Hello Readers and Writers,

We received a large number of submissions of sample essays in our search for new columnists. Most of them were excellent and it was very hard deciding whom to accept and whom not to. If you did not get selected, it does not at all mean that we didn’t like what you sent; we just have a limited number of slots and also sometimes we have too many people who want to write about the same subject. Today we welcome to 3QD the following persons, in alphabetical order by last name:

- Jerry Cayford

- Richard Farr

- Barbara Fischkin

- Barry Goldman

- Joseph Milholland

- Gus Mitchell

- Muna Nassir

- Nils Peterson

- Nate Sheff

- Oliver Waters

I will be in touch with all of you in the next days to schedule a start date. The “Monday Magazine” page will be updated with short bios and photographs of the new writers on the day they start.

Thanks to all of the people who sent samples of writing to us. It was a pleasure to read them all. Congratulations to the new writers!

Best wishes,

Abbas

Ngũgĩ is a giant of African writing, and to a Kenyan writer like me he looms especially large. Alongside writers such as

Ngũgĩ is a giant of African writing, and to a Kenyan writer like me he looms especially large. Alongside writers such as  Starting during Barack Obama’s first run for president, I began making a number of predictions that struck most people as outlandish at the time. First was the prediction, based in part on Obama’s rise,

Starting during Barack Obama’s first run for president, I began making a number of predictions that struck most people as outlandish at the time. First was the prediction, based in part on Obama’s rise,  As Americans, we find ourselves in a culture that so fetishizes success that it cannot tolerate failure. So it deals with it in one of two ways. The first is to view failure in individualized and atomized terms, blaming the losers for their losses. The second, which is equally insidious, is to be so disdainful of failure that it insists that what looks like failure in fact is a mere “stepping-stone to success,” in the philosopher Costica Bradatan’s phrase. Thus the platitudinous self-help bromides that we find adorned on a framed poster in a bank teller’s cubicle (“Failure is success in progress”) or shouted by a fitness influencer hawking protein powder on TikTok (“There’s no failure that willpower can’t turn into success”). In a culture that demands overcoming against all odds, even failure has been commodified by the American self-help industrial complex: rebranded not as a devastating and possibly life-altering event but as a blip en route to a chest-thumping achievement, accomplishment, or acquisition.

As Americans, we find ourselves in a culture that so fetishizes success that it cannot tolerate failure. So it deals with it in one of two ways. The first is to view failure in individualized and atomized terms, blaming the losers for their losses. The second, which is equally insidious, is to be so disdainful of failure that it insists that what looks like failure in fact is a mere “stepping-stone to success,” in the philosopher Costica Bradatan’s phrase. Thus the platitudinous self-help bromides that we find adorned on a framed poster in a bank teller’s cubicle (“Failure is success in progress”) or shouted by a fitness influencer hawking protein powder on TikTok (“There’s no failure that willpower can’t turn into success”). In a culture that demands overcoming against all odds, even failure has been commodified by the American self-help industrial complex: rebranded not as a devastating and possibly life-altering event but as a blip en route to a chest-thumping achievement, accomplishment, or acquisition. It’s a warm summer afternoon and you have everything set-up for a lovely afternoon in the great outdoors. You’ve got a cold drink in hand and the smell of sausages sizzling away is making you hungry. You fold out the camp chair and dust of the cobwebs, ready to chill out. Just then, the all too familiar buzz of a fly echoes in your ear. And so the onslaught begins. You swat and they just come back, gluttons for the punishment of your lazily swiping hand. Sure, they’re a nuisance. But flies get a bad rap and we’re here to try and convince you that they could in fact be seen as the true heroes of the Aussie summer.

