicea Hotchkiss’s 14-year-old son, Eli, came home from his high school in Tampa with a question about something a classmate had said to him. He’d heard the student use the word “gay” as an insult, so Eli responded the way he always does when this happens. “Hey,” Eli said, “my dad’s gay.” But this time, Eli told his mom, the other kid offered a startling rebuke: You’re not allowed to say that at school.

One afternoon a few weeks ago, Alicea Hotchkiss’s 14-year-old son, Eli, came home from his high school in Tampa with a question about something a classmate had said to him. He’d heard the student use the word “gay” as an insult, so Eli responded the way he always does when this happens. “Hey,” Eli said, “my dad’s gay.” But this time, Eli told his mom, the other kid offered a startling rebuke: You’re not allowed to say that at school.