Judy Berman in Time Magazine:

Horror is ubiquitous on TV at this time of year, and those of us who love a good scare—myself very much included—usually look forward to it. Unfortunately, October 2025’s selection of IP expansions (IT: Welcome to Derry, Anne Rice’s Talamasca) and true crime murdersploitation left me mostly cold. You will find one worthwhile serial-killer story among this month’s highlights, though—plus a thriller with the deceptively spooky title Down Cemetery Road, a docudrama that resurrects Margaret Thatcher, an in-depth profile of a filmmaker who stares into the darkness of the human soul, and a dispatch from the delightfully unhinged brain of Tim Robinson.

Horror is ubiquitous on TV at this time of year, and those of us who love a good scare—myself very much included—usually look forward to it. Unfortunately, October 2025’s selection of IP expansions (IT: Welcome to Derry, Anne Rice’s Talamasca) and true crime murdersploitation left me mostly cold. You will find one worthwhile serial-killer story among this month’s highlights, though—plus a thriller with the deceptively spooky title Down Cemetery Road, a docudrama that resurrects Margaret Thatcher, an in-depth profile of a filmmaker who stares into the darkness of the human soul, and a dispatch from the delightfully unhinged brain of Tim Robinson.

Mr. Scorsese (Apple TV)

It’s always fascinating to see one great artist consider another. Over the course of a career spanning more than half a century, Martin Scorsese has directed essential documentaries on so many luminaries: Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones, the Beatles, the Band, Elia Kazan, Fran Lebowitz, and the list goes on. Now, Rebecca Miller—the filmmaker, novelist, daughter of Arthur Miller, and wife of two-time Scorsese leading man Daniel Day-Lewis—has turned her lens on Marty, in an excellent five-part docuseries rightly framed as a “portrait.” It’s immediately clear that Miller was the ideal director for this project, wise about both the psychological toll of uncompromising artistry and the pain artists so often inflict on the people who love them.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

IN THESE PROFOUNDLY unsettling times, literary criticism can seem a little frivolous. We’re no longer slouching toward some imagined autocratic future; we’re midway through the dissolution of the American experiment. We’ve got concentration camps and mass deportations, the senseless dismantlement of essential federal agencies, military personnel on foot patrol in our nation’s capital. There’s a relentless assault on public media, public education, public service, public health, and anything else that an earlier generation would have reasonably considered to be in the public’s interest. It’s dystopian and thoroughly demoralizing. And the most we can manage, it would seem, is to twiddle our thumbs like so many complicit functionaries, doomscrolling against the inevitable.

IN THESE PROFOUNDLY unsettling times, literary criticism can seem a little frivolous. We’re no longer slouching toward some imagined autocratic future; we’re midway through the dissolution of the American experiment. We’ve got concentration camps and mass deportations, the senseless dismantlement of essential federal agencies, military personnel on foot patrol in our nation’s capital. There’s a relentless assault on public media, public education, public service, public health, and anything else that an earlier generation would have reasonably considered to be in the public’s interest. It’s dystopian and thoroughly demoralizing. And the most we can manage, it would seem, is to twiddle our thumbs like so many complicit functionaries, doomscrolling against the inevitable. A

A We’ve moved beyond what the magazine n+1 identified as the unadorned qualities of post-2008 cityscapes. That insubstantial, flat and gray “fast-casual modernism” is complemented by a social-media-approved cookie-cutter skin that has been thrust upon our major and midsize cities in a dismal consensus. It’s no surprise that New York is getting its very own versions of two neo-yuppie Los Angeles mainstays: the meme-ified health-food store Erewhon and the Los Feliz cafe Maru (which I love, of course). America’s two largest cities have most quickly been reshaped by the internet, succumbing to an epidemic of increasingly blank streets for the moneyed classes, the bicoastal and the terminally online people who covet luxury. It’s possible now to walk down Columbus Avenue and mistake it for Abbot Kinney in Venice Beach.

We’ve moved beyond what the magazine n+1 identified as the unadorned qualities of post-2008 cityscapes. That insubstantial, flat and gray “fast-casual modernism” is complemented by a social-media-approved cookie-cutter skin that has been thrust upon our major and midsize cities in a dismal consensus. It’s no surprise that New York is getting its very own versions of two neo-yuppie Los Angeles mainstays: the meme-ified health-food store Erewhon and the Los Feliz cafe Maru (which I love, of course). America’s two largest cities have most quickly been reshaped by the internet, succumbing to an epidemic of increasingly blank streets for the moneyed classes, the bicoastal and the terminally online people who covet luxury. It’s possible now to walk down Columbus Avenue and mistake it for Abbot Kinney in Venice Beach. Cognitivism, which has permeated society—as evidenced by the omnipresence of the terms “cognitive” and “cognition”—has perpetuated a traditional view of thought and intelligence as phenomena of inextricable complexity, and therefore phenomena that we can hardly imagine recreating artificially. This approach has prevented us from anticipating and continues to prevent us from understanding what is happening. Behaviorism, on the other hand, allows us to apprehend complexity through the simple processes from which it emerges and provides the framework for understanding current AI. According to this approach, here is what is essential to understand about psychology: the environment shapes the behavior of organisms via two processes, natural selection and associative learning; the first process structures the brain over generations, establishing a “pre-wiring” that provides the basis upon which the second process structures behaviors over the course of the individual’s life.

