Chris Simmas in Nature:

The Ig Nobels were founded in 1991 by Marc Abrahams, editor of satirical magazine Annals of Improbable Research. Previous winners have included the discovery that orgasm can be an effective nasal decongestant3, the levitation of live frogs using magnets4 and research on necrophilia in ducks5. In the prize’s early days, receiving one was deemed silly or even insulting by some people. Abrahams says that Robert May, the chief scientific adviser to the UK Government from 1995 to 2000, once wrote him an angry letter demanding that they stopped giving Ig Nobel prizes to British scientists.

The Ig Nobels were founded in 1991 by Marc Abrahams, editor of satirical magazine Annals of Improbable Research. Previous winners have included the discovery that orgasm can be an effective nasal decongestant3, the levitation of live frogs using magnets4 and research on necrophilia in ducks5. In the prize’s early days, receiving one was deemed silly or even insulting by some people. Abrahams says that Robert May, the chief scientific adviser to the UK Government from 1995 to 2000, once wrote him an angry letter demanding that they stopped giving Ig Nobel prizes to British scientists.

But many have come to see the Ig Nobels as career-changing in their own right.

“When we first got the phone call about winning an Ig Nobel, we honestly thought it was a prank. Once we realized it was real, we were thrilled and genuinely honored,” says Fritz Renner, a psychologist at the University of Freiburg in Germany and a winner of this year’s peace prize for work showing that drinking alcohol can improve your ability to speak in a foreign language6.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

As its September meeting approaches, the US Federal Reserve is once again coming under political pressure to lower rates. President Donald Trump has been calling for such a move for months – sometimes demanding cuts as large as

As its September meeting approaches, the US Federal Reserve is once again coming under political pressure to lower rates. President Donald Trump has been calling for such a move for months – sometimes demanding cuts as large as  My life’s mission has been to create safe, beneficial AI that will make the world a better place. But recently, I’ve been increasingly concerned about people starting to believe so strongly in AIs as conscious entities that they will advocate for “AI rights” and even citizenship. This development would represent a dangerous turn for the technology. It must be avoided. We must build AI for people, not to be people.

My life’s mission has been to create safe, beneficial AI that will make the world a better place. But recently, I’ve been increasingly concerned about people starting to believe so strongly in AIs as conscious entities that they will advocate for “AI rights” and even citizenship. This development would represent a dangerous turn for the technology. It must be avoided. We must build AI for people, not to be people. An omnipresent feature of liberal chronicles of the occupation is a fixation on how much was wasted: the $2.13 trillion spent and the 176,000 people who died. Surveying the destruction wreaked on Afghanistan, these accounts conclude, unsurprisingly, that the war was a total failure. The Taliban are once again in control of Kabul. Al Qaeda runs gold mines in Badakhshan and Takhar provinces. The Afghan army is a distant memory. This humiliation is often presented as a mystery. How could so much money—more than was spent on the Marshall Plan—and “goodwill,” in the New Yorker’s words, have achieved so little?

An omnipresent feature of liberal chronicles of the occupation is a fixation on how much was wasted: the $2.13 trillion spent and the 176,000 people who died. Surveying the destruction wreaked on Afghanistan, these accounts conclude, unsurprisingly, that the war was a total failure. The Taliban are once again in control of Kabul. Al Qaeda runs gold mines in Badakhshan and Takhar provinces. The Afghan army is a distant memory. This humiliation is often presented as a mystery. How could so much money—more than was spent on the Marshall Plan—and “goodwill,” in the New Yorker’s words, have achieved so little? I

I  One of the most striking features of insect societies is that they contain “neuter castes” of organisms that do not reproduce (worker bees, for example). That created a problem for Darwin, who conceptualized his theory of natural selection in terms of one individual outreproducing other members of its species. He solved the problem by saying that it is individual “families” (in this case, individual colonies), not just individual organisms, that reproduce differentially. Darwin treated groups composed of organisms—families, tribes, colonies—as units that get selected. In the case of the neuter castes, he reasoned, it is an advantage to such communities to have sterile members who spend their time and energy working for the prosperity of the colony as a whole rather than bearing offspring.

