Category: Recommended Reading

André Watts (1946 – 2023) Pianist

Milan Kundera (1929 – 2023) Writer

Sunday Poem

Quarantine (an excerpt)

Lauds

Somehow I am sturdier, more shore

than sea-spray as I thicken through

the bedroom door. I gleam of sickness.

You give me morning, Lord, as you

give earthquake to all architecture.

I can forget.

You put that sugar

in the melon’s breath, and it is wet

with what you are. (I, too, ferment.)

You rub the hum and simple warmth

of summer from afar into the hips

of insects and of everything.

I can forget.

And like the sea,

one more machine without a memory,

I don’t believe that you made me.

Prime

I don’t believe that you made me

into this tremolo of hands,

this fever, this flat-footed dance

of tendons and the drapery

of skin along a skeleton.

I am that I am: a brittle

ribcage and the hummingbird

of breath that flickers in it.

Incrementally, I stand:

in me are eons and the cramp

of endless ancestry.

Sun is in the leaves again.

I think I see you in the wind

but then I think I see the wind.

by Malachi Black

from Poetry Society of America

Saturday, July 15, 2023

Imitation of Rigor: An Alternative History of Analytic Philosophy

Katherine Brading in Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews:

Katherine Brading in Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews:

Imitation of Rigor is a book about philosophical methods and the misuse of “rigor”, most heinously within some strands of contemporary metaphysics. The subtitle is “an alternative history of analytic philosophy” because one of Mark Wilson’s aims is to “illustrate how our subject [i.e., philosophy] might have evolved if dubious methodological suppositions hadn’t intervened along the way” (xviii). The book is rich in examples, and his argument depends on our attention to the details. I shall try to explain the big picture and hence why investing time in the details matters.

Here is one way to read the argument of the book. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, philosopher-physicist-mathematicians (Wilson’s main protagonist here is Heinrich Hertz) sought to axiomatize physics as a means of clarifying its content. Carnap and others picked up on this method, and from here was born the notion of “Theory T” (3) as an ideal of both scientific and philosophical theorizing. Contemporary metaphysicians have, in turn, taken up this method of doing philosophy, thereby placing emphasis on a particular form of rigor. This, Wilson argues, is a mistake.

The underlying assumption attributed to contemporary metaphysicians is that the output of science (in the long run) will be an axiomatized theory of everything; a single theory with unlimited scope, unified via its axiomatic structure. The gap between what is achievable in practice and such an ideal outcome is held to be a matter of no metaphysical import.

More here.

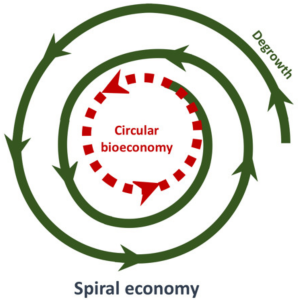

Planned Degrowth: Ecosocialism and Sustainable Human Development

John Bellamy Foster in Monthly Review:

John Bellamy Foster in Monthly Review:

The word degrowth stands for a family of political-economic approaches that, in the face of today’s accelerating planetary ecological crisis, reject unlimited, exponential economic growth as the definition of human progress. To abandon economic growth in wealthy societies means to shift to zero net capital formation. With continual technological development and the enhancement of human capabilities, mere replacement investment is able to promote steady qualitative advancements in production in mature industrial societies, while eliminating exploitative labor conditions and reducing working hours. Coupled with global redistribution of the social surplus product and reduction of waste, this would allow for vast improvements in the lives of most people. Degrowth, which specifically targets the most opulent sectors of the world population, is thus directed at the enhancement of the living conditions of the vast majority while maintaining the environmental conditions of existence and promoting sustainable human development.2

Science has established without a doubt that, in today’s “full-world economy,” it is necessary to operate within an overall Earth System budget with respect to allowable physical throughput.3 However, rather than constituting an insurmountable obstacle to human development, this can be seen as initiating a whole new stage of ecological civilization based on the creation of a society of substantive equality and ecological sustainability, or ecosocialism. Degrowth, in this sense, is not aimed at austerity, but at finding a “prosperous way down” from our current extractivist, wasteful, ecologically unsustainable, maldeveloped, exploitative, and unequal, class-hierarchical world.

More here.

