Category: Recommended Reading

Michael Gambon (1940 – 2023) Actor

Saturday, September 30, 2023

The Iliad by Homer, translated by Emily Wilson review – a bravura feat

Edith Hall in The Guardian:

Edith Hall in The Guardian:

Translations of Homer matter to cultural history. John Keats once looked into the “wide expanse” of George Chapman’s 1611 translation of the Iliad and breathed “its pure serene”. Alexander Pope’s rhyming version of the Iliad (1715-1720) brought a canonical ancient author to a much larger audience than ever before, its readers now including literate workers and women who had never had the opportunity to learn Greek. It had been through 27 editions by 1790. The early 20th-century Labour MP Will Crooks, who grew up in poverty and was dazzled by a twopenny second-hand copy, later recalled that “pictures of romance and beauty I had never dreamed of suddenly opened up before my eyes. I was transported from the East End to an enchanted land.”

New translations also proliferated. There were nearly 50 English-language versions in the 19th century, at least 30 in the 20th, and a dozen or more already in the 21st. Some are outstanding: Richmond Lattimore (1951) brilliantly reproduced Homer’s rolling dactylic hexameters; the trench-traumatised Robert Graves (1959) evoked Achilles’ alienation and brutality; Robert Fitzgerald (1974) grasped the Iliad’s pace and acoustic beauty and Christopher Logue (War Music, 1981) its visceral impact. Robert Fagles’s translation (1990) has relentless forward drive and readability. Do we really need another? If it is this one by Emily Wilson, then we certainly do.

More here. Additionally, here is a critical review by Valerie Stivers in Compact Magazine.

Warfare Dressed as Water Policy

Andrew Ross in Boston Review:

This summer, we are lucky if we get water in my home once in twenty days,” reported Ramzy, a nearby villager from Jifna, as he filled his grimy four-gallon tanks from a tap near the open road. We were standing at a spring just a few miles north of Ramallah, a city with an annual rainfall greater than London but which, like the rest of Palestine, suffers from a condition of artificial water scarcity at the hands of Israel. “There is a great lake of water beneath us,” Ramzy pointed out (referring to the bountiful Mountain Aquifer), “but we do not see any of its benefits. If we try to dig a well, we will be fined, and maybe worse.” Like the others lined up with their containers, he was relying on the largesse of a man who had found a spring while digging the foundations for a new house and decided to make the water available to the public. I would later learn from the regional water service provider that the spring’s water was not all that safe to drink from: it had been contaminated by the cesspits in the surrounding villages. But for Ramzy and his needy family, there were few alternatives. Water from the private tanker trucks that are ubiquitous on the West Bank’s streets and roads comes at a steep price, and its quality is often not much better.

This summer, Palestine’s ongoing water crisis reached dangerous new heights. Next to the surge in settler activity, anxiety about the lack of domestic water supply was the most common topic on people’s lips. And for many strapped households like Ramzy’s, the safety of what they could obtain to drink was often not a priority. Among the factors contributing to the particularly acute shortage were the unprecedented summer heat, Israel’s cruel reduction, by 25 percent, of supply to the governorates of Hebron and Bethlehem, resource pressure from the post–COVID-19 influx of summer residents from the Palestinian diaspora, and the seizure of artisan springs by settlers all across the West Bank.

More here.

Naomi Klein’s Journey Into the Unnerving World of Naomi Wolf

Laura Marsh in The New Republic:

Laura Marsh in The New Republic:

Torching your own reputation is usually a onetime engagement. Credibility is finite, and once it’s gone, there is not much left to burn. A reporter who got their sources mixed up once will surprise no one next time they bungle a story; a writer who spreads conspiracy theories is soon known as a crank.

Those rules have somehow not held true for the writer Naomi Wolf. A notable feature of her career has been her ability to repeat the act of self-immolation over and over, singeing others along the way. In the first year of the pandemic, Wolf reliably drew fresh surprise and dismay when she made outlandish claims about the tyranny of public health measures and the dangers of vaccines. Each time that she declared, usually via Twitter, that Anthony Fauci was Satan, or that children who wore masks had lost the ability to smile, that the vaccines were a “software platform that can receive uploads,” or that she had uncovered a plot by Apple “to deliver vaccines [with] nanopatticles [sic] that let you travel back in time,” ripples of consternation followed. Was this really the same Naomi Wolf, the author of a widely read feminist treatise, The Beauty Myth; a longtime contributor to the liberal newspaper The Guardian; a familiar face on MSNBC—a fixture in liberal media since the 1990s? What had happened to her?

