C. Brandon Ogbunu at Undark:

Questions about voting patterns have long been the object of inquiry from thinkers across a breadth of fields, and especially in social science domains like political science, psychology, and economics. Studies in these realms are often reflective and retrospective, telling detailed stories of how, for example, the American electorate has changed over decades. These scholars ideally slow-cook these stories through meticulous analysis before they enter a peer review process that itself operates at a snail’s pace.

Questions about voting patterns have long been the object of inquiry from thinkers across a breadth of fields, and especially in social science domains like political science, psychology, and economics. Studies in these realms are often reflective and retrospective, telling detailed stories of how, for example, the American electorate has changed over decades. These scholars ideally slow-cook these stories through meticulous analysis before they enter a peer review process that itself operates at a snail’s pace.

But because coverage of elections is such a time-sensitive endeavor, we often rely on the quick trigger of political journalists to tell us the stories at the timescale that we need to grasp the world around us. To have enough information to cast a vote on election day, we may need to know how the race for mayor has changed on a given day and what those changes mean. The problem here, well known throughout journalism, is that the rush to report can sensationalize or oversimplify voting dynamics.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

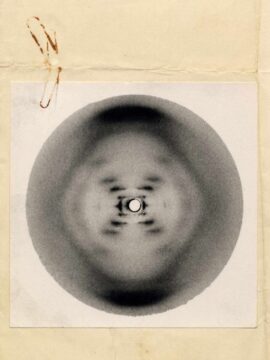

The discovery of the structure of DNA in the early 1950s is one of the most riveting dramas in the history of science, crammed with brilliant research, naked ambition, intense rivalry and outright deception. There were many players, including Rosalind Franklin, a wizard of X-ray crystallography, and Francis Crick, a physicist in search of the secret of life. Now, with

The discovery of the structure of DNA in the early 1950s is one of the most riveting dramas in the history of science, crammed with brilliant research, naked ambition, intense rivalry and outright deception. There were many players, including Rosalind Franklin, a wizard of X-ray crystallography, and Francis Crick, a physicist in search of the secret of life. Now, with  A couple of weeks before his

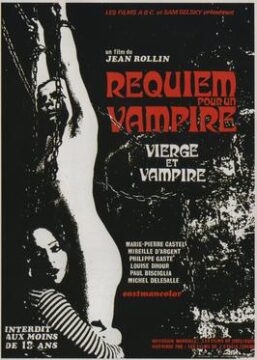

A couple of weeks before his  You know instantly when you’re in Kate Atkinson’s world. It’s dark, slightly Gothic, mordantly funny, keenly observed, highly textured and always full of surprises. Atkinson my not be easy to characterize — she’s a master of every genre she tries — but one thing’s for sure: You’ll be completely absorbed.

You know instantly when you’re in Kate Atkinson’s world. It’s dark, slightly Gothic, mordantly funny, keenly observed, highly textured and always full of surprises. Atkinson my not be easy to characterize — she’s a master of every genre she tries — but one thing’s for sure: You’ll be completely absorbed. As a child, I imagined America as a truly democratic place where I could speak, disagree, and still listen. I even used to quote half seriously, “I disagree with what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it,” from an American movie I watched, when I argued with my little friends. That line felt like a promise. I thought that was what America looked like. Later, I realized that the promise was harder to keep. I remember when I saw Charlie Kirk being killed while debating, I felt lost, totally lost. What about freedom of speech?

As a child, I imagined America as a truly democratic place where I could speak, disagree, and still listen. I even used to quote half seriously, “I disagree with what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it,” from an American movie I watched, when I argued with my little friends. That line felt like a promise. I thought that was what America looked like. Later, I realized that the promise was harder to keep. I remember when I saw Charlie Kirk being killed while debating, I felt lost, totally lost. What about freedom of speech? I attended The Curve, a conference of ~350 top AI lab leaders and scientists, safety activists and alarmists, political advisors and lobbyists, journalists, and civil society leaders. The event took place in Lighthaven, a quirky cluster of houses in Berkeley that have been retrofitted into small conference spaces. Many sessions were in living room-sized spaces, so it was all very personable and informal — an impressive feat by the organizing team.

