Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

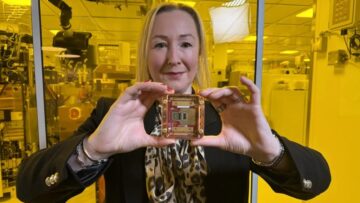

Will quantum be bigger than AI?

Zoe Kleinman in BBC:

There’s an old adage among tech journalists like me – you can either explain quantum accurately, or in a way that people understand, but you can’t do both. That’s because quantum mechanics – a strange and partly theoretical branch of physics – is a fiendishly difficult concept to get your head around. It involves tiny particles behaving in weird ways. And this odd activity has opened up the potential of a whole new world of scientific super power. Its mind-boggling complexity is probably a factor in why quantum has ended up with a lower profile than tech’s current rockstar – artificial intelligence (AI). This is despite a steady stream of recent big quantum announcements from tech giants like Microsoft and Google among others.

There’s an old adage among tech journalists like me – you can either explain quantum accurately, or in a way that people understand, but you can’t do both. That’s because quantum mechanics – a strange and partly theoretical branch of physics – is a fiendishly difficult concept to get your head around. It involves tiny particles behaving in weird ways. And this odd activity has opened up the potential of a whole new world of scientific super power. Its mind-boggling complexity is probably a factor in why quantum has ended up with a lower profile than tech’s current rockstar – artificial intelligence (AI). This is despite a steady stream of recent big quantum announcements from tech giants like Microsoft and Google among others.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

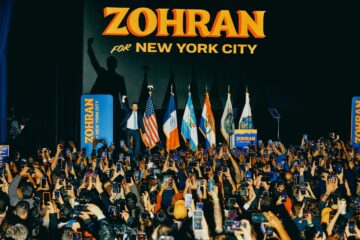

The Mamdani Era Begins

Eric Lach in The New Yorker 100:

t’s ancient history now, but when Zohran Mamdani first entertained the notion of running for mayor, he imagined himself running against Eric Adams. It was 2021, and Adams had just won a squeaker of a primary, convincing New Yorkers that what they needed in the post-COVID moment was a swaggering ex-cop who believed in good old-fashioned law and order. This summer, while I was reporting a Profile of Mamdani, Kenny Burgos, an old classmate of his from high school and a colleague in the New York State Assembly, recalled Mamdani being despondent at Adams’s victory. “He was, like, ‘Who are we going to get to run against this guy in four years?’ ” Burgos told me. “I said, ‘Why don’t you do it?’ He said, ‘I’m too young, they won’t take me seriously.’ ”

t’s ancient history now, but when Zohran Mamdani first entertained the notion of running for mayor, he imagined himself running against Eric Adams. It was 2021, and Adams had just won a squeaker of a primary, convincing New Yorkers that what they needed in the post-COVID moment was a swaggering ex-cop who believed in good old-fashioned law and order. This summer, while I was reporting a Profile of Mamdani, Kenny Burgos, an old classmate of his from high school and a colleague in the New York State Assembly, recalled Mamdani being despondent at Adams’s victory. “He was, like, ‘Who are we going to get to run against this guy in four years?’ ” Burgos told me. “I said, ‘Why don’t you do it?’ He said, ‘I’m too young, they won’t take me seriously.’ ”

Four years later, every apprehension that Mamdani and other leftists and liberals had toward an Adams mayoralty has proved justified. The Adams administration unravelled in a spray of cartoonish corruption charges that brought to mind the old grafts of Tammany Hall; the Mayor saved himself from prosecution by cutting a deal with a newly reëlected President Donald Trump. Now, as masked federal agents snatch weeping fathers and mothers from immigration court, just a few blocks from City Hall, Adams, having dropped his campaign for reëlection, is enjoying his lame-duck period. He just went on a sightseeing trip to Albania.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

‘Scamming became the new farming’: inside India’s cybercrime villages

Snigdha Poonam in The Guardian:

On the surface, the town of Jamtara appeared no different from neighbouring districts. But, if you knew where to look, there were startling differences. In the middle of spartan villages were houses of imposing size and unusual opulence. Millions of Indians knew why this was. They knew, to their cost, where Jamtara was. To them, it was no longer a place; it was a verb. You lived in fear of being “Jamtara-ed”.

On the surface, the town of Jamtara appeared no different from neighbouring districts. But, if you knew where to look, there were startling differences. In the middle of spartan villages were houses of imposing size and unusual opulence. Millions of Indians knew why this was. They knew, to their cost, where Jamtara was. To them, it was no longer a place; it was a verb. You lived in fear of being “Jamtara-ed”.

