Homesickness as Particle Theory

An atom cannot exist

if the center does not hold.

Matter cannot hold

if the atoms swing apart

too far—

that summer night:

I could feel the pieces of my life

circling away from me in distances so vast

the volume of separation

seemed infinite.

I caught

the wisp of my grandfather’s

pipe smoke,

the saturated indigo

of a green downstate summer evening,

every window open

to the chance of sleep

in deep humidity,

washed in waves of cricket song

and the far pungent howl of a coyote

edging the cornfields.

All in seconds

lifted away.

Those of us who revere Octavia Butler’s work and have never stopped mourning her passing do so in part, I suspect, because we know that no matter what happens in this Universe there will never be anyone like Butler again—not as a person and certainly not as an artist. Like Toni Morrison, Butler was a literary eucatastrophe, (a sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on to recur), a literary Kwisatz Haderach (Butler loved Dune) that occurs so very rarely in a culture and only if it is lucky.

Those of us who revere Octavia Butler’s work and have never stopped mourning her passing do so in part, I suspect, because we know that no matter what happens in this Universe there will never be anyone like Butler again—not as a person and certainly not as an artist. Like Toni Morrison, Butler was a literary eucatastrophe, (a sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on to recur), a literary Kwisatz Haderach (Butler loved Dune) that occurs so very rarely in a culture and only if it is lucky.

It’s somewhat amazing that cosmology, the study of the universe as a whole, can make any progress at all. But it has, especially so in recent decades. Partly that’s because nature has been kind to us in some ways: the universe is quite a simple place on large scales and at early times. Another reason is a leap forward in the data we have collected, and in the growing use of a powerful tool: computer simulations. I talk with cosmologist Andrew Pontzen on what we know about the universe, and how simulations have helped us figure it out. We also touch on hot topics in cosmology (early galaxies discovered by JWST) as well as philosophical issues (are simulations data or theory?).

It’s somewhat amazing that cosmology, the study of the universe as a whole, can make any progress at all. But it has, especially so in recent decades. Partly that’s because nature has been kind to us in some ways: the universe is quite a simple place on large scales and at early times. Another reason is a leap forward in the data we have collected, and in the growing use of a powerful tool: computer simulations. I talk with cosmologist Andrew Pontzen on what we know about the universe, and how simulations have helped us figure it out. We also touch on hot topics in cosmology (early galaxies discovered by JWST) as well as philosophical issues (are simulations data or theory?). Ecological collapse is likely to start sooner than previously believed, according to a new study that models how tipping points can amplify and accelerate one another.

Ecological collapse is likely to start sooner than previously believed, according to a new study that models how tipping points can amplify and accelerate one another. ‘G

‘G In “Planta Sapiens,” Paco Calvo, a philosopher of plant behavior, and his co-author, Natalie Lawrence, present the idea that flora are intelligent — that is, capable of cognition. In Calvo’s opinion, people pay more attention to animals than plants and this may explain why some of plants’ remarkable abilities have been overlooked. Our evolutionary history may also shape our reduced attention to the subject; plants are, after all, unlikely to attack people.

In “Planta Sapiens,” Paco Calvo, a philosopher of plant behavior, and his co-author, Natalie Lawrence, present the idea that flora are intelligent — that is, capable of cognition. In Calvo’s opinion, people pay more attention to animals than plants and this may explain why some of plants’ remarkable abilities have been overlooked. Our evolutionary history may also shape our reduced attention to the subject; plants are, after all, unlikely to attack people. Patrick Bigger and Federico Sibaja in Phenomenal World:

Patrick Bigger and Federico Sibaja in Phenomenal World: Tim Sahay in Foreign Policy:

Tim Sahay in Foreign Policy: Timothy Andersen in Aeon:

Timothy Andersen in Aeon: Vowell’s unforgettable early contribution to a relatively early incarnation of This American Life (back in 1999), in which she performed a similar feat, though that time unfurling the entire history of the United States drawing on the 720 degree panorama (360 degrees of space compounded by 360 degrees of time) available from just one street corner in Chicago. To wit, this one here: Michigan Avenue as it courses over the Chicago River and intersects with Wacker Drive.