These questions proved remarkably durable. The latest Naomi Wolf development was a frequent spectacle on Twitter, and the subject of a steady drip of think pieces. “A Modern Feminist Classic Changed My Life. Was it Actually Garbage?” Rebecca Onion asked of The Beauty Myth in Slate, in March 2021. A few months later, Business Insider documented “Naomi Wolf’s Slide from Feminist, Democratic Party Icon to the ‘Conspiracist Whirlpool,’” and this magazine contemplated “The Madness of Naomi Wolf” in June that year, after Twitter suspended her account.

More here.

Defanged

Eric Foner reviews Jonathan Eig’s King: The Life of Martin Luther King in the LRB:

In March 1968, only a few days before his assassination, Martin Luther King Jr visited Long Beach, a suburb of New York City, at the invitation of a local NAACP leader. Like many suburbs at that time, Long Beach was effectively a segregated community, with an African American population living in a tiny ghetto and working in the homes of local white families. I grew up in Long Beach, but by 1968 had moved to the city. My parents, however, still lived there, and my outspoken mother arranged to see the city manager, a non-partisan administrator who exercised the authority normally enjoyed by an elected mayor. ‘A great American is visiting Long Beach,’ she declared, urging the manager to hold a reception for King at City Hall. He refused: ‘He’s a troublemaker and we don’t want him here.’

This minor incident goes unmentioned in Jonathan Eig’s new biography of King, of course. But it illustrates a theme to which Eig returns several times. People of every political persuasion now claim King as a forebear. But during his lifetime, King and the civil rights movement aroused considerable opposition, not only in the South. The government sought to destroy King’s reputation. With the authorisation of John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, the FBI listened in on his phone calls with close associates and planted informers in his circle. Convinced the civil rights movement was a communist plot, J. Edgar Hoover’s G-men gathered recordings of his trysts with women and mailed them to his house, accompanied by an unsigned letter suggesting that he take his own life.

More here.

Jean-Paul Sartre: The Road to Freedom

The Double Life of Bob Dylan Volume 2: 1966-2021

Kate Mossman at The Guardian:

Who will get to write the last word on Bob Dylan? A number of men compete for the honour of world authority – Michael Gray, Howard Sounes, Greil Marcus, Robert Shelton, Clinton Heylin – and relations aren’t always good. In his introduction to volume one of this humungous book (published in 2021), Heylin said that Sounes wrote depressingly well-trundled semi-literate strolls. Sounes pointed out how overlong and baggy Heylin’s Dylan books are (he’s written 13): “All he knows is how to tell me what Visions of Johanna means in his mind.”

Who will get to write the last word on Bob Dylan? A number of men compete for the honour of world authority – Michael Gray, Howard Sounes, Greil Marcus, Robert Shelton, Clinton Heylin – and relations aren’t always good. In his introduction to volume one of this humungous book (published in 2021), Heylin said that Sounes wrote depressingly well-trundled semi-literate strolls. Sounes pointed out how overlong and baggy Heylin’s Dylan books are (he’s written 13): “All he knows is how to tell me what Visions of Johanna means in his mind.”

Rock completism, as dry, competitive and cerebral as it appears to be, is driven by a fierce, possessive love. Heylin has loved Dylan since he was 12 years old: he is now 63.

more here.

‘Germany 1923’: When Democracy Held Nazism at Bay

Jennifer Szalai at the New York Times:

The insurrection failed. The system held — at least for a time. In November 1923, when a young demagogue named Adolf Hitler tried to start a Nazi revolution from a Munich beer hall, his attempted coup was so disorganized that it swiftly degenerated into bumbling confusion. One participant later testified that the operation was such a farce that he whispered to others, “Play along with this comedy.”

The insurrection failed. The system held — at least for a time. In November 1923, when a young demagogue named Adolf Hitler tried to start a Nazi revolution from a Munich beer hall, his attempted coup was so disorganized that it swiftly degenerated into bumbling confusion. One participant later testified that the operation was such a farce that he whispered to others, “Play along with this comedy.”