Over the past 15 years, parts of this sleepy district in the eastern state of Jharkhand had grown fabulously wealthy. This extraordinary feat of rural development was powered by young men who, armed with little more than mobile phones, had mastered the art of siphoning money from strangers’ bank accounts. The sums they pilfered were so staggering that, at times, their schemes resembled bank heists more than mere acts of financial fraud.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday Poem

Field Mouse Dangling from a Red-Tailed Hawk

My first thought wasn’t the drama above

but the bone-tired scientist I read about

who held a mirror up to a mouse,

just to watch his whiskers

………………………………………. twitch.

Proof of self-awareness, the article said.

But how to read this one,

his tail clenched in the raptor’s claw,

swaying side-to-side

like the pocketwatch of a hypnotist.

He must be watching the horizon roll up

on one side and then the other.

…….. Must be dazzled by the soft green

comforter spread below—

canopy of hickories and poplars

he’s only seen from root level

until now.

Surely the reek of the Red-tailed’s body

assails his nose (instinct and observation

sniffing out doom).

At least he’s been spared the worst part—

………. the wanting to know why.

No groping for answers for him,

no wondering if life has some meaning

death cannot destroy.

I envy how he takes it all in,

soothed by the breeze ruffling his fur.

A lesson for the rest of us perhaps,

also carried along by unseen powers,

…….. blood rushing to our faces

as we try to make sense of the view,

wishing we could match the pirouette

he’s performing,

arms and legs akimbo, standing on his head.

by Ken Hines

from Rattle #89, Fall 2025

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday, November 5, 2025

The Anthony Bourdain Reader – undiscovered gems from the charismatic chef turned writer

Sukhdev Sandhu in The Guardian:

Think Anthony Bourdain and a whole rush of TV memories flood back. There he is – in shows such as Parts Unknown and No Reservations – a gonzo gourmand trekking to backstreet nooks and favela hideouts in parts of the world where celebrity chefs fear to tread. In Beirut and Congo; savouring calamari and checking out graffiti in Tripoli; slurping rice noodles and necking bottles of cold beer with Barack Obama in Hanoi, Vietnam. One course follows another, evenings drift past midnight and he’s still chewing the fat with locals, hungry for stories – about drugs, dissidence, gristly local politics.

Think Anthony Bourdain and a whole rush of TV memories flood back. There he is – in shows such as Parts Unknown and No Reservations – a gonzo gourmand trekking to backstreet nooks and favela hideouts in parts of the world where celebrity chefs fear to tread. In Beirut and Congo; savouring calamari and checking out graffiti in Tripoli; slurping rice noodles and necking bottles of cold beer with Barack Obama in Hanoi, Vietnam. One course follows another, evenings drift past midnight and he’s still chewing the fat with locals, hungry for stories – about drugs, dissidence, gristly local politics.

But Bourdain, who killed himself aged just 61 in 2018, had always seen himself as a writer. His mother was an editor at the New York Times, and his youthful crushes were mostly beatniks and outlaws – Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs, Lester Bangs, Hunter S Thompson. (Orwell too – especially his account of a dishwasher’s life in Down and Out in Paris and London.) A college dropout, he later signed up for a writing workshop with famed editor Gordon Lish. His earliest bylines appeared in arty, downtown publications; two crime novels (Bone in the Throat, Gone Bamboo) got decent reviews but sold poorly.

Things turned around after the publication in 2000 of his bestselling memoir Kitchen Confidential. It portrayed New York’s restaurants as sweatshops, military trenches, last chance saloons for a whole bevy of social misfits. For Bourdain they were refuges.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Strategic Calculus of AI R&D Automation

Eric Drexler at AI Prospects:

Most AI research pursues incremental advances — efficiency gains, domain extensions, specific capabilities. Groups seeking transformation typically bet on conceptual breakthroughs or brute scaling. Few tackle the implementation-heavy path: integrating many components into powerful system-level capabilities.1

But implementation barriers are flattening. As I explored in “The Reality of Recursive Improvement,” AI increasingly automates its own advancement. When complex integration — heterogeneous agency architectures, malleable latent-space knowledge stores, orchestrated AI services — shifts from years of human effort to months or weeks of heavily automated exploration, the strategic landscape shifts. The question becomes not what we can build, but what we should build first: systems that can yield broad benefits — scientific tools, medical advances, structured transparency, discovery of win-win options — not those that (further) compromise biosecurity, societal epistemics, or strategic stability.