One of the most striking features of insect societies is that they contain “neuter castes” of organisms that do not reproduce (worker bees, for example). That created a problem for Darwin, who conceptualized his theory of natural selection in terms of one individual outreproducing other members of its species. He solved the problem by saying that it is individual “families” (in this case, individual colonies), not just individual organisms, that reproduce differentially. Darwin treated groups composed of organisms—families, tribes, colonies—as units that get selected. In the case of the neuter castes, he reasoned, it is an advantage to such communities to have sterile members who spend their time and energy working for the prosperity of the colony as a whole rather than bearing offspring. Although Sylvia Plath is best known for the cutting lyricism of Ariel (1965) and for her autobiographical novel, The Bell Jar (1963), her career goal as a writer was threefold: to write poetry, novels, and short stories. As detailed in her journals, she devoted equal time to poetry and fiction, shifting her focus to stories when she felt stalled as a poet, then returning to poetry when she lost confidence in herself as a fiction writer. More than a record of her experiences, the journals document her clear-eyed assessments of her strengths and weaknesses as a writer, her resolve to improve through relentless practice, and, especially for the short fiction, her ongoing study of markets she sought to crack: literary venues such as The New Yorker, The Atlantic Monthly, and The London Magazine; women’s magazines such as Mademoiselle, Woman’s Day, Ladies’ Home Journal; and even pulp monthlies such as True Story. As these last examples suggest, Plath’s objective as a short story writer, beginning in high school when she submitted work to Seventeen Magazine, was to make money, initially to supplement her college scholarships, and then to earn a living as a professional writer—and sustain her career as a poet—without having to teach. To expand her range of genres and contribute to the income stream, Plath also wrote nonfiction.

Although Sylvia Plath is best known for the cutting lyricism of Ariel (1965) and for her autobiographical novel, The Bell Jar (1963), her career goal as a writer was threefold: to write poetry, novels, and short stories. As detailed in her journals, she devoted equal time to poetry and fiction, shifting her focus to stories when she felt stalled as a poet, then returning to poetry when she lost confidence in herself as a fiction writer. More than a record of her experiences, the journals document her clear-eyed assessments of her strengths and weaknesses as a writer, her resolve to improve through relentless practice, and, especially for the short fiction, her ongoing study of markets she sought to crack: literary venues such as The New Yorker, The Atlantic Monthly, and The London Magazine; women’s magazines such as Mademoiselle, Woman’s Day, Ladies’ Home Journal; and even pulp monthlies such as True Story. As these last examples suggest, Plath’s objective as a short story writer, beginning in high school when she submitted work to Seventeen Magazine, was to make money, initially to supplement her college scholarships, and then to earn a living as a professional writer—and sustain her career as a poet—without having to teach. To expand her range of genres and contribute to the income stream, Plath also wrote nonfiction. Edward FitzGerald long remembered the heavenly spectacle of his younger contemporary Alfred Tennyson at Cambridge. ‘At that time he looked something like the Hyperion shorn of his Beams in Keats’s Poem’, FitzGerald wrote fifty years later, ‘with a Pipe in his mouth.’ In fact, it was not Keats that he was invoking, but Milton’s description of the recently fallen Satan – ‘Archangel ruined’, yet retaining some of his angelic glory, ‘as when the sun new-risen/Looks through the horizontal misty air/Shorn of his beams’. It is a telling connection for FitzGerald’s subconscious to have made. Charles Lamb had adduced the same passage when he described the middle-aged Coleridge, a man broken by self-obstruction and opium but still possessing some vestige of the young genius whom Lamb had so loved and revered. Coleridge’s gifts were immense but imperfectly exploited. FitzGerald seems to have seen in Tennyson a similar case.

Edward FitzGerald long remembered the heavenly spectacle of his younger contemporary Alfred Tennyson at Cambridge. ‘At that time he looked something like the Hyperion shorn of his Beams in Keats’s Poem’, FitzGerald wrote fifty years later, ‘with a Pipe in his mouth.’ In fact, it was not Keats that he was invoking, but Milton’s description of the recently fallen Satan – ‘Archangel ruined’, yet retaining some of his angelic glory, ‘as when the sun new-risen/Looks through the horizontal misty air/Shorn of his beams’. It is a telling connection for FitzGerald’s subconscious to have made. Charles Lamb had adduced the same passage when he described the middle-aged Coleridge, a man broken by self-obstruction and opium but still possessing some vestige of the young genius whom Lamb had so loved and revered. Coleridge’s gifts were immense but imperfectly exploited. FitzGerald seems to have seen in Tennyson a similar case. After our entire book club, with unprecedented unanimity, pronounced

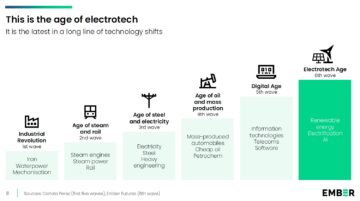

After our entire book club, with unprecedented unanimity, pronounced  Most of the discussion on the move from fossil fuels to low-carbon energy is about tackling climate change. Quite rightly: that was the main reason I got into “this” in the first place and remains a key motivation. But that framing is very much about simply solving a problem. In reality, there is also a much more exciting change going on, one that can create opportunity and radically shift how we think about energy overall.

Most of the discussion on the move from fossil fuels to low-carbon energy is about tackling climate change. Quite rightly: that was the main reason I got into “this” in the first place and remains a key motivation. But that framing is very much about simply solving a problem. In reality, there is also a much more exciting change going on, one that can create opportunity and radically shift how we think about energy overall. O

O T

T Game developer Bennett

Game developer Bennett