Instead of seizing power, Hitler acquired a dislocated shoulder and a short stint in prison. But in “Germany 1923,” the historian Volker Ullrich reminds us that the haphazard events of the so-called Beer Hall Putsch “were eminently serious.” A decade later, Hitler would be appointed Germany’s chancellor, and the Weimar Republic — the country’s first experiment with democracy — would come to an end. In November 1933, a report in The Times described the Nazis gathering in celebration: “Leaders Rejoice in Munich at Resurrection of the Movement ‘Killed’ There 10 Years Ago — Jubilant Over Steins.”

more here.

Saturday Poem

To the Child Watching His Grandmother Sew

The whir of the sewing machine fades

Like a faltering metronome.

If you can imagine each stitch

As a note,

You can hear a lone melody.

But you don’t know that yet.

You are too young, and it is too dark.

She’ll wait until the lights burn out,

And when she thinks you are asleep,

She’ll play that tune again.

One day, you’ll hear

Some love song on the radio

And understand.

The music crescendos—

The lights burn out, one by one,

And you remember

The needle’s steady hum:

The first love song you ever heard.

by Bradford Kimball

from Rattle Magazine, August 2023

How racial bias infiltrates health care

Pavan Amara in New Humanist:

The health service is a contradiction. It has been built on immigrant labour from conception to the present day. Walk into many NHS services, and you will find it is Black and Brown faces that are assessing, diagnosing and treating. Yet we find huge race-based health disparities, in maternity, mental health, Covid-19 deaths and more.

The health service is a contradiction. It has been built on immigrant labour from conception to the present day. Walk into many NHS services, and you will find it is Black and Brown faces that are assessing, diagnosing and treating. Yet we find huge race-based health disparities, in maternity, mental health, Covid-19 deaths and more.

Dr Annabel Sowemimo is a sexual and reproductive health registrar. She has spent years rotating through the health service as a junior doctor, working in everything from A&E to community clinics. Her father was a doctor, her grandmother a nursing auxiliary who moved from Nigeria to work in the then fledgling NHS. Divided is her debut. It is a mix of statistics, clinical vignettes and historic facts. Meticulously researched, the book attempts to explain how white scientists of the past have contributed to the racial biases that infiltrate health services today – from the eugenicists determined to prove that those with darker skin were substandard, to pioneers who developed treatments and diagnostic tools with white patients in mind.

More here.

These Bacteria Eat Plastic Waste—and Then Transform It Into Useful Products

Shelley Fan in Singularity Hub:

The first time I heard about the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, I thought it was a bad joke.

The first time I heard about the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, I thought it was a bad joke.

My incredulity soon turned to horror when I realized it’s real. The garbage patch, also known as the Pacific trash vortex, is a massive collection of debris in the North Pacific Ocean. Although made up of all sorts of human-generated waste, the main components are tiny pieces of microplastic. From straws to trash bags, we use an astonishing amount of plastic—which often ends up in delicate ocean (and other) ecosystems. According to the Center for Biological Diversity, a nonprofit organization for protecting endangered species based in Arizona, at current rates plastic is set to outweigh all fish in the ocean by 2050.

A new study wants to turn the tide with synthetic biology. By engineering genetic circuits into a bacterial “consortium,” the team reprogrammed two strains to not only destroy polluting plastics—but to also transform the toxic waste into useful biodegradable material. Environmentally friendly and versatile, these upcycled plastics can be used to manufacture foams, adhesives, or even nylon—all without further taxing the environment. The strategy isn’t just limited to the polyethylene terephthalate (PET)—one of the most common types of plastics—tested in the study, said the authors. “The underlying concept and strategies are potentially applicable…to other types of plastics” and could begin lighting the way toward “a sustainable bioeconomy.”

More here.

Friday, September 29, 2023

Cairo Song

Wiam El-Tamami in Granta:

Cairo. From my parents’ seventh-floor balcony I watch pigeons swoop and dive, as frantic as the city below them. Cairo is a relentless roar. A barrage of car horns, motors rushing and rumbling. Gangs of street dogs, barking, snarling, stalking the neighborhood. Scraping, drilling, grinding, vendors yelling out their wares, planes cleaving low through the sky. The air is an acrid haze, almost gritty, tinged with smoke.

