Michael Clune at the Paris Review:

I’ve been clean for over twenty years. Let me give you an example of the kind of problem addiction is, the scale of the thing. In April 2019 I went to the dentist. I had a mild ache in a molar. He said the whole tooth was totally rotted all the way through, that they couldn’t do anything more with it. It was hopeless. The tooth was a total piece of shit and would have to be extracted. He gave me the number of a dental surgeon and I called and made an appointment. I talked to my dad, who’d had many teeth extracted, and he told me it was no big deal. When I got to the dental surgeon’s office I told him that I’m a recovering addict, and that I wanted to avoid opiate painkillers. He looked in my mouth and when he got out he said, “You’re going to need opiate painkillers.”

I’ve been clean for over twenty years. Let me give you an example of the kind of problem addiction is, the scale of the thing. In April 2019 I went to the dentist. I had a mild ache in a molar. He said the whole tooth was totally rotted all the way through, that they couldn’t do anything more with it. It was hopeless. The tooth was a total piece of shit and would have to be extracted. He gave me the number of a dental surgeon and I called and made an appointment. I talked to my dad, who’d had many teeth extracted, and he told me it was no big deal. When I got to the dental surgeon’s office I told him that I’m a recovering addict, and that I wanted to avoid opiate painkillers. He looked in my mouth and when he got out he said, “You’re going to need opiate painkillers.”

Then he shot me up with Novocain and he went in there with a wrench, and I realized that dentists have soft, delicate hands and seem like doctors, like intellectuals, but when you really need dental care, you go to a dental surgeon and their main qualification is brute physical strength.

more here.

For all mankind’s meddling, nature is obdurate. It didn’t stop evolving just because humans tried to keep it out. Wilson asks us to imagine our cities from the perspective of certain plants or animals. If you’re a seaside goldenrod or a strip of Danish scurvy grass, then the sodium-enriched verges created by winter salt trucks are a dream habitat. For a peregrine falcon, the difference between a twenty-storey skyscraper and a hundred-foot cliff is minimal: the dive-bombing potential is equally great. Nonetheless, not all natural species can adapt. As Wilson admits, our cities as they currently stand are the ‘site of eco-apocalypse’. Even putting the rights of nature aside, wilding our streets is in our self-interest. Just ask a psychologist or a physician. We’re happier, healthier and safer with nature near at hand.

For all mankind’s meddling, nature is obdurate. It didn’t stop evolving just because humans tried to keep it out. Wilson asks us to imagine our cities from the perspective of certain plants or animals. If you’re a seaside goldenrod or a strip of Danish scurvy grass, then the sodium-enriched verges created by winter salt trucks are a dream habitat. For a peregrine falcon, the difference between a twenty-storey skyscraper and a hundred-foot cliff is minimal: the dive-bombing potential is equally great. Nonetheless, not all natural species can adapt. As Wilson admits, our cities as they currently stand are the ‘site of eco-apocalypse’. Even putting the rights of nature aside, wilding our streets is in our self-interest. Just ask a psychologist or a physician. We’re happier, healthier and safer with nature near at hand. In 1696, Damaris Cudworth Masham, an Englishwoman and a reluctant philosopher, stepped from obscurity to publish a book whose title – A Discourse Concerning the Love of God – concealed the feminist gems within. For instance, she insisted, contrary to some philosophers and theologians of her day, that mothers were not corrupting forces but foundational to the pursuit of knowledge. Then in 1705 she entered the public sphere again with another work, more radical than the first, titled Occasional Thoughts in Reference to a Vertuous or Christian Life, in which she argued that women should contribute to all intellectual subjects: ‘I see no Reason why it should not be thought that all Science lyes as open to a Lady as to