Leading AI researchers expect transformative R&D automation soon. They’re working to make it happen, and the recursive dynamics suggest they’ll succeed. The implications for research planning are profound.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

China and the US: Francis Fukuyama interviews Dan Wang

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

What Mamdani Learned from His Mother’s Films

Amardeep Singh at the Pittsburgh Review of Books:

Zohran Mamdani, as most readers know by now, is the son of a filmmaker, Mira Nair. His parents met while she was working on Mississippi Masala (1992); his father, Mahmood Mamdani, is a professor of international affairs and anthropology who had lived through the events from the 1970s described in the film.

Zohran Mamdani, as most readers know by now, is the son of a filmmaker, Mira Nair. His parents met while she was working on Mississippi Masala (1992); his father, Mahmood Mamdani, is a professor of international affairs and anthropology who had lived through the events from the 1970s described in the film.

Zohran was born 34 years ago (October 1991), and his mother’s film was released only a few months afterwards (in the U.S., February 1992). Obviously, one shouldn’t read the politics of one person through the lens of their parents, as some pro-Israel groups have been attempting to do. And in a New York Times interview with both parents from June, Mahmood Mamdani made it a point to differentiate his own ideas and beliefs from his son’s: “He’s his own person,” he said. Strikingly, Mira Nair immediately jumped in to express a contrary point of view: “I don’t agree… Of course the world we live in, and what we write and film and think about, is the world that Zohran has very much absorbed.” I’m curious about what might happen if we take that seriously: What can we learn about Zohran’s approach to politics through his mother’s approach to filmmaking?

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tutivillus Is Watching You

Amelia Soth at JSTOR Daily:

Of all the sins that might damn your soul for eternity, mumbling is probably pretty far down the list. Still, in medieval Europe, there was a demon for that: Tutivillus, who totted up all the mistakes clergymen made when singing hymns or reciting psalms. Every slurred syllable would be weighed against their souls in the final reckoning.

Of all the sins that might damn your soul for eternity, mumbling is probably pretty far down the list. Still, in medieval Europe, there was a demon for that: Tutivillus, who totted up all the mistakes clergymen made when singing hymns or reciting psalms. Every slurred syllable would be weighed against their souls in the final reckoning.

In one thirteenth-century version of the story, a holy man sees the demon in church, dragging a huge sack. According to a translation by historian Margaret Jennings, “These are the syllables and syncopated words and verses of the psalms which these very clerics in their morning prayers stole from God,” Tutivillus explains. “You can be sure I am keeping these diligently for their accusation.” You can see the scale of the stakes here: a tongue slip was no minor accident; it was theft from God.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Jubilation and historic wins: US election night 2025 – in pictures

Francis Bacon – A Tainted Talent

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How Mayor Mamdani Can Write New York’s Next Chapter

Editorial Board in The New York Times:

Mr. Mamdani, who campaigned on sweeping promises, can build a more positive legacy by focusing on tangible accomplishments. He should take notes from successful mayors, moderate and progressive alike, including Muriel Bowser of Washington, Mike Duggan of Detroit and Michelle Wu of Boston, who have delivered concrete solutions to specific problems. Mr. Mamdani cannot solve economic inequality, the problem that fueled his campaign. But he can make progress. He can build more housing. He can expand the availability of child care and good schools. He can improve bus and subway speeds.

Mr. Mamdani, who campaigned on sweeping promises, can build a more positive legacy by focusing on tangible accomplishments. He should take notes from successful mayors, moderate and progressive alike, including Muriel Bowser of Washington, Mike Duggan of Detroit and Michelle Wu of Boston, who have delivered concrete solutions to specific problems. Mr. Mamdani cannot solve economic inequality, the problem that fueled his campaign. But he can make progress. He can build more housing. He can expand the availability of child care and good schools. He can improve bus and subway speeds.