Cairo. From my parents’ seventh-floor balcony I watch pigeons swoop and dive, as frantic as the city below them. Cairo is a relentless roar. A barrage of car horns, motors rushing and rumbling. Gangs of street dogs, barking, snarling, stalking the neighborhood. Scraping, drilling, grinding, vendors yelling out their wares, planes cleaving low through the sky. The air is an acrid haze, almost gritty, tinged with smoke.

There is a song about Cairo that my mother loves. It begins: ‘This is Cairo: the sorceress, the enchantress; the uproarious, the sleepless; the sheltering, the shameless.’ The whole song is an unfolding of love, of twisted tenderness, of impossibility – and all of it is true.

More here.

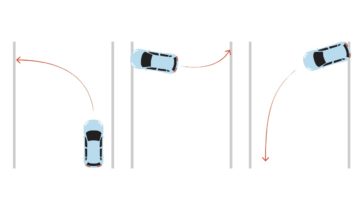

The spatial intuition behind a three-point turn offers an on-ramp to a century-old geometry problem

Patrick Honner in Quanta:

There’s a fun math problem here about how much space you need to turn your car around, and mathematicians have been working on an idealized version of it for over 100 years. It started in 1917 when the Japanese mathematician Sōichi Kakeya posed a problem that sounds a little like our traffic jam. Suppose you’ve got an infinitely thin needle of length 1. What’s the area of the smallest region in which you can turn the needle 180 degrees and return it to its original position? This is known as Kakeya’s needle problem, and mathematicians are still studying variations of it. Let’s take a look at the simple geometry that makes Kakeya’s needle problem so interesting and surprising.

There’s a fun math problem here about how much space you need to turn your car around, and mathematicians have been working on an idealized version of it for over 100 years. It started in 1917 when the Japanese mathematician Sōichi Kakeya posed a problem that sounds a little like our traffic jam. Suppose you’ve got an infinitely thin needle of length 1. What’s the area of the smallest region in which you can turn the needle 180 degrees and return it to its original position? This is known as Kakeya’s needle problem, and mathematicians are still studying variations of it. Let’s take a look at the simple geometry that makes Kakeya’s needle problem so interesting and surprising.

More here.

A Chinese Bubble Long in the Making

Yi Fuxian at Project Syndicate:

China’s property sector is the largest asset class in the world – larger even than the US equity or bond market. But there are growing fears that it is a bubble poised to burst. Already, the heavily indebted Chinese property giant Evergrande has filed for bankruptcy protection in the United States, and the real-estate developer Country Garden is battling a liquidity crisis. The failure of either, or both, could well trigger a financial crisis.

China’s property sector is the largest asset class in the world – larger even than the US equity or bond market. But there are growing fears that it is a bubble poised to burst. Already, the heavily indebted Chinese property giant Evergrande has filed for bankruptcy protection in the United States, and the real-estate developer Country Garden is battling a liquidity crisis. The failure of either, or both, could well trigger a financial crisis.

But why did a property bubble emerge in the first place? Like so many other problems in China today, this one can be traced back to the one-child policy that the government adopted in 1980 – a decision that would fundamentally reshape the country’s economic, political, and diplomatic trajectory.

More here.

N.W.A. – Straight Outta Compton

Why Boredom Matters: Education, Leisure, and the Quest for a Meaningful Life

Elizabeth Corey in First Things:

Conservative commentators have long bemoaned the proliferation of “studies” fields in the university. Women’s and gender studies are well known, but now students can take courses in topics as unusual as “surf studies” and “fat studies.” Given all the boring lectures that undergraduates have endured throughout the ages, it’s amusing to note that this list now includes “boredom studies,” for which there is even a journal—the Journal of Boredom Studies. Anyone who has ever attended an academic conference will find some humor in its call for papers: “Submit a proposal for the 5th boredom conference.”

Conservative commentators have long bemoaned the proliferation of “studies” fields in the university. Women’s and gender studies are well known, but now students can take courses in topics as unusual as “surf studies” and “fat studies.” Given all the boring lectures that undergraduates have endured throughout the ages, it’s amusing to note that this list now includes “boredom studies,” for which there is even a journal—the Journal of Boredom Studies. Anyone who has ever attended an academic conference will find some humor in its call for papers: “Submit a proposal for the 5th boredom conference.”

