Yuk Hui speaks with Daniel Birnbaum at Artforum:

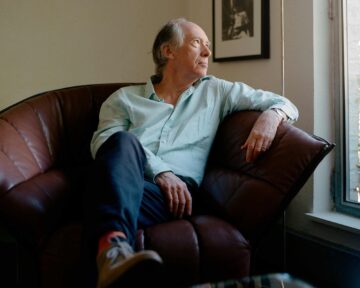

DANIEL BIRNBAUM: Many people I know are reading your recent book Post-Europe [2024] right now. It challenges us to participate in the creation of a new, globally conscious mode of thinking—an approach that is responsive to the complexities of our interconnected world. You draw upon a rich tapestry of philosophical influences, including thinkers like Gilbert Simondon, Bernard Stiegler, and Jan Patočka as well as Kitarō Nishida, to support a vision of a post-European philosophical landscape.

DANIEL BIRNBAUM: Many people I know are reading your recent book Post-Europe [2024] right now. It challenges us to participate in the creation of a new, globally conscious mode of thinking—an approach that is responsive to the complexities of our interconnected world. You draw upon a rich tapestry of philosophical influences, including thinkers like Gilbert Simondon, Bernard Stiegler, and Jan Patočka as well as Kitarō Nishida, to support a vision of a post-European philosophical landscape.

YUK HUI: It is not my main aim to fight Eurocentrism, not only because many people have been doing this for a long time, but also I think now we have to ask: What happens afterward? Does it mean a Sinocentrism, a Russocentrism, or American imperialism? What has concerned me from the outset, as you can see in all my books, is what it means to do philosophy today. Post-Europe starts with a meditation on the relation between Europe and philosophy as interpreted by various philosophers in the twentieth century, from Edmund Husserl to Jan Patočka, Jacques Derrida, and others. I was particularly drawn to the idea of the Heimat [Homeland]—Europe as the Heimat for philosophy.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

This question forms the basis of what came to be known as the ‘measurement problem’. One influential answer emerged from the mind of one of the greatest mathematicians of all time, János (or ‘John’) von Neumann, who was responsible for many important advances, not only in pure mathematics and physics but also in computer design and game theory. He pointed out that when our spin detector interacts with the electron, the state of that combined system of the detector + electron will also be described by quantum theory as a superposition of possible states. And so will the state of the even larger combined system of the observer’s eye and brain + the detector + electron. However far we extend this chain, anything physical that interacts with the system will be described by the theory as a superposition of all the possible states that combined system could occupy, and so the crucial question above will remain unanswered. Hence, von Neumann concluded, it had to be something non-physical that somehow generates the transition from a superposition to the definite state as recorded on the device and noted by the observer – namely, the observer’s consciousness. (It is this argument that is the source of much of the so-called New Age commentary on quantum mechanics about how reality must somehow be observer-dependent, and

This question forms the basis of what came to be known as the ‘measurement problem’. One influential answer emerged from the mind of one of the greatest mathematicians of all time, János (or ‘John’) von Neumann, who was responsible for many important advances, not only in pure mathematics and physics but also in computer design and game theory. He pointed out that when our spin detector interacts with the electron, the state of that combined system of the detector + electron will also be described by quantum theory as a superposition of possible states. And so will the state of the even larger combined system of the observer’s eye and brain + the detector + electron. However far we extend this chain, anything physical that interacts with the system will be described by the theory as a superposition of all the possible states that combined system could occupy, and so the crucial question above will remain unanswered. Hence, von Neumann concluded, it had to be something non-physical that somehow generates the transition from a superposition to the definite state as recorded on the device and noted by the observer – namely, the observer’s consciousness. (It is this argument that is the source of much of the so-called New Age commentary on quantum mechanics about how reality must somehow be observer-dependent, and  S

S Gary Patti leaned in to study the rows of plastic tanks, where dozens of translucent zebrafish flickered through chemically treated water. Each tank contained a different substance — some notorious, others less well understood — all known or suspected carcinogens. Patti’s team is watching them closely, tracking which fish develop tumors, to try to find clues to one of the most unsettling medical puzzles of our time: Why are so many young people getting cancer?

