Excerpted from Anna Qunidlen’s book Loud and Clear:

If not for the photographs I might have a hard time believing they ever existed. The pensive infant with the swipe of dark bangs and the black button eyes of a Raggedy Andy doll. The placid baby with the yellow ringlets and the high piping voice. The sturdy toddler with the lower lip that curled into an apostrophe above her chin.

If not for the photographs I might have a hard time believing they ever existed. The pensive infant with the swipe of dark bangs and the black button eyes of a Raggedy Andy doll. The placid baby with the yellow ringlets and the high piping voice. The sturdy toddler with the lower lip that curled into an apostrophe above her chin.

All my babies are gone now. I say this not in sorrow but in disbelief. I take great satisfaction in what I have today: three almost adults, two taller than me, one closing in fast. Three people who read the same books I do and have learned not to be afraid of disagreeing with me in their opinion of them, who sometimes tell vulgar jokes that make me laugh until I choke and cry, who need razor blades and shower gel and privacy, who want to keep their doors closed more than I like. Who, miraculously, go to the bathroom, zip up their jackets, and move food from plate to mouth all by themselves. Like the trick soap I bought for the bathroom with a rubber ducky at its center, the baby is buried deep within each, barely discernible except through the unreliable haze of the past.

More here.

Ana Palacio in Project Syndicate:

Ana Palacio in Project Syndicate: anjay Subramanyam in Sidecar:

anjay Subramanyam in Sidecar: B

B By this point in “King: A Life,” Eig has established his voice. It’s a clean, clear, journalistic voice, one that employs facts the way Saul Bellow said they should be employed, each a wire that sends a current. He does not dispense two-dollar words; he keeps digressions tidy and to a minimum; he jettisons weight, on occasion, for speed. He appears to be so in control of his material that it is difficult to second-guess him.

By this point in “King: A Life,” Eig has established his voice. It’s a clean, clear, journalistic voice, one that employs facts the way Saul Bellow said they should be employed, each a wire that sends a current. He does not dispense two-dollar words; he keeps digressions tidy and to a minimum; he jettisons weight, on occasion, for speed. He appears to be so in control of his material that it is difficult to second-guess him. D

D On a bright summer day in July 2021, James Fisher rested nervously, with a newly shaved head, in a hospital bed surrounded by blinding white lights and surgeons shuffling about in blue scrubs. He was being prepped for an experimental brain surgery at West Virginia University’s Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute, a hulking research facility that overlooks the rolling peaks and cliffs of coal country around Morgantown. The hours-long procedure required impeccable precision, “down to the millimeter,” Fisher’s neurosurgeon, Ali Rezai, told me.

On a bright summer day in July 2021, James Fisher rested nervously, with a newly shaved head, in a hospital bed surrounded by blinding white lights and surgeons shuffling about in blue scrubs. He was being prepped for an experimental brain surgery at West Virginia University’s Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute, a hulking research facility that overlooks the rolling peaks and cliffs of coal country around Morgantown. The hours-long procedure required impeccable precision, “down to the millimeter,” Fisher’s neurosurgeon, Ali Rezai, told me. The writers serve up a heavy dose of fear-mongering: “Advanced AI could represent a profound change in the history of life on Earth,” their second sentence declares, “and should be planned for and managed with commensurate care and resources.”

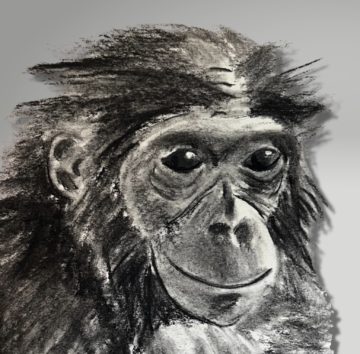

The writers serve up a heavy dose of fear-mongering: “Advanced AI could represent a profound change in the history of life on Earth,” their second sentence declares, “and should be planned for and managed with commensurate care and resources.” I had been volunteering at the ape house for four months before I was invited to meet Nathan. It was December and I’d just spent my first Christmas with the apes. Everyone but the director and I had left for the day. The night sky spilled over the glass-ceilinged, central atrium we called the greenhouse. Despite the snow outside, the greenhouse air was warm and ample. Moving toward the padlocked cage door, I felt light, as if I was about to float up into that dotted black expanse above me, rather than enter a room I’d cleaned feces and orange peels out of hours earlier.

I had been volunteering at the ape house for four months before I was invited to meet Nathan. It was December and I’d just spent my first Christmas with the apes. Everyone but the director and I had left for the day. The night sky spilled over the glass-ceilinged, central atrium we called the greenhouse. Despite the snow outside, the greenhouse air was warm and ample. Moving toward the padlocked cage door, I felt light, as if I was about to float up into that dotted black expanse above me, rather than enter a room I’d cleaned feces and orange peels out of hours earlier. The common definition of free will often has problems when relating to desire and power to choose. An alternative definition that ties free will to different outcomes for life despite one’s past is supported by the probabilistic nature of quantum physics. This definition is compatible with the Many Worlds Interpretation of quantum physics, which refutes the conclusion that randomness does not imply free will.

The common definition of free will often has problems when relating to desire and power to choose. An alternative definition that ties free will to different outcomes for life despite one’s past is supported by the probabilistic nature of quantum physics. This definition is compatible with the Many Worlds Interpretation of quantum physics, which refutes the conclusion that randomness does not imply free will.

There was hysteria in the air at 81st Street Theatre in New York. Deep within the building, behind its white neoclassical arches and away from the steady chatter of crowds of adoring fans outside, a new kind of celebrity singer was walking onto a black-and-silver stage. It was February 1929, and just a few months earlier, Rudy Vallée had been an obscure graduate best known to the listeners of WABC radio in New York. He wasn’t considered particularly good looking: one biting critic later called him

There was hysteria in the air at 81st Street Theatre in New York. Deep within the building, behind its white neoclassical arches and away from the steady chatter of crowds of adoring fans outside, a new kind of celebrity singer was walking onto a black-and-silver stage. It was February 1929, and just a few months earlier, Rudy Vallée had been an obscure graduate best known to the listeners of WABC radio in New York. He wasn’t considered particularly good looking: one biting critic later called him  Given all the attention to President Biden’s cognitive fitness for a second presidential term, it seems fair, even mandatory, to assess Donald Trump’s performance at a televised town hall in Manchester, N.H., on Wednesday night through the same lens: How clear was his thinking? How sturdy his tether to reality? How appropriate his demeanor?

Given all the attention to President Biden’s cognitive fitness for a second presidential term, it seems fair, even mandatory, to assess Donald Trump’s performance at a televised town hall in Manchester, N.H., on Wednesday night through the same lens: How clear was his thinking? How sturdy his tether to reality? How appropriate his demeanor?