Much of this literature runs to the mundane or quantitative, but Kevin Hood Gary’s insightful book reflects his immersion in theology, philosophy, and literature. This is really a book about liberal education, as indicated by its subtitle: “Education, Leisure, and the Quest for a Meaningful Life.” If boredom is the problem, Gary argues, then the solution is learning how to be leisurely, in the classical sense.

More here.

Assembloids Unlock the Roles of Key Neurodevelopment Disease Genes

Aparna Nathan in The Scientist:

Brain development is a carefully choreographed dance. Neurons develop specialized functions and, in small hops, move through the brain to get into the correct position. The chemical signals coursing through the resulting network allow animals to think, feel, and live. In neurodevelopmental disorders (NDD), however, hundreds of mutations in the DNA can interrupt this process. But scientists still do not know how each of these mutations interrupts the neurons’ precise differentiation or migration patterns. Studying these defects directly in embryos or newborns is too dangerous, and other animal models may deviate from human development.

Brain development is a carefully choreographed dance. Neurons develop specialized functions and, in small hops, move through the brain to get into the correct position. The chemical signals coursing through the resulting network allow animals to think, feel, and live. In neurodevelopmental disorders (NDD), however, hundreds of mutations in the DNA can interrupt this process. But scientists still do not know how each of these mutations interrupts the neurons’ precise differentiation or migration patterns. Studying these defects directly in embryos or newborns is too dangerous, and other animal models may deviate from human development.

In a new study published in Nature, Sergiu Pașca, a neuroscientist at Stanford University, and his team combined assembloid technology with CRISPR gene editing to determine the role of neurodevelopmental disease genes during typical brain development and the mayhem that ensues when they are missing.

More here.

Paul Dirac – Quantum Mechanics Lecture

On The Thai Elections

Pavin Chachavalpongpun at n+1:

I WAS AMONG MANY THAIS who celebrated the outcome of the federal elections this May, in which the Move Forward Party won the most seats in the House of Representatives—151 out of a possible 500 contested. My happiness was political, but also personal. The verdict made it seem that I could return to my home country, from which I’ve been banned since the 2014 coup, when the military and monarchy combined to overthrow Thailand’s last democratically elected government, led by Yingluck Shinawatra. My crime then was violating Article 112 of the Criminal Code, also known as lèse-majesté law, which stipulates that anyone defaming the monarchy could be imprisoned for up to fifteen years. I have long been a critic of the Thai conservative establishment, in particular the monarchy. As my following on social media grew, my writing and public statements struck the establishment as a threat. In the aftermath of the 2014 coup, the junta summoned me twice for “attitude adjustment.” I rejected the summons. Then they issued a warrant for my arrest and revoked my passport, forcing me to apply for a refugee status with Japan, where I have since been residing and teaching at Kyoto University. One of the Move Forward Party’s main campaign promises was to reform Article 112. For a few months this summer, then, it seemed my exile was set to end.

I WAS AMONG MANY THAIS who celebrated the outcome of the federal elections this May, in which the Move Forward Party won the most seats in the House of Representatives—151 out of a possible 500 contested. My happiness was political, but also personal. The verdict made it seem that I could return to my home country, from which I’ve been banned since the 2014 coup, when the military and monarchy combined to overthrow Thailand’s last democratically elected government, led by Yingluck Shinawatra. My crime then was violating Article 112 of the Criminal Code, also known as lèse-majesté law, which stipulates that anyone defaming the monarchy could be imprisoned for up to fifteen years. I have long been a critic of the Thai conservative establishment, in particular the monarchy. As my following on social media grew, my writing and public statements struck the establishment as a threat. In the aftermath of the 2014 coup, the junta summoned me twice for “attitude adjustment.” I rejected the summons. Then they issued a warrant for my arrest and revoked my passport, forcing me to apply for a refugee status with Japan, where I have since been residing and teaching at Kyoto University. One of the Move Forward Party’s main campaign promises was to reform Article 112. For a few months this summer, then, it seemed my exile was set to end.

more here.