Anne Fadiman at Harper’s Magazine:

Until last summer, we had a dead frog in our freezer. When Bunky died, George and I thought we should wait to bury him till both our grown children were home, so we put him in a Ziploc bag and propped him on his side on a shallow shelf in the freezer door, just above the icemaker. Bunky was flat and compact and, very soon, as rigid as a cell phone. He fit perfectly. I’d always wondered what KitchenAid intended that shelf for—it was too narrow for any food I could think of—but now we knew. It was intended to hold a frog.

Until last summer, we had a dead frog in our freezer. When Bunky died, George and I thought we should wait to bury him till both our grown children were home, so we put him in a Ziploc bag and propped him on his side on a shallow shelf in the freezer door, just above the icemaker. Bunky was flat and compact and, very soon, as rigid as a cell phone. He fit perfectly. I’d always wondered what KitchenAid intended that shelf for—it was too narrow for any food I could think of—but now we knew. It was intended to hold a frog.

There are two kinds of pets—the ones you choose and the ones that happen to you. Bunky belonged to the second category. He entered our family in the haphazard fashion of pets of that ilk: tadpole kit (cubical plastic “habitat” with domed top, like nave of Hagia Sophia, sans tadpole but accompanied by redeemable coupon), left by educational-toy-oriented grandmother for granddaughter under Christmas tree; kit sidelined for years on toy shelf; kit discovered by granddaughter’s preschool-age little brother; tadpole coveted; tadpole coupon redeemed by parents; tadpole shipped to New York City from Florida in Styrofoam container; tadpole universally admired for transparent skin (visibly beating heart!) and awesome metamorphosis (weird whiskers! hind legs! front legs! no more tail!); froglet admired somewhat less; adult frog mostly ignored, except by visiting small boys, who, if they didn’t have frogs themselves, paused to pay brief homage before moving on to Legos, and by owner’s father, who, despite initial intentions to teach son responsibility through pet care, ended up feeding frog (Stage Two Food Nuggets, meted out with tiny yellow Stage Two Food Serving Spoon dainty enough for fairy) and, once frog graduated from Hagia Sophia, cleaning aquarium, first two-gallon plastic, then four-gallon glass (challenging, because frog, coated with gelatinous goo, required apprehension and temporary relocation while aquarium was emptied, refilled, and doctored with dechlorinating crystals, and damn, was he slippery).

more here.

On Saturday 13 December 1958, the People’s Republic of China declared war on a bird. Mobilisation was total: 600 million enlisted for the fight. Their target was a tiny songbird, between five and six inches long: the Eurasian tree sparrow. It might seem like overkill, writes Stephen Moss in his history of human-avian relations, but in the eyes of China’s leaders the sparrows more than deserved it. An estimated 1.5m tonnes of grain disappeared down the gullets of said feathered gourmets each year. China was short on food – and short on patience. Peace was never an option.

On Saturday 13 December 1958, the People’s Republic of China declared war on a bird. Mobilisation was total: 600 million enlisted for the fight. Their target was a tiny songbird, between five and six inches long: the Eurasian tree sparrow. It might seem like overkill, writes Stephen Moss in his history of human-avian relations, but in the eyes of China’s leaders the sparrows more than deserved it. An estimated 1.5m tonnes of grain disappeared down the gullets of said feathered gourmets each year. China was short on food – and short on patience. Peace was never an option.

“

“ Tompkins produced two fine books in the 1990s, “West of Everything” and “A Life in School,” but she more or less retired after that — until now, re-emerging with another impassioned missive that concerns itself with shadows and dualities and the self. “Reading Through the Night” is a perfect book for anyone who believes literature should amount to more than diversion and fodder for term papers. The recent trend in better writing about reading generally falls into two camps: books that tell the story of a writer’s relationship with another writer, and books that chronicle one’s reading life. Tompkins does both.