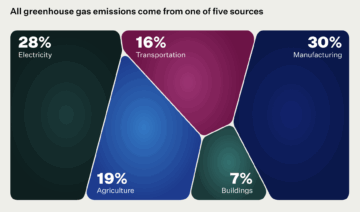

Cognitivism, which has permeated society—as evidenced by the omnipresence of the terms “cognitive” and “cognition”—has perpetuated a traditional view of thought and intelligence as phenomena of inextricable complexity, and therefore phenomena that we can hardly imagine recreating artificially. This approach has prevented us from anticipating and continues to prevent us from understanding what is happening. Behaviorism, on the other hand, allows us to apprehend complexity through the simple processes from which it emerges and provides the framework for understanding current AI. According to this approach, here is what is essential to understand about psychology: the environment shapes the behavior of organisms via two processes, natural selection and associative learning; the first process structures the brain over generations, establishing a “pre-wiring” that provides the basis upon which the second process structures behaviors over the course of the individual’s life. Although climate change will have serious consequences—particularly for people in the poorest countries—it will not lead to humanity’s demise. People will be able to live and thrive in most places on Earth for the foreseeable future. Emissions projections have gone down, and with the right policies and investments, innovation will allow us to drive emissions down much further.

Although climate change will have serious consequences—particularly for people in the poorest countries—it will not lead to humanity’s demise. People will be able to live and thrive in most places on Earth for the foreseeable future. Emissions projections have gone down, and with the right policies and investments, innovation will allow us to drive emissions down much further. In the summer of 1966, while he was an undergraduate at Indiana University, Hudson Freeze went to live in a cabin on the edge of Yellowstone National Park. He was working for microbiologist Thomas Brock, who was convinced that certain microorganisms were living at surprisingly high temperatures. Dodging bears, and the traffic jams they caused, Freeze visited the hot springs every day to sample their bacteria. On 19 September, Freeze succeeded in growing a sample of yellowish microbes from Mushroom Spring. Under a microscope, he found an array of cells collected from the near-boiling fluids. “I was seeing something that nobody had ever seen before,” says Freeze, now at the Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute in La Jolla, California. “I still get goosebumps when I remember looking into the microscope.”

In the summer of 1966, while he was an undergraduate at Indiana University, Hudson Freeze went to live in a cabin on the edge of Yellowstone National Park. He was working for microbiologist Thomas Brock, who was convinced that certain microorganisms were living at surprisingly high temperatures. Dodging bears, and the traffic jams they caused, Freeze visited the hot springs every day to sample their bacteria. On 19 September, Freeze succeeded in growing a sample of yellowish microbes from Mushroom Spring. Under a microscope, he found an array of cells collected from the near-boiling fluids. “I was seeing something that nobody had ever seen before,” says Freeze, now at the Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute in La Jolla, California. “I still get goosebumps when I remember looking into the microscope.” A writer explores the semiotic. All artists work with signs and meanings. For me, writing is a form of semiotic sabotage. It is full of bold advances and strategic retreats, and above all it is shot through with deliberate acts of obstructionism.

A writer explores the semiotic. All artists work with signs and meanings. For me, writing is a form of semiotic sabotage. It is full of bold advances and strategic retreats, and above all it is shot through with deliberate acts of obstructionism. Why are people wrong all the time, anyway? Is it because we human beings are too good at being irrational, using our biases and motivated reasoning to convince ourselves of something that isn’t quite accurate? Or is it something different — unmotivated reasoning, or “unthinkingness,” an unwillingness to do the cognitive work that most of us are actually up to if we try? Gordon Pennycook wants to argue for the latter, and this simple shift has important consequences, including for strategies for getting people to be less susceptible to misinformation and conspiracies.

Why are people wrong all the time, anyway? Is it because we human beings are too good at being irrational, using our biases and motivated reasoning to convince ourselves of something that isn’t quite accurate? Or is it something different — unmotivated reasoning, or “unthinkingness,” an unwillingness to do the cognitive work that most of us are actually up to if we try? Gordon Pennycook wants to argue for the latter, and this simple shift has important consequences, including for strategies for getting people to be less susceptible to misinformation and conspiracies. In most superhero stories, the villains are so deranged or evil that they operate outside the boundaries of society. “SuperKitties” and its ilk focus on characters who do bad things from within the boundaries of society: Their actions are hurtful or wrong, but they were committed because the character believed they were reasonable or permitted. Children may get more out of this type of character because this is exactly the kind of conflict they experience with parents, siblings and classmates; it is even a situation they may find themselves in, having done something that seemed fun or helpful only to receive a scolding, warning or lecture in response.

In most superhero stories, the villains are so deranged or evil that they operate outside the boundaries of society. “SuperKitties” and its ilk focus on characters who do bad things from within the boundaries of society: Their actions are hurtful or wrong, but they were committed because the character believed they were reasonable or permitted. Children may get more out of this type of character because this is exactly the kind of conflict they experience with parents, siblings and classmates; it is even a situation they may find themselves in, having done something that seemed fun or helpful only to receive a scolding, warning or lecture in response. When Robert Hooke gazed through his microscope at a slice of cork and coined the term ‘cell’ in 1665, he was really looking at just the walls of the dead cells. The squishy contents typically found within would become objects of ongoing study. But for many plant scientists, the walls themselves faded into the background. They were considered passive containers for the exciting biology inside.

When Robert Hooke gazed through his microscope at a slice of cork and coined the term ‘cell’ in 1665, he was really looking at just the walls of the dead cells. The squishy contents typically found within would become objects of ongoing study. But for many plant scientists, the walls themselves faded into the background. They were considered passive containers for the exciting biology inside. How do we know when others know what we know? Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker’s latest book, When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows, delves into how ‘common knowledge’ can cement or explode social relations. Common knowledge — awareness of mutual understanding — can explain the

How do we know when others know what we know? Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker’s latest book, When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows, delves into how ‘common knowledge’ can cement or explode social relations. Common knowledge — awareness of mutual understanding — can explain the  G

G