Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Robert Grosvenor (1937 – 2025) Sculptor

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Smoker

Ottessa Moshfegh in The Paris Review:

This one time, my dad bought me a house in Providence, Rhode Island. It was a two-story fake Colonial with yellow aluminum siding on Hawkins Street. We bought it from the bank for $55,000; it was one of many properties under foreclosure in the city in 2009. Dad and I had spent a few days driving around and looking at these houses. In one driveway, I found a dirty playing card depicting the biggest penis I could ever imagine—I still have it. In one basement, the realtor had to disclose, the former owner had tied his girlfriend’s lover to a chair, tortured him, and then shot him in the head.

This one time, my dad bought me a house in Providence, Rhode Island. It was a two-story fake Colonial with yellow aluminum siding on Hawkins Street. We bought it from the bank for $55,000; it was one of many properties under foreclosure in the city in 2009. Dad and I had spent a few days driving around and looking at these houses. In one driveway, I found a dirty playing card depicting the biggest penis I could ever imagine—I still have it. In one basement, the realtor had to disclose, the former owner had tied his girlfriend’s lover to a chair, tortured him, and then shot him in the head.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Trump Is Shutting Down the War On Cancer

Jonathan Mahler in The New York Times:

When America declared war on cancer more than 50 years ago, there was a misguided assumption outside the scientific community that it would be only a matter of years before the disease was eradicated — that defeating cancer would be no different than building an atomic bomb or putting a man on the moon. But there would be no miracle cure: As of this writing, some 40 percent of Americans will be diagnosed with cancer at some point in their life.

What there would be, however, was decades of minor breakthroughs that would accrue over time, transforming both our understanding of the disease and our ability to treat it. One way to measure the cumulative effect of those breakthroughs is with statistics: In the mid-1970s, America’s five-year cancer-survival rate sat at 49 percent; today, it is 68 percent. You can also correlate America’s sustained investment in cancer research directly with these returns: According to a recent study in The Journal of Clinical Oncology, every $326 that our government spends researching cancer extends a human life by one year. Now an extraordinarily successful scientific research system — one that took decades to build, has saved millions of lives and generated billions of dollars in profits for American companies and investors — is being dismantled before our eyes.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday Poem

White Corn Boy*

I am the White Corn Boy.

I walk in sight of my home.

I walk in plain sight of my home.

I walk in the straight path which is towards my home.

I walk to the entrance of my home.

I arrive at the beautiful goods curtain which hangs at the doorway.

I arrive at the entrance of my home.

I am in the middle of my home.

I am at the back of my home.

I am on top of the pollen footprint.

I am on top of the pollen seed print.

I am like the Most High Power Whose Ways Are Beautiful.

Before me it is beautiful,

Behind me it is beautiful,

Under me it is beautiful,

Above me it is beautiful,

All around me it is beautiful,

* From Aileen O’Brian, The Diné:

Origin Myths of the Navaho Indians.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday, September 12, 2025

Mark Blyth on Writing, Thinking, and Why AI Can’t Save You

Catherine E. De Vries at Etched in Marble:

Mark Blyth is not the kind of academic who waits to be summoned. His sharp insights, delivered in a no-nonsense Scottish accent, are difficult to ignore. He writes to provoke, to clarify, and, perhaps above all, to care. A professor of International Political Economy at Brown University, Blyth has built a career dismantling bad economic ideas.

In Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea, Angrynomics, and most recently Inflation: A Guide for Users and Losers (with Nicolò Fraccaroli), he has taken apart technocratic orthodoxies and asked the more difficult questions, about power, inequality, and the terms by which society is organized.