Gary Patti leaned in to study the rows of plastic tanks, where dozens of translucent zebrafish flickered through chemically treated water. Each tank contained a different substance — some notorious, others less well understood — all known or suspected carcinogens. Patti’s team is watching them closely, tracking which fish develop tumors, to try to find clues to one of the most unsettling medical puzzles of our time: Why are so many young people getting cancer? T

T In 1994, a strange, pixelated machine came to life on a computer screen. It read a string of instructions, copied them, and built a clone of itself — just as the Hungarian-American Polymath John von Neumann had predicted half a century earlier. It was a striking demonstration of a profound idea: that life, at its core, might be computational.

In 1994, a strange, pixelated machine came to life on a computer screen. It read a string of instructions, copied them, and built a clone of itself — just as the Hungarian-American Polymath John von Neumann had predicted half a century earlier. It was a striking demonstration of a profound idea: that life, at its core, might be computational.

States and medical societies that long worked in concert with the CDC are breaking with federal recommendations, saying they no longer have faith in them amid the turmoil and Kennedy’s criticism of vaccines. Roughly seven months after Kennedy’s nomination was confirmed, they’re rushing to draft or release their own vaccine recommendations, while new groups are forming to issue immunization guidance and advice.

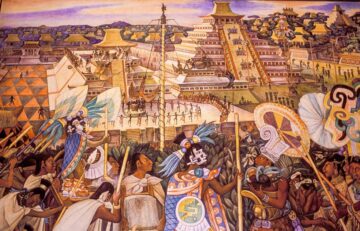

States and medical societies that long worked in concert with the CDC are breaking with federal recommendations, saying they no longer have faith in them amid the turmoil and Kennedy’s criticism of vaccines. Roughly seven months after Kennedy’s nomination was confirmed, they’re rushing to draft or release their own vaccine recommendations, while new groups are forming to issue immunization guidance and advice. When Spanish conquistador

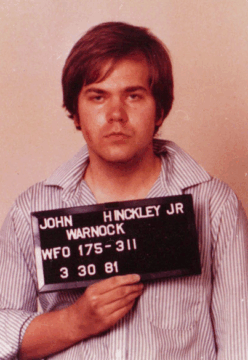

When Spanish conquistador  On the 30th of March, 1981, John Hinckley brought us into the world we all live in today. He did it by firing a .22 “Devastator” round into the chest of the president of the United States.

On the 30th of March, 1981, John Hinckley brought us into the world we all live in today. He did it by firing a .22 “Devastator” round into the chest of the president of the United States. By September 10th, Nepal had descended into a state of lawlessness, a country without a government or authority. The only national institution that survived—and that possessed the capability to restore order—was the Army, which, sheltering the civilian leadership, opened talks with representatives of the protest movement. Events then moved at dizzying speed. Within forty-eight hours, Nepal’s President had been forced to appoint an interim Prime Minister, dissolve the country’s elected Parliament, and announce new elections. As search teams set about recovering bodies from the charred government buildings, the death toll rose to more than seventy, and the number of injured exceeded two thousand.

By September 10th, Nepal had descended into a state of lawlessness, a country without a government or authority. The only national institution that survived—and that possessed the capability to restore order—was the Army, which, sheltering the civilian leadership, opened talks with representatives of the protest movement. Events then moved at dizzying speed. Within forty-eight hours, Nepal’s President had been forced to appoint an interim Prime Minister, dissolve the country’s elected Parliament, and announce new elections. As search teams set about recovering bodies from the charred government buildings, the death toll rose to more than seventy, and the number of injured exceeded two thousand.

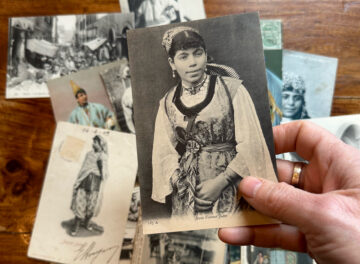

Human history is rife with contentions about the purity (and superiority) of the bloodlines of one group over another and claims over ancestral homelands.

Human history is rife with contentions about the purity (and superiority) of the bloodlines of one group over another and claims over ancestral homelands.