Tompkins produced two fine books in the 1990s, “West of Everything” and “A Life in School,” but she more or less retired after that — until now, re-emerging with another impassioned missive that concerns itself with shadows and dualities and the self. “Reading Through the Night” is a perfect book for anyone who believes literature should amount to more than diversion and fodder for term papers. The recent trend in better writing about reading generally falls into two camps: books that tell the story of a writer’s relationship with another writer, and books that chronicle one’s reading life. Tompkins does both. In every argument, debate or article about the rise of the modern celebrity, one name always reappears:

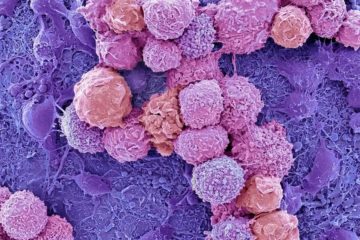

In every argument, debate or article about the rise of the modern celebrity, one name always reappears:  Balls of human brain cells grown in a dish, known as

Balls of human brain cells grown in a dish, known as  “Those in the 1 percent are walking off with the riches, but in doing so they have provided nothing but anxiety and insecurity to the 99 percent,” explained Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz in his 2012 book The Price of Inequality. The “main fault line in the American society is . . . between the 1 percent and everybody else,” insisted celebrated economists Emanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman in their book The Triumph of Injustice, published amid the 2020 presidential campaign. Dramatic wealth tax proposals by Democratic presidential candidates Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, chair of the tax-writing committee Senator Ron Wyden, and even an income taxation plan by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez do not come close to hiking taxes on anyone below the 1 percent threshold. The same is true of the suggestions by numerous tax academics considering how to tax the rich.

“Those in the 1 percent are walking off with the riches, but in doing so they have provided nothing but anxiety and insecurity to the 99 percent,” explained Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz in his 2012 book The Price of Inequality. The “main fault line in the American society is . . . between the 1 percent and everybody else,” insisted celebrated economists Emanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman in their book The Triumph of Injustice, published amid the 2020 presidential campaign. Dramatic wealth tax proposals by Democratic presidential candidates Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, chair of the tax-writing committee Senator Ron Wyden, and even an income taxation plan by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez do not come close to hiking taxes on anyone below the 1 percent threshold. The same is true of the suggestions by numerous tax academics considering how to tax the rich. Until last summer, we had a dead frog in our freezer. When Bunky died, George and I thought we should wait to bury him till both our grown children were home, so we put him in a Ziploc bag and propped him on his side on a shallow shelf in the freezer door, just above the icemaker. Bunky was flat and compact and, very soon, as rigid as a cell phone. He fit perfectly. I’d always wondered what KitchenAid intended that shelf for—it was too narrow for any food I could think of—but now we knew. It was intended to hold a frog.

Until last summer, we had a dead frog in our freezer. When Bunky died, George and I thought we should wait to bury him till both our grown children were home, so we put him in a Ziploc bag and propped him on his side on a shallow shelf in the freezer door, just above the icemaker. Bunky was flat and compact and, very soon, as rigid as a cell phone. He fit perfectly. I’d always wondered what KitchenAid intended that shelf for—it was too narrow for any food I could think of—but now we knew. It was intended to hold a frog. Their fondness for animals. A multistory pet shop: canaries on the second floor, great apes at the top. A couple of years ago, a man was arrested on Fifth Avenue for driving a giraffe around in his truck. He explained that his giraffe didn’t get enough air out in the suburbs where he kept it and that he’d found this to be a good way to get it some air. In Central Park, a lady brought a gazelle to graze. To the court, she explained that the gazelle was a person. “Yet it doesn’t speak,” the judge said. “Oh, yes, it speaks the language of lovingkindness.” Five-dollar fine. There’s also the three-kilometer tunnel under the Hudson and the impressive bridge to New Jersey.

