Chris Niebauer at IAI:

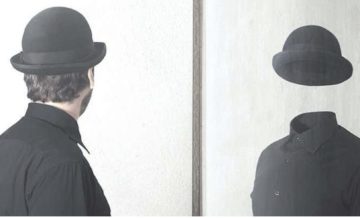

For most ordinary people, it is assumed that “we” exist somewhere within the skull, and this self is free to make decisions. This self is the “captain” of the body, controlling our behaviors and making our life choices. The problem is that neither this inner self nor free will exists the way most think that it does. Research conclusively demonstrates that these are just stories that we humans make up. Michael Gazzaniga’s groundbreaking research eventually concludes that the self is just a fiction created by the brain. Humans make up such stories, believe in them, and rarely question their validity. However, this isn’t the bad news it may appear to be. It is good news, but it will take a while to grasp.

For most ordinary people, it is assumed that “we” exist somewhere within the skull, and this self is free to make decisions. This self is the “captain” of the body, controlling our behaviors and making our life choices. The problem is that neither this inner self nor free will exists the way most think that it does. Research conclusively demonstrates that these are just stories that we humans make up. Michael Gazzaniga’s groundbreaking research eventually concludes that the self is just a fiction created by the brain. Humans make up such stories, believe in them, and rarely question their validity. However, this isn’t the bad news it may appear to be. It is good news, but it will take a while to grasp.

More here.

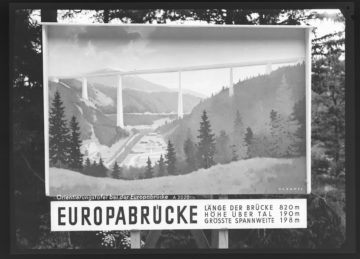

Before pondering the locations of action cinema (and thus the vectors of our own nostalgias and aspirations), let us briefly rehearse the mystique of Tom Cruise’s action-hero Method-acting, and its storied relationship to cinema as art and industry.

Before pondering the locations of action cinema (and thus the vectors of our own nostalgias and aspirations), let us briefly rehearse the mystique of Tom Cruise’s action-hero Method-acting, and its storied relationship to cinema as art and industry. Palantir’s founding team, led by investor Peter Thiel and Alex Karp, wanted to create a company capable of using new data integration and data analytics technology — some of it developed to fight online payments fraud — to solve problems of law enforcement, national security, military tactics, and warfare. They called it Palantir, after the magical stones in The Lord of the Rings. Palantir, founded in 2003, developed its tools fighting terrorism after September 11, and has done extensive work for government agencies and corporations though much of its work is secret. It went

Palantir’s founding team, led by investor Peter Thiel and Alex Karp, wanted to create a company capable of using new data integration and data analytics technology — some of it developed to fight online payments fraud — to solve problems of law enforcement, national security, military tactics, and warfare. They called it Palantir, after the magical stones in The Lord of the Rings. Palantir, founded in 2003, developed its tools fighting terrorism after September 11, and has done extensive work for government agencies and corporations though much of its work is secret. It went  There is an old temple at Chavín de Huántar. The archaeological site lies halfway between Peru’s tropical lowlands and the coast, near the confluence of the Mosna and Huanchesca Rivers, tucked between jagged mountain cordilleras. Inside the temple, a U-shaped flat-topped pyramid, intricate carvings of animals exotic to the highlands cover the stone passageways that form a labyrinth between chambers. Jaguars. Harpy eagles. Caimans. Anacondas. Devotees once came here to consult oracles and perform bloodletting rituals. In the middle of the central cruciform room, illuminated by a beam of sunlight, stands a fifteen-foot-tall, triangular granite monolith that connects the floor to the ceiling. A figure has been etched into the rock. Googly eyes sit above a broad snout with round nostrils. Curly hair ending in snake heads, like Medusa, frames a snarling face. One hand is raised in the air, palm forward, as if permitting passage to another world. The other lays down at its side. Five curving claws protrude from its feet, where worshippers once laid lavish gifts of food and ceramics. This is El Lanzón.

There is an old temple at Chavín de Huántar. The archaeological site lies halfway between Peru’s tropical lowlands and the coast, near the confluence of the Mosna and Huanchesca Rivers, tucked between jagged mountain cordilleras. Inside the temple, a U-shaped flat-topped pyramid, intricate carvings of animals exotic to the highlands cover the stone passageways that form a labyrinth between chambers. Jaguars. Harpy eagles. Caimans. Anacondas. Devotees once came here to consult oracles and perform bloodletting rituals. In the middle of the central cruciform room, illuminated by a beam of sunlight, stands a fifteen-foot-tall, triangular granite monolith that connects the floor to the ceiling. A figure has been etched into the rock. Googly eyes sit above a broad snout with round nostrils. Curly hair ending in snake heads, like Medusa, frames a snarling face. One hand is raised in the air, palm forward, as if permitting passage to another world. The other lays down at its side. Five curving claws protrude from its feet, where worshippers once laid lavish gifts of food and ceramics. This is El Lanzón.

One can’t help but feel a sense of wonder reading about the bar-tailed godwit, a bird the size of a football, whose winter migration can take it from Alaska to New Zealand in one marathon flight across the Pacific Ocean. The ornithologists who’ve helped us understand the phenomenon of migration inspire wonder as well. Their ingenuity and zeal are at the heart of Rebecca Heisman’s delightful debut, “Flight Paths: How a Passionate and Quirky Group of Pioneering Scientists Solved the Mystery of Bird Migration.”