It’s a warm summer afternoon and you have everything set-up for a lovely afternoon in the great outdoors. You’ve got a cold drink in hand and the smell of sausages sizzling away is making you hungry. You fold out the camp chair and dust of the cobwebs, ready to chill out. Just then, the all too familiar buzz of a fly echoes in your ear. And so the onslaught begins. You swat and they just come back, gluttons for the punishment of your lazily swiping hand. Sure, they’re a nuisance. But flies get a bad rap and we’re here to try and convince you that they could in fact be seen as the true heroes of the Aussie summer. The Republican political consultant Richard Berman is something of a legend, often credited with taking the art of negative campaigning on behalf of undisclosed corporate clients to the next level. When “60 Minutes” did a profile of him, in 2007, he was portrayed as the “Dr. Evil” of the Washington influence game. More than a decade later, when I visited his office in downtown D.C., he still had a tongue-in-cheek “Dr. Evil” nameplate on his desk. (“If they call you Mr. Nice Guy, would that be better?”

The Republican political consultant Richard Berman is something of a legend, often credited with taking the art of negative campaigning on behalf of undisclosed corporate clients to the next level. When “60 Minutes” did a profile of him, in 2007, he was portrayed as the “Dr. Evil” of the Washington influence game. More than a decade later, when I visited his office in downtown D.C., he still had a tongue-in-cheek “Dr. Evil” nameplate on his desk. (“If they call you Mr. Nice Guy, would that be better?”  Jeffrey Herlihy-Mera in the LA Review of Books:

Jeffrey Herlihy-Mera in the LA Review of Books: Lee Harris in Foreign Policy:

Lee Harris in Foreign Policy: I

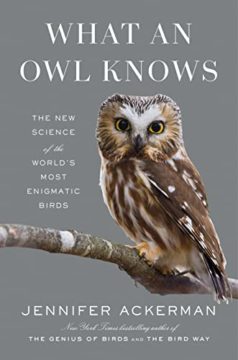

I While reading “What an Owl Knows,” by the science writer Jennifer Ackerman, I was reminded that my daughter once received a gift of a winter jacket festooned with colorful owls. At the time I thought of the coat as merely cute, but it turns out that the very existence of such merchandise reflects certain cultural assumptions about the birds: namely, that they are salutary and good.

While reading “What an Owl Knows,” by the science writer Jennifer Ackerman, I was reminded that my daughter once received a gift of a winter jacket festooned with colorful owls. At the time I thought of the coat as merely cute, but it turns out that the very existence of such merchandise reflects certain cultural assumptions about the birds: namely, that they are salutary and good. Studying “Hamlet,” the revenge play about a rotten kingdom, I tried for years to fathom Hamlet’s motives, state of mind, family web, obsessions.

Studying “Hamlet,” the revenge play about a rotten kingdom, I tried for years to fathom Hamlet’s motives, state of mind, family web, obsessions. I can tell you where it all started because I remember the moment exactly. It was late and I’d just finished the novel I’d been reading. A few more pages would send me off to sleep, so I went in search of a short story. They aren’t hard to come by around here; my office is made up of piles of books, mostly advance-reader copies that have been sent to me in hopes I’ll write a quote for the jacket. They arrive daily in padded mailers—novels, memoirs, essays, histories—things I never requested and in most cases will never get to. On this summer night in 2017, I picked up a collection called Uncommon Type, by Tom Hanks. It had been languishing in a pile by the dresser for a while, and I’d left it there because of an unarticulated belief that actors should stick to acting. Now for no particular reason I changed my mind. Why shouldn’t Tom Hanks write short stories? Why shouldn’t I read one? Off we went to bed, the book and I, and in doing so put the chain of events into motion. The story has started without my realizing it. The first door opened and I walked through.

I can tell you where it all started because I remember the moment exactly. It was late and I’d just finished the novel I’d been reading. A few more pages would send me off to sleep, so I went in search of a short story. They aren’t hard to come by around here; my office is made up of piles of books, mostly advance-reader copies that have been sent to me in hopes I’ll write a quote for the jacket. They arrive daily in padded mailers—novels, memoirs, essays, histories—things I never requested and in most cases will never get to. On this summer night in 2017, I picked up a collection called Uncommon Type, by Tom Hanks. It had been languishing in a pile by the dresser for a while, and I’d left it there because of an unarticulated belief that actors should stick to acting. Now for no particular reason I changed my mind. Why shouldn’t Tom Hanks write short stories? Why shouldn’t I read one? Off we went to bed, the book and I, and in doing so put the chain of events into motion. The story has started without my realizing it. The first door opened and I walked through.