Against Relics

Tony Wood in the LRB:

Tony Wood in the LRB:

The war in Ukraine has prompted a wave of self-critical reassessment among Western scholars of the former Soviet Union. Have studies of the USSR unthinkingly reproduced the logic of a Russian imperial project? Do we need to look at the Soviet period through the lens of ‘decolonisation’? The German historian Karl Schlögel’s own process of introspection began in 2014, with the annexation of Crimea and the Kremlin’s stoking of rebellion in Donbas, which he describes in the preface to The Soviet Century as the ‘drop that made my cup run over’. Russia’s leaders, he writes, had ‘exploited post-imperial phantom pains, nostalgic yearnings and fear of the loss of social status to pursue an aggressive policy’. Published in German in 2017, on the centenary of the Russian Revolution, the book is his attempt to capture the particular texture and experiences of Soviet life, memories of which are fast fading. It is also a personal reckoning, what Schlögel calls ‘a balance sheet, a sort of final account of my studies of Russia or the Soviet Union’. This doesn’t mean he plans to retire: Schlögel has another huge book out in German later this year, on American industrial modernity. But it does mark the end of his engagement with the Russia he studied and knew. It’s almost 35 years since the USSR entered its terminal crisis. As Schlögel puts it, ‘the quarter of a century that has elapsed since that time has shown how painful this process of transforming the former Soviet Union has been.’

More here.

The Franco-Prussian War And The Making of Modern Europe

Robert Gewarth at Literary Review:

In 1867, shortly after Prussia’s decisive military victories over Denmark (in 1864) and Austria (in 1866), a dinner guest asked the Prussian prime minister, Otto von Bismarck, about the prospect of a further armed conflict, this time against France. Would it be expedient to somehow provoke a French attack on Prussia in order to unify the German states against a common enemy? Bismarck rejected the idea: ‘Anyone who has ever looked into the glazed eyes of a soldier dying on the battlefield will think hard before starting a war.’

In 1867, shortly after Prussia’s decisive military victories over Denmark (in 1864) and Austria (in 1866), a dinner guest asked the Prussian prime minister, Otto von Bismarck, about the prospect of a further armed conflict, this time against France. Would it be expedient to somehow provoke a French attack on Prussia in order to unify the German states against a common enemy? Bismarck rejected the idea: ‘Anyone who has ever looked into the glazed eyes of a soldier dying on the battlefield will think hard before starting a war.’

Three years later, however, that war had become a reality, and it would radically alter the balance of power on the Continent. The Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71 was Europe’s bloodiest conflict between the Congress of Vienna (1814–15) and the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. Some two million soldiers saw action and more than 180,000 died.

more here.

Transforming Our Relationship With Sleep

David Shariatmadari and Russell Foster at The Guardian:

Professor Russell Foster CBE, head of the Sleep and Circadian Neuroscience Institute at the University of Oxford, has some relationship advice. One of the things he’s asked most often at public talks is what to do if your partner snores. First, check with your doctor if a serious condition like sleep apnoea might be to blame. Second, get some ear plugs. Third: “If you have an alternative sleeping space, then use it. It’s not a reflection of the quality of your relationship. I would say that in many cases, it’s the beginning of a better one. You’ll be more rested, you’ll be less irritated with your partner, you’ll probably have a better sense of humour, you’ll have more empathy. You’ll have more fun.”

Professor Russell Foster CBE, head of the Sleep and Circadian Neuroscience Institute at the University of Oxford, has some relationship advice. One of the things he’s asked most often at public talks is what to do if your partner snores. First, check with your doctor if a serious condition like sleep apnoea might be to blame. Second, get some ear plugs. Third: “If you have an alternative sleeping space, then use it. It’s not a reflection of the quality of your relationship. I would say that in many cases, it’s the beginning of a better one. You’ll be more rested, you’ll be less irritated with your partner, you’ll probably have a better sense of humour, you’ll have more empathy. You’ll have more fun.”

Is he speaking from personal experience? “Perhaps … ” Who’s the snorer in his marriage? “We’ll gloss over that,” he says with a chuckle.

more here.

Tarkovsky’s Solaris

Saturday Poem

Imperialism

The lady’s British accent

was fake, years later it still

infuriates. Her Cambridge estate

had china, flush toilets, English lessons,

in exchange for chores she taught me to speak

in full sentences, cured me of my accent,

a colored girl’s dream, room and board.

She taught me to say what I mean,

though to this day she refuses

to hear what I mean.