If he succeeds, he will offer a model of Democratic Party governance at a time when many Americans are skeptical of the party and have departed Democratic-run states for Republican-run ones. Across U.S. history, political progressives have a proud record of using government to ameliorate extreme inequality and enabling more Americans to live well. Mr. Mamdani has an opportunity to write the next chapter in that story. In almost every area that featured prominently in the mayoral campaign, Mr. Mamdani can improve life in New York by marrying his admirable ambition to pragmatism and compromise.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

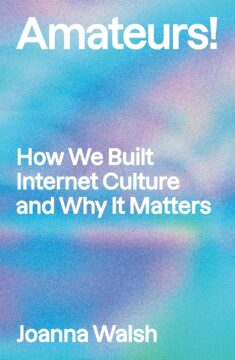

Joanna Walsh’s History Of Amateur Creativity On The Internet

Katie Kadue at Bookforum:

LONG BEFORE ELON “I am become meme” Musk sought to dismantle the federal government under the aegis of a dog meme, there were LOLcats. Founded by two software developers in 2007, icanhascheezburger.com hosted an array of image macros, foraged from forums like Something Awful or created with an in-site tool, that paired a cute cat with a caption in misspelled or ungrammatical English, as in the site’s URL. Like the countless memes that would follow and like the forgotten ones that came before, a LOLcat isn’t much on its own. Derivative and communal, it accrues meaning through use. The real memes are the shares, upvotes, and modifications we make along the way.

LONG BEFORE ELON “I am become meme” Musk sought to dismantle the federal government under the aegis of a dog meme, there were LOLcats. Founded by two software developers in 2007, icanhascheezburger.com hosted an array of image macros, foraged from forums like Something Awful or created with an in-site tool, that paired a cute cat with a caption in misspelled or ungrammatical English, as in the site’s URL. Like the countless memes that would follow and like the forgotten ones that came before, a LOLcat isn’t much on its own. Derivative and communal, it accrues meaning through use. The real memes are the shares, upvotes, and modifications we make along the way.

I Can Has Cheezburger, as the Dublin-based writer and multimedia artist Joanna Walsh reminds us, was an amateur project, an outlet for tech professionals who wanted an easier way to exchange cute cat pics after a hard day at work. In Amateurs!: How We Built Internet Culture and Why It Matters, Walsh documents how unpaid creative labor is the basis for almost everything that’s good (and much that’s bad) online, including the open-source code Linux, developed by Linus Torvalds when he was still in school (“just as a hobby, won’t be big and professional”), and even, in Walsh’s account, the World Wide Web itself.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wenesday Poem

Via Dolorosa

———————————-

Yes, these girls threading through cotton

are mourning boys whose names they’ll forget

in a few harvests. Do they know to watch out

for mice and snakes? No—they imagine

out here’s a life without danger.

They imagine they race to mystery.

———————————-

But it’s all science, really, learning how

the earth yields and heals itself. We step in

where we can with sweat, lost sleep, bruised thumbs.

But I’ll let them think it’s magic, that thorns

in their sweaters could somehow mend sorrow.

Sometimes I let myself believe the same.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday, November 4, 2025

Michael Caine and Shirley MacLaine in “Gambit”

Leann Davis Alspaugh at Acroteria:

“Go ahead, tell the end, but please don’t tell the beginning!” begs the movie poster for the 1966 film Gambit. Why would the filmmakers prefer to blow the ending rather than beginning?

“Go ahead, tell the end, but please don’t tell the beginning!” begs the movie poster for the 1966 film Gambit. Why would the filmmakers prefer to blow the ending rather than beginning?

Today’s moviegoer is accustomed to film plots that mangle chronology, forcing us to reassemble the sequence of events without clear signposts from the director. Gambit doesn’t quite go that far but it does employ a number of devices to trick the viewer into thinking a certain narrative has taken place when it has not. I can’t proceed without a spoiler alert so if that’s too much for you, please stop reading.

Gambit is a heist caper starring Michael Caine as the mastermind Harry Dean, Shirley MacLaine as the bait Nicole Chang, and Herbert Lom as Ahmad Shahbandar, the millionaire mark. Shahbandar has a priceless antique bust, Dean wants it, and Nicole is brought in to distract the millionaire. The trick is that the bust, a portrait of the ancient Chinese empress Li Su resembles Shahbandar’s beloved dead wife as well as a certain Eurasian woman—Shirley MacLaine—that Harry has discovered dancing in a shabby Hong Kong club. Harry plans to ingratiate himself with Shahbandar and use Nicole to dazzle the old man while the thief executes his plan without a hitch.

More here. [Editor’s Note: My wife and I just watched this film and enjoyed it a lot.]

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Last Breath of the Himalayas: Can We Stop the Collapse?

Kavita Bhardwaj at The Revelator:

When forests are cleared, wetlands drained, and slopes destabilized, entire ecosystems lose their balance. Floods, landslides, and erosion then hit both communities and wildlife alike.

When forests are cleared, wetlands drained, and slopes destabilized, entire ecosystems lose their balance. Floods, landslides, and erosion then hit both communities and wildlife alike.