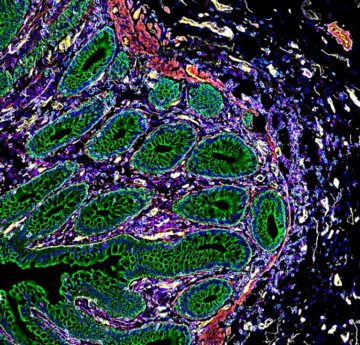

One can’t help but feel a sense of wonder reading about the bar-tailed godwit, a bird the size of a football, whose winter migration can take it from Alaska to New Zealand in one marathon flight across the Pacific Ocean. The ornithologists who’ve helped us understand the phenomenon of migration inspire wonder as well. Their ingenuity and zeal are at the heart of Rebecca Heisman’s delightful debut, “Flight Paths: How a Passionate and Quirky Group of Pioneering Scientists Solved the Mystery of Bird Migration.” Detailed maps of the cells in human organs show how the placenta commandeers the maternal blood supply, how kidney cells transition from healthy to diseased states and how cells in the intestine organize themselves into distinct neighbourhoods. These atlases, published on 19 July in Nature

Detailed maps of the cells in human organs show how the placenta commandeers the maternal blood supply, how kidney cells transition from healthy to diseased states and how cells in the intestine organize themselves into distinct neighbourhoods. These atlases, published on 19 July in Nature For the first time, the majority of information we consume as a species is controlled by algorithms built to capture our emotional attention. As a result, we hear more angry voices shouting fearful opinions and we see more threats and frightening news simply because these are the stories most likely to engage us. This engagement is profitable for everyone involved: producers, journalists, creators, politicians, and, of course, the platforms themselves.

For the first time, the majority of information we consume as a species is controlled by algorithms built to capture our emotional attention. As a result, we hear more angry voices shouting fearful opinions and we see more threats and frightening news simply because these are the stories most likely to engage us. This engagement is profitable for everyone involved: producers, journalists, creators, politicians, and, of course, the platforms themselves. The Earth’s atmosphere is good for some things, like providing something to breathe. But it does get in the way of astronomers, who have been successful at launching orbiting telescopes into space. But gravity and the ground are also useful for certain things, like walking around. The Moon, fortunately, provides gravity and a solid surface without any complications of a thick atmosphere — perfect for astronomical instruments. Building telescopes and other kinds of scientific instruments on the Moon is an expensive and risky endeavor, but the time may have finally arrived. I talk with astrophysicist Joseph Silk about the case for doing astronomy from the Moon, and what special challenges and opportunities are involved.

The Earth’s atmosphere is good for some things, like providing something to breathe. But it does get in the way of astronomers, who have been successful at launching orbiting telescopes into space. But gravity and the ground are also useful for certain things, like walking around. The Moon, fortunately, provides gravity and a solid surface without any complications of a thick atmosphere — perfect for astronomical instruments. Building telescopes and other kinds of scientific instruments on the Moon is an expensive and risky endeavor, but the time may have finally arrived. I talk with astrophysicist Joseph Silk about the case for doing astronomy from the Moon, and what special challenges and opportunities are involved. Imagine the entire cohort of U.S. graduating high school students this year as a group of one thousand bright-eyed 18-year-olds: kids of every class and race, spanning the whole spectrum of talent, wealth and oppression. What should the goal of progressive politics be for them? Where should attention be focused?

Imagine the entire cohort of U.S. graduating high school students this year as a group of one thousand bright-eyed 18-year-olds: kids of every class and race, spanning the whole spectrum of talent, wealth and oppression. What should the goal of progressive politics be for them? Where should attention be focused? O

O Things get especially interesting every weekend night about two and a half hours into the show, when Swift diverges from her otherwise precisely orchestrated set to perform two “surprise songs” from her catalog acoustically, never to be repeated at a later show, or so she says. The number of viewers in the live streams increase threefold, and fans on TikTok broadcast their feral reactions to Swift’s choices, which become ripe for close reading. “If I hear ‘friends break up’ I’m gonna kill myself,” one user watching the Cincinnati show

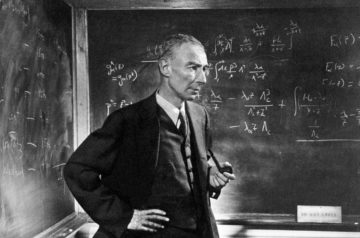

Things get especially interesting every weekend night about two and a half hours into the show, when Swift diverges from her otherwise precisely orchestrated set to perform two “surprise songs” from her catalog acoustically, never to be repeated at a later show, or so she says. The number of viewers in the live streams increase threefold, and fans on TikTok broadcast their feral reactions to Swift’s choices, which become ripe for close reading. “If I hear ‘friends break up’ I’m gonna kill myself,” one user watching the Cincinnati show  This week, the much anticipated movie Oppenheimer hits theaters, giving famed filmmaker Christopher Nolan’s take on the theoretical physicist who during World War II led the Manhattan Project to develop the first atomic bomb. J. Robert Oppenheimer, who died in 1967, is known as a charismatic leader, eloquent public intellectual, and Red Scare victim who in 1954 lost his security clearance in part because of his earlier associations with suspected Communists. To learn about Oppenheimer the scientist, Science spoke with David C. Cassidy, a physicist and historian emeritus at Hofstra University. Cassidy has authored or edited 10 books, including J. Robert Oppenheimer and the American Century.

This week, the much anticipated movie Oppenheimer hits theaters, giving famed filmmaker Christopher Nolan’s take on the theoretical physicist who during World War II led the Manhattan Project to develop the first atomic bomb. J. Robert Oppenheimer, who died in 1967, is known as a charismatic leader, eloquent public intellectual, and Red Scare victim who in 1954 lost his security clearance in part because of his earlier associations with suspected Communists. To learn about Oppenheimer the scientist, Science spoke with David C. Cassidy, a physicist and historian emeritus at Hofstra University. Cassidy has authored or edited 10 books, including J. Robert Oppenheimer and the American Century.