I attended The Curve, a conference of ~350 top AI lab leaders and scientists, safety activists and alarmists, political advisors and lobbyists, journalists, and civil society leaders. The event took place in Lighthaven, a quirky cluster of houses in Berkeley that have been retrofitted into small conference spaces. Many sessions were in living room-sized spaces, so it was all very personable and informal — an impressive feat by the organizing team. “Today I would say the whole world should be paying particular attention to this class of problem, which I’ll call the problem of democracy,” she noted in her preamble.

“Today I would say the whole world should be paying particular attention to this class of problem, which I’ll call the problem of democracy,” she noted in her preamble. I’m going to roll up my sleeves and attempt a dirty, but I think necessary, job. I’m going to try to defend the humanities, or at least humanities scholarship, as it exists in its current form. I should say, before I do, that my road to something like a permanent job in the humanities has been a winding one. I remember, as a graduate student, being driven absolutely insane by how sanguine my professors were about our discipline. They were trying to reassure me, I think. But they succeeded only in making me envy and then resent them. So, to you, the reader, I say: wherever you’ve been, I’ve been there, too. I know the adjunct life. I know precarity. I know indifference. I know downright hostility. I’ve taught at diploma mills and in the Ivy League and everything in between. I understand.

I’m going to roll up my sleeves and attempt a dirty, but I think necessary, job. I’m going to try to defend the humanities, or at least humanities scholarship, as it exists in its current form. I should say, before I do, that my road to something like a permanent job in the humanities has been a winding one. I remember, as a graduate student, being driven absolutely insane by how sanguine my professors were about our discipline. They were trying to reassure me, I think. But they succeeded only in making me envy and then resent them. So, to you, the reader, I say: wherever you’ve been, I’ve been there, too. I know the adjunct life. I know precarity. I know indifference. I know downright hostility. I’ve taught at diploma mills and in the Ivy League and everything in between. I understand. As far back as 1980, the American philosopher

As far back as 1980, the American philosopher  F

F I learned to drive in the parking lot of what was then called the A&P supermarket, which marked the turnoff to a house my family owned then, by a cove and across from a small harbor. The idea was that my father would teach me. During the summers I spent a good deal of time alone with my father on a nineteen-foot sailboat called the Nausicaa. In the Odyssey, Nausicaa, the daughter of King Alcinous and Queen Arete, is washing clothes by an inlet on the island of Phaeacia, near where Odysseus, after a shipwreck, has washed ashore. When he appears, roused from slumber by the splash in a tidepool engineered by the goddess Athena, Nausicaa’s startled handmaidens flee, but “Alcinous’ daughter held fast, for Athena planted courage within her heart.”

I learned to drive in the parking lot of what was then called the A&P supermarket, which marked the turnoff to a house my family owned then, by a cove and across from a small harbor. The idea was that my father would teach me. During the summers I spent a good deal of time alone with my father on a nineteen-foot sailboat called the Nausicaa. In the Odyssey, Nausicaa, the daughter of King Alcinous and Queen Arete, is washing clothes by an inlet on the island of Phaeacia, near where Odysseus, after a shipwreck, has washed ashore. When he appears, roused from slumber by the splash in a tidepool engineered by the goddess Athena, Nausicaa’s startled handmaidens flee, but “Alcinous’ daughter held fast, for Athena planted courage within her heart.” These books were born in Western Europe and North America at the confluence of imperial expansion, mass literacy and the rise of the translation industry, popular periodicals and book serialisation. They owed their existence to the arrival of boys as a separate – and increasingly profitable – segment of the book-reading public. Robert Louis Stevenson described Treasure Island as “a story for boys”; Haggard, his imitator and competitor, offered King Solomon’s Mines “to boys and to those who are boys at heart”.

These books were born in Western Europe and North America at the confluence of imperial expansion, mass literacy and the rise of the translation industry, popular periodicals and book serialisation. They owed their existence to the arrival of boys as a separate – and increasingly profitable – segment of the book-reading public. Robert Louis Stevenson described Treasure Island as “a story for boys”; Haggard, his imitator and competitor, offered King Solomon’s Mines “to boys and to those who are boys at heart”. When millions of people suddenly couldn’t load familiar websites and apps during the

When millions of people suddenly couldn’t load familiar websites and apps during the