Samuel Hayim Brody in the Boston Review:

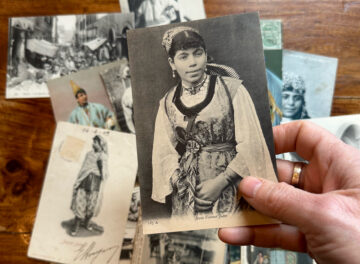

Mizrahi, a Hebrew word meaning “Eastern,” is used in the State of Israel to refer to Jews from Muslim-majority countries. Confusingly, it has widely come to replace the older term Sephardi, even though the latter traditionally means “Spanish” and has been used since medieval times to describe the Jews of the Iberian Peninsula, many of whom fled to the lands of the Ottoman Empire after their expulsion in 1492. It has never made much sense to describe the Jews of Iraq, for example—millennia-old communities with no connection to Spain or Portugal—as Sephardi. Nor does it make sense to describe Morocco as “east” of Germany. Instead, Mizrahi is an artifact of Israeli history, yoking together Jews with divergent histories in Tunisia, Yemen, and Iraq as they underwent similar experiences of immigration. But precisely because those experiences were so humiliating, the term has its opponents. In The Arab Jews: A Postcolonial Reading of Nationalism, Religion, and Ethnicity (2006), Yehouda Shenhav translates Mizrahi as “Oriental,” succinctly capturing the affects and attitudes that he and other opponents hear in it.

Mizrahi, a Hebrew word meaning “Eastern,” is used in the State of Israel to refer to Jews from Muslim-majority countries. Confusingly, it has widely come to replace the older term Sephardi, even though the latter traditionally means “Spanish” and has been used since medieval times to describe the Jews of the Iberian Peninsula, many of whom fled to the lands of the Ottoman Empire after their expulsion in 1492. It has never made much sense to describe the Jews of Iraq, for example—millennia-old communities with no connection to Spain or Portugal—as Sephardi. Nor does it make sense to describe Morocco as “east” of Germany. Instead, Mizrahi is an artifact of Israeli history, yoking together Jews with divergent histories in Tunisia, Yemen, and Iraq as they underwent similar experiences of immigration. But precisely because those experiences were so humiliating, the term has its opponents. In The Arab Jews: A Postcolonial Reading of Nationalism, Religion, and Ethnicity (2006), Yehouda Shenhav translates Mizrahi as “Oriental,” succinctly capturing the affects and attitudes that he and other opponents hear in it.

As an alternative, “Arab Jews” has a subversive quality.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Cancer is one of the most common causes of death in people, and case numbers are rising. At current rates, about one in two Australians can expect a cancer diagnosis by the age of 85. Vets, livestock farmers, pet owners and anyone who spends time around animals will also know that cancer can strike a whole range of creatures. But did you know it’s not just a disease in the animal kingdom?

Cancer is one of the most common causes of death in people, and case numbers are rising. At current rates, about one in two Australians can expect a cancer diagnosis by the age of 85. Vets, livestock farmers, pet owners and anyone who spends time around animals will also know that cancer can strike a whole range of creatures. But did you know it’s not just a disease in the animal kingdom? The first door was in Tokyo, in the Roppongi district. He said he discovered it in a state of boredom, or more exactly, in that mental state that walking in Tokyo is particularly inclined to produce—a state of visual overstimulation that is like boredom, but also strangely close to a kind of hypersensitivity, a readiness to see a hidden order suddenly emerge in the dense life of the city. The door that captured his attention had been placed across a blind alleyway. It had no special features, but was remarkable for being unmarked, without a name, bell, or knocker. Oddly, the cracked cinderblocks that framed the door on either side seemed older than the buildings that they abutted. Behind the door were the branches of some trees, giving the entire scene the hint of a hortus conclusus, a walled garden in a neighborhood that was not known for being green. An electrical conduit snaked along the pavement and over the wall.