Their fondness for animals. A multistory pet shop: canaries on the second floor, great apes at the top. A couple of years ago, a man was arrested on Fifth Avenue for driving a giraffe around in his truck. He explained that his giraffe didn’t get enough air out in the suburbs where he kept it and that he’d found this to be a good way to get it some air. In Central Park, a lady brought a gazelle to graze. To the court, she explained that the gazelle was a person. “Yet it doesn’t speak,” the judge said. “Oh, yes, it speaks the language of lovingkindness.” Five-dollar fine. There’s also the three-kilometer tunnel under the Hudson and the impressive bridge to New Jersey. Stephanie Blendermann, 65, had good reason to worry about heart disease. Three of her sisters died in their 40s or early 50s from heart attacks, and her father needed surgery to bypass clogged arteries. She also suffered from an autoimmune disorder that results in chronic inflammation and boosts the odds of developing cardiovascular illnesses. “I have an interesting medical chart,” says Blendermann, a real estate agent in Prior Lake, Minnesota.

Stephanie Blendermann, 65, had good reason to worry about heart disease. Three of her sisters died in their 40s or early 50s from heart attacks, and her father needed surgery to bypass clogged arteries. She also suffered from an autoimmune disorder that results in chronic inflammation and boosts the odds of developing cardiovascular illnesses. “I have an interesting medical chart,” says Blendermann, a real estate agent in Prior Lake, Minnesota. What is synthetic biology and what are scientists trying to do with it? Simply put, we could say that synthetic biology is a fusion of biology, especially molecular biology, and engineering. The distinctive thing about it is that it treats cells as programmable devices. It’s a kind of tinker toy approach that builds circuits, but not out of wires and switches like we’re used to, but rather out of biological components, like proteins and genes. Programming cells in this way isn’t really all that different from programming computers, except that the programming language isn’t Python, or C++. It’s the language of biology, the language of DNA, with the goal of making proteins that will interact with each other in some clever ways.

What is synthetic biology and what are scientists trying to do with it? Simply put, we could say that synthetic biology is a fusion of biology, especially molecular biology, and engineering. The distinctive thing about it is that it treats cells as programmable devices. It’s a kind of tinker toy approach that builds circuits, but not out of wires and switches like we’re used to, but rather out of biological components, like proteins and genes. Programming cells in this way isn’t really all that different from programming computers, except that the programming language isn’t Python, or C++. It’s the language of biology, the language of DNA, with the goal of making proteins that will interact with each other in some clever ways. T

T Twenty-five years on from the YBA movement, Lucas is still admired for her lightness of touch. She used sex to draw people in to her work, she recently said – to keep art open to “plebs like myself”. She was funny, but she was funny because she was clever: much of her work was barely “made”, just a couple of objects, perfectly arranged. Has she never wanted assistants, like Hirst, to help her churn out more bunnies? “If I can’t be bothered to make ’em, I wouldn’t want someone else to make ’em,” she says. “And I don’t know where I’m going with it until I’ve done it, so it’s not like I can tell someone else how to do it.” Unlike her former friend Tracey Emin, she does not try to draw.

Twenty-five years on from the YBA movement, Lucas is still admired for her lightness of touch. She used sex to draw people in to her work, she recently said – to keep art open to “plebs like myself”. She was funny, but she was funny because she was clever: much of her work was barely “made”, just a couple of objects, perfectly arranged. Has she never wanted assistants, like Hirst, to help her churn out more bunnies? “If I can’t be bothered to make ’em, I wouldn’t want someone else to make ’em,” she says. “And I don’t know where I’m going with it until I’ve done it, so it’s not like I can tell someone else how to do it.” Unlike her former friend Tracey Emin, she does not try to draw. Kazuo Ishiguro has had a busy few months. The acclaimed novelist has been attending film festivals and walking red carpets to promote the film Living, for which he wrote the screenplay. Living—a remake of the 1952 Japanese film Ikiru, directed by Akira Kurosawa, which was inspired by Leo Tolstoy’s 1886 novella

Kazuo Ishiguro has had a busy few months. The acclaimed novelist has been attending film festivals and walking red carpets to promote the film Living, for which he wrote the screenplay. Living—a remake of the 1952 Japanese film Ikiru, directed by Akira Kurosawa, which was inspired by Leo Tolstoy’s 1886 novella  In 2022, the

In 2022, the