In my conversation with Blyth for Etched in Marble, his writing reveals itself not merely as a craft, but as a mode of resistance, a way of thinking aloud and, more crucially, against the grain. For Blyth, the page isn’t a place to polish conclusions, it’s where the real argument begins.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

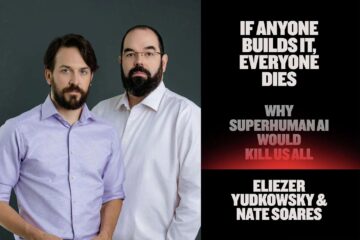

Scott Alexander reviews “If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies”

Scott Alexander at Astral Codex Ten:

Most people in AI safety (including me) are uncertain and confused and looking for least-bad incremental solutions. We think AI will probably be an exciting and transformative technology, but there’s some chance, 5 or 15 or 30 percent, that it might turn against humanity in a catastrophic way. Or, if it doesn’t, that there will be something less catastrophic but still bad – maybe humanity gradually fading into the background, the same way kings and nobles faded into the background during the modern era. This is scary, but AI is coming whether we like it or not, and probably there are also potential risks from delaying too hard. We’re not sure exactly what to do, but for now we want to build a firm foundation for reacting to any future threat. That means keeping AI companies honest and transparent, helping responsible companies like Anthropic stay in the race, and investing in understanding AI goal structures and the ways that AIs interpret our commands. Then at some point in the future, we’ll be close enough to the actually-scary AI that we can understand the threat model more clearly, get more popular buy-in, and decide what to do next.

Most people in AI safety (including me) are uncertain and confused and looking for least-bad incremental solutions. We think AI will probably be an exciting and transformative technology, but there’s some chance, 5 or 15 or 30 percent, that it might turn against humanity in a catastrophic way. Or, if it doesn’t, that there will be something less catastrophic but still bad – maybe humanity gradually fading into the background, the same way kings and nobles faded into the background during the modern era. This is scary, but AI is coming whether we like it or not, and probably there are also potential risks from delaying too hard. We’re not sure exactly what to do, but for now we want to build a firm foundation for reacting to any future threat. That means keeping AI companies honest and transparent, helping responsible companies like Anthropic stay in the race, and investing in understanding AI goal structures and the ways that AIs interpret our commands. Then at some point in the future, we’ll be close enough to the actually-scary AI that we can understand the threat model more clearly, get more popular buy-in, and decide what to do next.

MIRI thinks this is pathetic – like trying to protect against an asteroid impact by wearing a hard hat.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Do you know how escalators really work?

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

America, where everything gets dialed up to 11

Corey Robin at his own website:

We can’t just have a country where people, being people, get mad and rowdy every once in a while and shout at or beat each other up. No, we have to live a country where people are constantly murdering other people.

We can’t just have a country where people, being people, get mad and rowdy every once in a while and shout at or beat each other up. No, we have to live a country where people are constantly murdering other people.

We can’t have a country where a few hunters in the countryside own rifles to hunt deer. No, we must allow every manchild, as a matter of constitutional right, to shlep or shoulder an Uzi onto or into every public space and square.

We can’t have leaders and spokespersons who quietly and consistently denounce all violence. No, we have to mount elaborate martyrologies that turn every grifter into a saint, every thug into a prince, every huckster into an intellectual.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Is Mathematics Invented or Discovered?

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

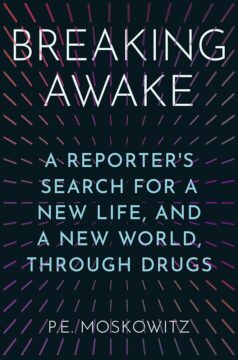

What Are Drugs For?

Emmeline Clein at The Nation:

A woman gnaws at her nails: one hand in her mouth, the other clutching the shaft of a mop, which serves as one bar of a prison cell composed of cleaning products. It’s an apt metaphor. In mid-century America, housewives were expected to polish their own gilded cages without considering how their feelings of entrapment might be related to their imprisonment in suburban homes. But by the late 1960s, even advertisers recognized that women might find such lives a little upsetting after reading The Feminine Mystique.

A woman gnaws at her nails: one hand in her mouth, the other clutching the shaft of a mop, which serves as one bar of a prison cell composed of cleaning products. It’s an apt metaphor. In mid-century America, housewives were expected to polish their own gilded cages without considering how their feelings of entrapment might be related to their imprisonment in suburban homes. But by the late 1960s, even advertisers recognized that women might find such lives a little upsetting after reading The Feminine Mystique.

The aforementioned woman is a model in a 1967 ad for a tranquilizer called Miltown. The ad acknowledged that the drug “cannot change her environment…but it can help relieve the anxiety” caused by her conditions. Ten years prior, Miltown had swept the market, selling over a billion units in the decade after Wallace Laboratories debuted it. In ads for Miltown, pharmaceutical copy suggested an incompatibility between liberatory social movements and surviving the suburbs might be to blame for a woman’s anxious distress. Nonetheless, they had a solution: A pill would go down more smoothly than a revolution.