In 1696, Damaris Cudworth Masham, an Englishwoman and a reluctant philosopher, stepped from obscurity to publish a book whose title – A Discourse Concerning the Love of God – concealed the feminist gems within. For instance, she insisted, contrary to some philosophers and theologians of her day, that mothers were not corrupting forces but foundational to the pursuit of knowledge. Then in 1705 she entered the public sphere again with another work, more radical than the first, titled Occasional Thoughts in Reference to a Vertuous or Christian Life, in which she argued that women should contribute to all intellectual subjects: ‘I see no Reason why it should not be thought that all Science lyes as open to a Lady as to  Millions of Americans who are at high risk for heart attacks and whose LDL cholesterol levels are disturbingly high have been told over and over again by their doctors to take a statin. These cheap generic drugs have been shown repeatedly to slash cholesterol levels and prevent heart attacks, strokes and deaths. But many people cannot or will not take the drugs, often reporting that statins make their muscles ache.

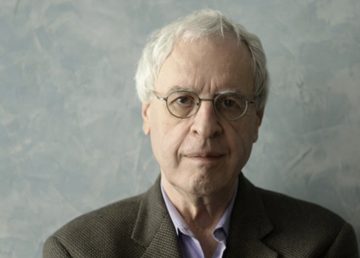

Millions of Americans who are at high risk for heart attacks and whose LDL cholesterol levels are disturbingly high have been told over and over again by their doctors to take a statin. These cheap generic drugs have been shown repeatedly to slash cholesterol levels and prevent heart attacks, strokes and deaths. But many people cannot or will not take the drugs, often reporting that statins make their muscles ache. In memory we are standing in the kitchen of the Treman Cottage at Breadloaf. It is late afternoon in the summer of 1976 and I have brought my copies of Return to a Place Lit by a Glass of Milk and Dismantling the Silence for Charles Simic to sign. He is slouching a bit, leaning against the counter, and seems genuinely touched that I had carried the books, deeply penciled and dog-eared, all the way from home.

In memory we are standing in the kitchen of the Treman Cottage at Breadloaf. It is late afternoon in the summer of 1976 and I have brought my copies of Return to a Place Lit by a Glass of Milk and Dismantling the Silence for Charles Simic to sign. He is slouching a bit, leaning against the counter, and seems genuinely touched that I had carried the books, deeply penciled and dog-eared, all the way from home. Painters have long struggled with the difficulties of depicting shadows, so much so that shadows — after a brief, spectacular showcase in ancient Roman paintings and mosaics — are almost absent from pictorial art up to the Renaissance and then are hardly present outside traditional Western art.

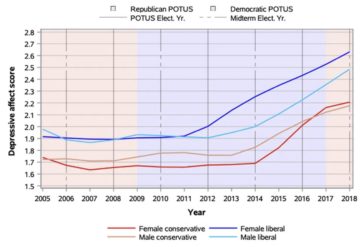

Painters have long struggled with the difficulties of depicting shadows, so much so that shadows — after a brief, spectacular showcase in ancient Roman paintings and mosaics — are almost absent from pictorial art up to the Renaissance and then are hardly present outside traditional Western art. Earlier this month the CDC released the results of its Youth Risk Behavior Survey of American teenagers. The findings have been much discussed, with the focus largely and understandably on the fact that

Earlier this month the CDC released the results of its Youth Risk Behavior Survey of American teenagers. The findings have been much discussed, with the focus largely and understandably on the fact that  I

I To get the inside story behind the chatbot—how it was made, how OpenAI has been updating it since release, and how its makers feel about its success—I talked to four people who helped build what has become

To get the inside story behind the chatbot—how it was made, how OpenAI has been updating it since release, and how its makers feel about its success—I talked to four people who helped build what has become  In this week’s New Yorker, the contributing writer Merve Emre

In this week’s New Yorker, the contributing writer Merve Emre  Devaka Gunawardena , Niyanthini Kadirgamar, and Ahilan Kadirgamar in Phenomenal World:

Devaka Gunawardena , Niyanthini Kadirgamar, and Ahilan Kadirgamar in Phenomenal World: Perry Anderson in New Left Review:

Perry Anderson in New Left Review: Kenda Mutongi in Boston Review:

Kenda Mutongi in Boston Review: Dylan Saba in Jewish Currents:

Dylan Saba in Jewish Currents: W

W