Vowell’s unforgettable early contribution to a relatively early incarnation of This American Life (back in 1999), in which she performed a similar feat, though that time unfurling the entire history of the United States drawing on the 720 degree panorama (360 degrees of space compounded by 360 degrees of time) available from just one street corner in Chicago. To wit, this one here: Michigan Avenue as it courses over the Chicago River and intersects with Wacker Drive. One of the strangest, most audacious winks Fear of Kathy Acker bestows is the fact that its contents have little to do with her. Yet Skelley pays substantial tribute to Acker in his introduction, pointing to his own literary puberty in which she was a catalyst: “[H]er vastly funny, scary, sexy portals to expression opened at a susceptible period. […] It was a nascent and fertile moment when Kathy, at the peak of her powers, disrupted me, erupted in me.” After hearing the chapbook discussed on the radio in the 1980s, Acker sent Skelley a postcard that would become a crowning endorsement of the work: “[D]espite my dislike of seeing my own name I think you’re a good writer […] Never what’s expected,” she wrote.

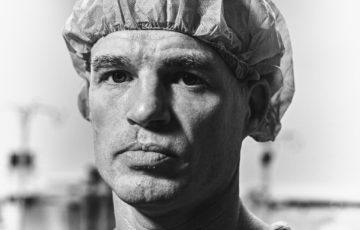

One of the strangest, most audacious winks Fear of Kathy Acker bestows is the fact that its contents have little to do with her. Yet Skelley pays substantial tribute to Acker in his introduction, pointing to his own literary puberty in which she was a catalyst: “[H]er vastly funny, scary, sexy portals to expression opened at a susceptible period. […] It was a nascent and fertile moment when Kathy, at the peak of her powers, disrupted me, erupted in me.” After hearing the chapbook discussed on the radio in the 1980s, Acker sent Skelley a postcard that would become a crowning endorsement of the work: “[D]espite my dislike of seeing my own name I think you’re a good writer […] Never what’s expected,” she wrote. Some years ago, a psychiatrist named Wendy Dean read an article about a physician who died by suicide. Such deaths were distressingly common, she discovered. The suicide rate among doctors appeared to be even higher than the rate among active military members, a notion that startled Dean, who was then working as an administrator at a U.S. Army medical research center in Maryland. Dean started asking the physicians she knew how they felt about their jobs, and many of them confided that they were struggling. Some complained that they didn’t have enough time to talk to their patients because they were too busy filling out electronic medical records. Others bemoaned having to fight with insurers about whether a person with a serious illness would be preapproved for medication. The doctors Dean surveyed were deeply committed to the medical profession. But many of them were frustrated and unhappy, she sensed, not because they were burned out from working too hard but because the health care system made it so difficult to care for their patients.

Some years ago, a psychiatrist named Wendy Dean read an article about a physician who died by suicide. Such deaths were distressingly common, she discovered. The suicide rate among doctors appeared to be even higher than the rate among active military members, a notion that startled Dean, who was then working as an administrator at a U.S. Army medical research center in Maryland. Dean started asking the physicians she knew how they felt about their jobs, and many of them confided that they were struggling. Some complained that they didn’t have enough time to talk to their patients because they were too busy filling out electronic medical records. Others bemoaned having to fight with insurers about whether a person with a serious illness would be preapproved for medication. The doctors Dean surveyed were deeply committed to the medical profession. But many of them were frustrated and unhappy, she sensed, not because they were burned out from working too hard but because the health care system made it so difficult to care for their patients. Hype springs eternal in medicine, but lately the horizon of new possibility seems almost blindingly bright. “I’ve been running my research lab for almost 30 years,” says Jennifer Doudna, a biochemist at the University of California, Berkeley. “And I can say that throughout that period of time, I’ve just never experienced what we’re seeing over just the last five years.”

Hype springs eternal in medicine, but lately the horizon of new possibility seems almost blindingly bright. “I’ve been running my research lab for almost 30 years,” says Jennifer Doudna, a biochemist at the University of California, Berkeley. “And I can say that throughout that period of time, I’ve just never experienced what we’re seeing over just the last five years.”