P.E. Moskowitz deftly deconstructs this ad in a scathing examination of today’s psychopharmaceutical industrial complex in their third and newest book, Breaking Awake: A Reporter’s Search for a New Life, and a New World, Through Drugs.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Sally Mann Way

Alexandra Jacobs at the New York Times:

“We are all Sally Mann now,” one might think, gazing at the social-media streams that expose so many children. And yet none of us are Sally Mann.

“We are all Sally Mann now,” one might think, gazing at the social-media streams that expose so many children. And yet none of us are Sally Mann.

She is the art photographer both renowned and scolded for her “Family Pictures” series, which started in the mid-1980s, showing (sometimes naked) offspring of feral intensity and lasting for a decade as they grew. Her 2015 memoir, “Hold Still,” was more spellbinding than most by full-time writers.

“Art Work,” which promises guidance on the creative life, is pretty much a caboose to that bigger book. The guidance part is a little Julia Cameron, if Julia Cameron still enjoyed a nightly gin and tonic, with a dash of women’s magazine. “How I got it done” is an opening line, echoing a popular feature in The Cut. Truisms are scattered here like weeds. “It is about how you live your life, because the life you lead is your art and the art you make is your life,” is one. There’s a chapter on killing your darlings, and many sentences that boil down to the old joke: “How do you get to Carnegie Hall? Practice, practice, practice.” The rest, thankfully, is a garden of Mann: profane, literary, adventuresome.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Front Page: What do we make of our fear of porn?

Lillian Fishman in The Point:

I’m sure it’s my interest in knowing what’s normal as much as my interest in porn that led me, a few months ago, to pick up a copy of Porn, by Polly Barton. Subtitled “an oral history” and put out by the highbrow independent press Fitzcarraldo Editions, Porn is billed on the back cover as a “thrilling, thought-provoking, revelatory, revealing, joyfully informative and informal exploration of a subject that has always retained an element of the taboo.” It’s organized as a series of “chats” between the author and nineteen acquaintances, varied across age and gender and anonymized so that each subject is referred to with a number from one to nineteen. Barton is a translator who found herself surprised by the realization that she wanted to write about the ever-present but largely unspoken subject of porn, so much so that the idea kept her up at night. This preoccupation felt “deeply embarrassing” to her: “If only I was a porn connoisseur,” she writes regretfully. Her “predominant feeling towards porn,” she continues in the introduction,

I’m sure it’s my interest in knowing what’s normal as much as my interest in porn that led me, a few months ago, to pick up a copy of Porn, by Polly Barton. Subtitled “an oral history” and put out by the highbrow independent press Fitzcarraldo Editions, Porn is billed on the back cover as a “thrilling, thought-provoking, revelatory, revealing, joyfully informative and informal exploration of a subject that has always retained an element of the taboo.” It’s organized as a series of “chats” between the author and nineteen acquaintances, varied across age and gender and anonymized so that each subject is referred to with a number from one to nineteen. Barton is a translator who found herself surprised by the realization that she wanted to write about the ever-present but largely unspoken subject of porn, so much so that the idea kept her up at night. This preoccupation felt “deeply embarrassing” to her: “If only I was a porn connoisseur,” she writes regretfully. Her “predominant feeling towards porn,” she continues in the introduction,

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday Poem

Writing

often it is the only

thing

between you and

impossibility.

no drink,

no woman’s love,

no wealth

can

match it.

nothing can save

you

except

writing.

it keeps the walls

from

failing,

the hordes from

closing in.

it blasts the

darkness.

writing is the

ultimate

psychiatrist,

the kindliest

god of all the

gods.

writing stalks

death.

it knows no

quit.

and writing

laughs

at itself,

at pain.

it is the last

expectation,

the last

explanation.

that’s

what it

Is.

by Charles Bukowski

From Poetic Outlaws

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

One Community’s Experiment With a Phone-Free Childhood

Charlotte Alter in Time Magazine:

Molly Moscatiello, age 7, started riding her bike to first grade last year. There’s a crosswalk with no crossing guard, “and I had to look both ways like five times,” she says, two grown-up teeth peeking through the gap in the front of her smile. Sometimes her parents’ friends would drive past and ask if Molly needed a ride, but she’d always wave them off. “I felt a little nervous at first,” she says. “But then after a while I felt comfortable by myself.” Soon, other kids began asking to ride their bikes to school. By the end of first grade, Molly was leading a small cohort of five or six, riding to school together in Little Silver, N.J.