In August a catastrophic flow of mud and debris buried parts of Dharali village in Uttarkashi. Similar disasters this year brought chaos to regions like Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, and Jammu and Kashmir. Some of these events brought worldwide headlines, if just for a few moments. Months later residents continue to struggle to recover and rebuild.

These disasters illustrate three converging factors: The mountains are fragile, the weather is getting extreme, and people are making it worse.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Derek Muller explains “The Selfish Gene” and more

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Yascha Mounk: How social media destroyed the freedoms of city life

Yascha Mounk at his own Substack:

You remember the scene: A camera at a Coldplay concert is showing audience members enjoying the show, with lead singer Chris Martin making a few friendly comments about each fan. The camera cuts to an attractive middle-aged couple in the midst of a cute embrace, with the man holding the woman from behind as they sway to the music. Then the couple spots the Jumbotron, and a perfectly choreographed series of panicked actions unfolds. The woman, shocked, covers her face, and turns away from the camera. The man dives to his left, out of the camera’s view. A younger woman, sitting behind them, and evidently in the know about what is happening, comes into view, the look on her face a poetic mix of horror and glee. “Oh, what?” Martin comments. “Either they’re having an affair or they’re just very shy.”

You remember the scene: A camera at a Coldplay concert is showing audience members enjoying the show, with lead singer Chris Martin making a few friendly comments about each fan. The camera cuts to an attractive middle-aged couple in the midst of a cute embrace, with the man holding the woman from behind as they sway to the music. Then the couple spots the Jumbotron, and a perfectly choreographed series of panicked actions unfolds. The woman, shocked, covers her face, and turns away from the camera. The man dives to his left, out of the camera’s view. A younger woman, sitting behind them, and evidently in the know about what is happening, comes into view, the look on her face a poetic mix of horror and glee. “Oh, what?” Martin comments. “Either they’re having an affair or they’re just very shy.”

It didn’t take long for the internet to confirm Martin’s first hypothesis. The man was the CEO of a tech company, someone known in his milieu but far from famous. The woman was the company’s head of HR (or, to cite the correct corporate appellation, its Chief People Officer). Both were promptly tarred-and-feathered in the public sphere, and nearly as promptly resigned from their jobs.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

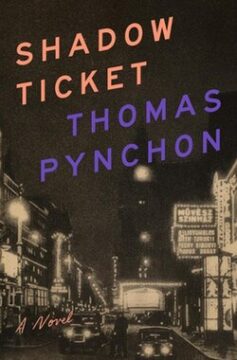

Thomas Pynchon’s Novel Of International Espionage And White-Cheddar Crime

Lisa Borst at The Baffler:

In a 1990 review of Thomas Pynchon’s Vineland, John Leonard described the book as “unbuttoned, as though the author-god had gone to a ballgame.” Vineland is maybe my personal favorite Pynchon, although choosing one feels like trying to pick the best lava lamp in a chandelier store, so volcanically exceptional is he to American letters, which can’t help but look square and patrician by comparison. I love all the unbuttoned Pynchons—the later, “easier” novels, the stuff that didn’t take decades to research or at least doesn’t make a show of it, the loosies. Vineland, Inherent Vice, Bleeding Edge, even Against the Day (a long book, but a fun and limber one): these are where Pynchon’s essential pleasures, the makeshift utopias and ludicrous jokes (some perilously low-hanging) that make him so miraculous, get the most room to roam.

In a 1990 review of Thomas Pynchon’s Vineland, John Leonard described the book as “unbuttoned, as though the author-god had gone to a ballgame.” Vineland is maybe my personal favorite Pynchon, although choosing one feels like trying to pick the best lava lamp in a chandelier store, so volcanically exceptional is he to American letters, which can’t help but look square and patrician by comparison. I love all the unbuttoned Pynchons—the later, “easier” novels, the stuff that didn’t take decades to research or at least doesn’t make a show of it, the loosies. Vineland, Inherent Vice, Bleeding Edge, even Against the Day (a long book, but a fun and limber one): these are where Pynchon’s essential pleasures, the makeshift utopias and ludicrous jokes (some perilously low-hanging) that make him so miraculous, get the most room to roam.

Shadow Ticket, Pynchon’s tenth book and the third installment in his recent trio of detective novels, pushes the limits of “unbuttoned.” It’s a novel that’s barely wearing a shirt. By which I mean it’s both stylistically stripped-down—sparse on the stuff that literature usually comes dressed in, like description and interiority—and horny, in a polite, pre-Code sort of way.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.