Ah, but she’d been round

the world, photographing

revolutions, toasting with Daniel

Ortega, she knew what was best

for a spic like me, nightly I

recited Chaucer by the Greek

column and the peach tree.

Miss, you tap the porcelain teapot,

time for your nicotine fit,

poof smoke away from my

face but we’re in the

same windowless room.

All I wanted was the vote,

the right to remain silent,

now you call me ungrateful,

me, writing a new constitution

full of truth and bad grammar.

Trouble, trouble, educating

coloreds. Those years I picked

your tobacco and you botched

my lungs. You taught me to spell

trigger, now I’ve got your gun.

Run Jane run run run

Lady, dear lady,

the empire

is done.

by Demetria Martinez

from El Coro

University of Massachusetts Press, 1997

What’s Happening in the Ocean, and Why It Matters to You and Me

Katharine Hayhoe in Scientific American:

Over the last five decades, we’ve burned enough coal, gas and oil, cut down enough trees, and produced enough other emissions to trap some six billion Hiroshima bombs’ worth of heat inside the climate system. Shockingly, though, only 1 percent of that heat has ended up in the atmosphere.

Over the last five decades, we’ve burned enough coal, gas and oil, cut down enough trees, and produced enough other emissions to trap some six billion Hiroshima bombs’ worth of heat inside the climate system. Shockingly, though, only 1 percent of that heat has ended up in the atmosphere.

As extreme as the “global weirding” we’re experiencing today is—people broiling under weeks of heat waves, wildfire smoke turning the skies orange, crops withering in prolonged drought, intense downpours inundating homes—most of it results from only a small fraction of all the heat that’s been building up in the climate system. Instead, the majority of that estimated 380 zettajoules of heat, nearly 90 percent of it, is going into the ocean. There, it’s setting ocean heat records year after year and driving increasingly severe marine heat waves. The ocean also absorbs about 30 percent of the carbon humans produce, adding up to almost 200 billion tons since the industrial revolution.

More here.

Barbie: A Visual Dictionary

Louis Lucero II in The New York Times:

![]() Maybe you’ve heard there’s a Barbie movie coming out?

Maybe you’ve heard there’s a Barbie movie coming out?

Well, this isn’t about that. It is, however, about the 11½ inches of intellectual property that inspired all the madness: the doll itself.

You know the one. Often blonde, always smiling, occasionally naked and neglected at the bottom of a toy chest? Chances are you do: According to Mattel, more than 100 dolls are sold every minute, and quite a few minutes have elapsed since Barbie made her debut, at a toy industry trade show, in 1959. Just as remarkable as the ways the doll has changed since then are the ways it hasn’t. Like the characters on “Sesame Street” or “South Park,” Barbie exists alongside us without quite aging with us — reflecting our times, but not our wrinkles. That adaptive consistency may play a role in maintaining her cultural ubiquity (alongside her literal ubiquity), for while the things that make Barbie Barbie may get a face lift every few years, the DNA remains unchanged.

More here.

Friday, July 14, 2023

The Ethical Puzzle of Sentient AI

Dan Falk in Undark:

As AI technology leaps forward, ethical questions sparked by human-AI interactions have taken on new urgency. “We don’t know whether to bring them into our moral circle, or exclude them,” said Birch. “We don’t know what the consequences will be. And I take that seriously as a genuine risk that we should start talking about. Not really because I think ChatGPT is in that category, but because I don’t know what’s going to happen in the next 10 or 20 years.”

In the meantime, he says, we might do well to study other non-human minds — like those of animals. Birch leads the university’s Foundations of Animal Sentience project, a European Union-funded effort that “aims to try to make some progress on the big questions of animal sentience,” as Birch put it. “How do we develop better methods for studying the conscious experiences of animals scientifically? And how can we put the emerging science of animal sentience to work, to design better policies, laws, and ways of caring for animals?”

Our interview was conducted over Zoom and by email, and has been edited for length and clarity.

More here.

Is Seneca staging a comeback? Maybe…

Cynthia Haven at The Book Haven:

For 1,500 years, no writer except Virgil held more esteem in the classical world than Seneca. And today? “We read every major tragedian in the Western tradition, except Seneca,” says poet and author Dana Gioia, a former chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts. He’s setting out to rectify that situation.

For 1,500 years, no writer except Virgil held more esteem in the classical world than Seneca. And today? “We read every major tragedian in the Western tradition, except Seneca,” says poet and author Dana Gioia, a former chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts. He’s setting out to rectify that situation.