Molly Moscatiello, age 7, started riding her bike to first grade last year. There’s a crosswalk with no crossing guard, “and I had to look both ways like five times,” she says, two grown-up teeth peeking through the gap in the front of her smile. Sometimes her parents’ friends would drive past and ask if Molly needed a ride, but she’d always wave them off. “I felt a little nervous at first,” she says. “But then after a while I felt comfortable by myself.” Soon, other kids began asking to ride their bikes to school. By the end of first grade, Molly was leading a small cohort of five or six, riding to school together in Little Silver, N.J.

Twenty years ago, this would be as unremarkable as kids eating ice cream or playing soccer. But these days, when only about one in 10 American children walk or bike to school, Molly and her friends are more than just a gaggle of kids on bikes. They’re part of a growing countermovement against the technification of American childhood. Molly’s mother, Holly Moscatiello, is the founder of The Balance Project, a parent-run nonprofit working to rebuild communities to encourage childhood independence and get kids off screens. “We want to make it just as easy to experience life in our community as it is to go on your phone,” Moscatiello says.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday, September 11, 2025

The Craziest Band You’ve Never Heard Of

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sabrina Carpenter’s Comedy of Errors

Amanda Petrusich at The New Yorker:

The cover of “Man’s Best Friend” features a photo of Carpenter wearing heels and a black cocktail dress, on her hands and knees, before a faceless man who clutches a fistful of her hair. The image consciously hints at porn (the set includes beige wall-to-wall carpeting and heavy white drapes, as if Carpenter were crawling through a Motel 6) and sexual submission, particularly when paired with the album’s title. Reactions were swift and high-pitched. People tend to find the union of sex and violence—or sex and willing subjugation—either fun and titillating or gruesome and catastrophically sinful.

The cover of “Man’s Best Friend” features a photo of Carpenter wearing heels and a black cocktail dress, on her hands and knees, before a faceless man who clutches a fistful of her hair. The image consciously hints at porn (the set includes beige wall-to-wall carpeting and heavy white drapes, as if Carpenter were crawling through a Motel 6) and sexual submission, particularly when paired with the album’s title. Reactions were swift and high-pitched. People tend to find the union of sex and violence—or sex and willing subjugation—either fun and titillating or gruesome and catastrophically sinful.

Predictably, the hubbub surrounding the photo was eventually framed as a war between uptight virgins and godless heathens, with a quieter contingent astounded only by the fact that this kind of marketing could still be so effective. (I would also argue that there are enough heartbreak songs on the album to suggest the opposite subtext: that the title is a biting play on the various ways women are dehumanized, politically or otherwise.) Eventually, Carpenter released another cover, in which she is standing on two legs and leaning against a guy in a suit. “Here is a new alternate cover approved by God,” she wrote, on Instagram. (I laughed.)

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

David Hume vs Literature

Katie Ebner-Landy at Aeon Magazine:

It is hard to find a philosopher who writes well. One can list the good stylists on one hand: Bernard Williams, for the clear frankness of his prose; Stanley Cavell, whose writing self-reflectively folds in on itself like origami; Friedrich Nietzsche, whose dazzle and exclamation seduce many people into questionable ideas. David Hume is typically seen as part of this crowd. The 18th-century Scottish philosopher wrote in many genres: not only essays, dissertations and treatises, but dialogues, impersonated monologues and biographies. Hume adored the literary celebrities of his day, like the essayist Joseph Addison, who founded The Spectator magazine, and the French moralist Jean de La Bruyère. He was also unfailingly committed to finding a way to bridge the divide between scholars and society, between a world that was ‘learned’ and one that was ‘conversible’. However, it was Hume who helped to divide what we now call ‘literature’ from what we now call ‘philosophy’. He did so by posing a devastating challenge to the prestige of one literary tool that had long been considered a legitimate method in which to practise philosophy: the character sketch.