The first door was in Tokyo, in the Roppongi district. He said he discovered it in a state of boredom, or more exactly, in that mental state that walking in Tokyo is particularly inclined to produce—a state of visual overstimulation that is like boredom, but also strangely close to a kind of hypersensitivity, a readiness to see a hidden order suddenly emerge in the dense life of the city. The door that captured his attention had been placed across a blind alleyway. It had no special features, but was remarkable for being unmarked, without a name, bell, or knocker. Oddly, the cracked cinderblocks that framed the door on either side seemed older than the buildings that they abutted. Behind the door were the branches of some trees, giving the entire scene the hint of a hortus conclusus, a walled garden in a neighborhood that was not known for being green. An electrical conduit snaked along the pavement and over the wall. The genealogy of blasphemy laws in

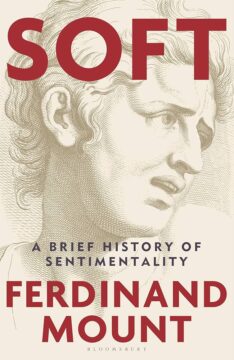

The genealogy of blasphemy laws in  Mount’s argument in this erudite, immensely entertaining book is that to be warm and witless (if by ‘witless’ one means devoid of irony, flippancy and cool) is not only to be on the side of the nice and good. It is also a form of power. Not that Mount isn’t witty – I have seldom read a work of cultural history that made me laugh out loud as frequently as this one did. But he is earnest in his belief that sentiment (called ‘sentimentality’ by those who disapprove of it) can prompt substantial social change, reverse injustices, ameliorate the lives of ill-treated people and – sentimentality alert! – enable love.

Mount’s argument in this erudite, immensely entertaining book is that to be warm and witless (if by ‘witless’ one means devoid of irony, flippancy and cool) is not only to be on the side of the nice and good. It is also a form of power. Not that Mount isn’t witty – I have seldom read a work of cultural history that made me laugh out loud as frequently as this one did. But he is earnest in his belief that sentiment (called ‘sentimentality’ by those who disapprove of it) can prompt substantial social change, reverse injustices, ameliorate the lives of ill-treated people and – sentimentality alert! – enable love.

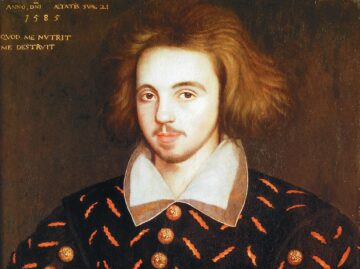

He was a radical,

He was a radical, Guillermo del Toro has been shaping his vision for Victor Frankenstein’s monster since he was 11 years old, when Mary Shelley’s classic 1818 Gothic novel became his Bible, as he put it in a conversation in August.

Guillermo del Toro has been shaping his vision for Victor Frankenstein’s monster since he was 11 years old, when Mary Shelley’s classic 1818 Gothic novel became his Bible, as he put it in a conversation in August. Many of the molecules in our bodies are

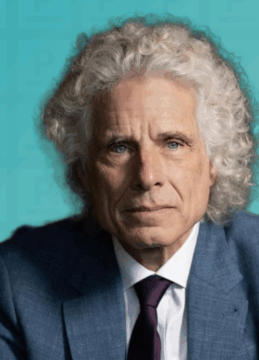

Many of the molecules in our bodies are  Steven Pinker: I’m using it in a technical sense, which is not the same as the everyday sense of conventional wisdom or something that people know. Common knowledge in the technical sense refers to a case where everyone knows that everyone knows something and everyone knows that and everyone knows it, ad infinitum. So I know something, you know it, I know that you know it, you know that I know it, I know that you know that I know it, et cetera.

Steven Pinker: I’m using it in a technical sense, which is not the same as the everyday sense of conventional wisdom or something that people know. Common knowledge in the technical sense refers to a case where everyone knows that everyone knows something and everyone knows that and everyone knows it, ad infinitum. So I know something, you know it, I know that you know it, you know that I know it, I know that you know that I know it, et cetera. Almost

Almost

At its core, The Ba***ds of Bollywood is a razor-sharp look at the dazzling yet treacherous world of

At its core, The Ba***ds of Bollywood is a razor-sharp look at the dazzling yet treacherous world of