“If Seneca’s plays survived the sack of Rome, the burning of libraries, the leaky roofs of monasteries, the appetites of beetle larvae, and the erosions of rot and mildew, they have not had a conspicuously easier time among modern critics,” he continues. “His tragedies have been dismissed both for too closely resembling Greek models and for too freely departing from them. As the classicist Frederick Ahl has noted, ‘no field of literary study rivals that of Latin poetry in so systematically belittling the quality of its works and authors.’ , “No Roman genre has suffered more consistent disparagement than tragedy.”

Seneca may be the season’s comeback kid. The former California poet laureate has just published a new verse translation of Seneca’s The Madness of Hercules (Wiseblood). Wiseblood notes that the violent and visionary play “takes the reader to the extremes of human suffering and beyond – including a descent into the Underworld, an account that echoes through the ages to Dante and Eliot.”

More here.

Orson Welles on Cold Reading

‘Idiots,’ ‘criminals’ and ‘scum’ – nasty politics highest in US since the Civil War

Thomas Zeitzoff in The Conversation:

How bad have things gotten? In my new book, I show that the level of nastiness in U.S. politics has increased dramatically. As an indication of that, I collected historical data from The New York Times on the relative frequency of stories involving Congress that contained keywords associated with nasty politics such as “smear,” “brawl” and “slander.” I found that nasty politics is more prevalent than at any time since the U.S. Civil War.

How bad have things gotten? In my new book, I show that the level of nastiness in U.S. politics has increased dramatically. As an indication of that, I collected historical data from The New York Times on the relative frequency of stories involving Congress that contained keywords associated with nasty politics such as “smear,” “brawl” and “slander.” I found that nasty politics is more prevalent than at any time since the U.S. Civil War.

Particularly following the Jan. 6. insurrection by Trump’s supporters, journalists and scholars have focused on the rise of the politics of menace. In May 2023, U.S. Capitol Police Chief Tom Manger testified before Congress and said that one of the biggest challenges the U.S. Capitol Police face today “is dealing with the sheer increase in the number of threats against the members of Congress. It’s gone up over 400% over the last six years.”

More here.

Truth, Objectivity, & Rorty – Simon Blackburn

Friday Poem

The Night I Walked Into Town

The night I walk into town

to meet my brother

I’m tripped up

by a car whose wheels rip

through a newspaper

along the white line

of the road.

The black bold

type is bleeding

I scream

but the bleeding doesn’t stop.

At the corner a man who hasn’t seen

water, food, gloved fingers

this cold, snow-blowing January

asks how many faces do I see

holding his chin up.

Twenty-five, I say

twenty-five thousand.

Naomi Ayala

from El Coro

University of Massachusetts Press, 1997

Reassessing David Foster Wallace

Patricia Lockwood at the LRB:

I have always appreciated Wallace most in his monologues and I can, like my father, hear confessions all day; Hideous Men ought to be my book. Instead, I found myself generally standing opposite to Smith’s assessments: I think ‘Forever Overhead’ is juvenelia, I find ‘Church Not Made with Hands’ to be rank fraud, and I would like to put ‘Octet’ in my ass and turn it into a diamond. Attempts to operate in the register of the profound fail; poetry deserts him, having once been insulted; and I did not laugh once, and then for a different reason, until I got to the line, ‘That’s right, the psychopath is also a mulatto.’

I have always appreciated Wallace most in his monologues and I can, like my father, hear confessions all day; Hideous Men ought to be my book. Instead, I found myself generally standing opposite to Smith’s assessments: I think ‘Forever Overhead’ is juvenelia, I find ‘Church Not Made with Hands’ to be rank fraud, and I would like to put ‘Octet’ in my ass and turn it into a diamond. Attempts to operate in the register of the profound fail; poetry deserts him, having once been insulted; and I did not laugh once, and then for a different reason, until I got to the line, ‘That’s right, the psychopath is also a mulatto.’

The truth about Brief Interviews is this: it only gets good when we’re about to be raped. We are, for the purposes of this encounter, a daffy granola hippie whose hot body is momentarily shed of her poncho, as Hideous Man #20 tells the interviewer the story of the night she unwisely got into a stranger’s car: ‘I did not fall in love with her until she had related the story of the unbelievably horrifying incident in which she was brutally accosted and held captive and very nearly killed ... By this time she was focus itself, she had merged with connection itself.’

more here.