It is hard to find a philosopher who writes well. One can list the good stylists on one hand: Bernard Williams, for the clear frankness of his prose; Stanley Cavell, whose writing self-reflectively folds in on itself like origami; Friedrich Nietzsche, whose dazzle and exclamation seduce many people into questionable ideas. David Hume is typically seen as part of this crowd. The 18th-century Scottish philosopher wrote in many genres: not only essays, dissertations and treatises, but dialogues, impersonated monologues and biographies. Hume adored the literary celebrities of his day, like the essayist Joseph Addison, who founded The Spectator magazine, and the French moralist Jean de La Bruyère. He was also unfailingly committed to finding a way to bridge the divide between scholars and society, between a world that was ‘learned’ and one that was ‘conversible’. However, it was Hume who helped to divide what we now call ‘literature’ from what we now call ‘philosophy’. He did so by posing a devastating challenge to the prestige of one literary tool that had long been considered a legitimate method in which to practise philosophy: the character sketch.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Review of “A Short History of Stupidity” by Stuart Jeffries

Sam Leith in The Guardian:

In this clever book, Stuart Jeffries starts out at a double disadvantage, though. First: he has an excellently snappy title but it’s open to question whether stupidity can be said to have a history in any meaningful sense. The quality of stupidity is just, sort of, there; and there’s lots of it. Could you write a history of happiness, or bad luck, or knees? You’d be on firmer ground, as he recognises, historicising the concept of stupidity: a short history, in other words, of “stupidity” – how successive societies and thinkers have defined and responded to reason’s derr-brained secret sharer. As an intellectual historian who has written smart and chewy popular books about the Frankfurt School (Grand Hotel Abyss) and postmodernism (Everything, All the Time, Everywhere), he certainly has the chops for it.

In this clever book, Stuart Jeffries starts out at a double disadvantage, though. First: he has an excellently snappy title but it’s open to question whether stupidity can be said to have a history in any meaningful sense. The quality of stupidity is just, sort of, there; and there’s lots of it. Could you write a history of happiness, or bad luck, or knees? You’d be on firmer ground, as he recognises, historicising the concept of stupidity: a short history, in other words, of “stupidity” – how successive societies and thinkers have defined and responded to reason’s derr-brained secret sharer. As an intellectual historian who has written smart and chewy popular books about the Frankfurt School (Grand Hotel Abyss) and postmodernism (Everything, All the Time, Everywhere), he certainly has the chops for it.

But then there’s the second problem: definitions. Is stupidity the same thing as ignorance? As foolishness? As the unwillingness to learn (AKA obtuseness, or what the Greeks called amathia)? As the inability to draw the right conclusions from what you have learned? Is it a quality of person or a quality of action? On and off, in ordinary usage, it’s all of these. It’s a know-it-when-you-see-it (except in yourself) thing.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

China’s electric vehicle influence expands nearly everywhere – except the US and Canada

Jack Barkenbus in The Conversation:

In 2025, 1 in 4 new automotive vehicle sales globally are expected to be an electric vehicle – either fully electric or a plug-in hybrid.

In 2025, 1 in 4 new automotive vehicle sales globally are expected to be an electric vehicle – either fully electric or a plug-in hybrid.

That is a significant rise from just five years ago, when EV sales amounted to fewer than 1 in 20 new car sales, according to the International Energy Agency, an intergovernmental organization examining energy use around the world.

In the U.S., however, EV sales have lagged, only reaching 1 in 10 in 2024. By contrast, in China, the world’s largest car market, more than half of all new vehicle sales are electric.

The International Energy Agency has reported that two-thirds of fully electric cars in China are now cheaper to buy than their gasoline equivalents. With operating and maintenance costs already cheaper than gasoline models, EVs are attractive purchases.

Most EVs purchased in China are made there as well, by a range of different companies. NIO, Xpeng, Xiaomi, Zeekr, Geely, Chery, Great Wall Motor, Leapmotor and especially BYD are household names in China. As someone who has followed and published on the topic of EVs for over 15 years, I expect they will soon become as widely known in the rest of the world.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.