Kate Briggs at The Paris Review:

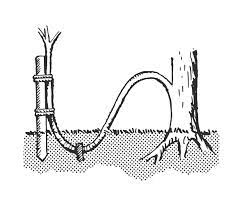

Marcottage could be a possible metaphor for translation. This work of provoking what plants, and perhaps also books, already know how to do, what in fact they most deeply want to do: actively creating the conditions for a new plant to root at some distance from the original, and there live separately: a “daughter-work” robust enough in its new context to throw out runners of its own, in unexpected directions, causing the network of interrelations to grow and complexify.

Marcottage could be a possible metaphor for translation. This work of provoking what plants, and perhaps also books, already know how to do, what in fact they most deeply want to do: actively creating the conditions for a new plant to root at some distance from the original, and there live separately: a “daughter-work” robust enough in its new context to throw out runners of its own, in unexpected directions, causing the network of interrelations to grow and complexify.

For me, marcottage is a way to make sense of my own translations of Barthes’s lecture courses. Officially, there have been two—two translations into English of two volumes of lecture notes published in French more than a decade ago: The Preparation of the Novel and How to Live Together. But to my mind, there have really been four: two further books, translations in a more expanded sense. This Little Art, my long essay that stays close to Barthes’s late work, frequently citing it, renarrating it, making an adjacent space to keep thinking with it.

more here.

Mustafa Suleyman, a co-founder of DeepMind and former vice president for AI products and policy at Google, offers some deep thoughts in his just-released book, “The Coming Wave: Technology, Power and the 21st Century’s Greatest Dilemma” (written with Michael Bhaskar).

Mustafa Suleyman, a co-founder of DeepMind and former vice president for AI products and policy at Google, offers some deep thoughts in his just-released book, “The Coming Wave: Technology, Power and the 21st Century’s Greatest Dilemma” (written with Michael Bhaskar). Evidence of continuities between animal communication and human language continued to mount. The sequencing of the Neanderthal genome in 2010 suggested that we hadn’t significantly diverged from that lineage, as the theory of a “human revolution” posited. On the contrary, Neanderthal genes and those of other ancient hominins persisted in the modern human genome, evidence of how intimately we were entangled. In 2014, Jarvis found that the

Evidence of continuities between animal communication and human language continued to mount. The sequencing of the Neanderthal genome in 2010 suggested that we hadn’t significantly diverged from that lineage, as the theory of a “human revolution” posited. On the contrary, Neanderthal genes and those of other ancient hominins persisted in the modern human genome, evidence of how intimately we were entangled. In 2014, Jarvis found that the  Surgeons in Baltimore have transplanted the heart of a genetically altered pig into a man with terminal heart disease who had no other hope for treatment, the University of Maryland Medical Center announced on Friday. It is the

Surgeons in Baltimore have transplanted the heart of a genetically altered pig into a man with terminal heart disease who had no other hope for treatment, the University of Maryland Medical Center announced on Friday. It is the  Of all the forms of human intellect that one might expect

Of all the forms of human intellect that one might expect  It is Mumbai in November, which is to say: hot.

It is Mumbai in November, which is to say: hot. In an attempt to address climate change and other environmental problems, governments are increasingly turning to economic solutions. The underlying message is clear: capitalism might have created the problem, but capitalism can solve it. Adrienne Buller, a Senior Fellow with progressive think tank Common Wealth, is, to put it mildly, sceptical of this. From carbon credits to biodiversity offsets, she unmasks these policies for the greenwashing that they are. The Value of a Whale is a necessary corrective that is as eye-opening as it is shocking.

In an attempt to address climate change and other environmental problems, governments are increasingly turning to economic solutions. The underlying message is clear: capitalism might have created the problem, but capitalism can solve it. Adrienne Buller, a Senior Fellow with progressive think tank Common Wealth, is, to put it mildly, sceptical of this. From carbon credits to biodiversity offsets, she unmasks these policies for the greenwashing that they are. The Value of a Whale is a necessary corrective that is as eye-opening as it is shocking. The past few years have seen an abundance of works of popular science about a variety of human beings who once inhabited Eurasia: “Neanderthals”. They died out, it appears, 40,000 years ago. That number – 40,000 – is as totemic to Neanderthal specialists as that better known figure, 65 million, is to dinosaur fanciers.

The past few years have seen an abundance of works of popular science about a variety of human beings who once inhabited Eurasia: “Neanderthals”. They died out, it appears, 40,000 years ago. That number – 40,000 – is as totemic to Neanderthal specialists as that better known figure, 65 million, is to dinosaur fanciers. To understand the origins of any franchise, look first to rights—who owns the intellectual property, how it is managed, and where the revenue generated from its exploitation is set to flow.

To understand the origins of any franchise, look first to rights—who owns the intellectual property, how it is managed, and where the revenue generated from its exploitation is set to flow. There are five fundamental operations in mathematics,” the German mathematician Martin Eichler supposedly said. “Addition, subtraction, multiplication, division and modular forms.”

There are five fundamental operations in mathematics,” the German mathematician Martin Eichler supposedly said. “Addition, subtraction, multiplication, division and modular forms.” Huda Dahbour was 35 years old when she moved with her husband and three children to the West Bank in September 1995. It was the second anniversary of the Oslo accords, which established pockets of Palestinian self-government in the occupied territories. Jerusalem was still relatively open when they arrived in East Sawahre, a neighbourhood just outside the areas of Jerusalem that

Huda Dahbour was 35 years old when she moved with her husband and three children to the West Bank in September 1995. It was the second anniversary of the Oslo accords, which established pockets of Palestinian self-government in the occupied territories. Jerusalem was still relatively open when they arrived in East Sawahre, a neighbourhood just outside the areas of Jerusalem that

In The Odyssey, Odysseus and his crew are forced to navigate a strait bounded by two equally dangerous obstacles: Scylla, a six-headed sea serpent, and Charybdis, an underwater horror that sucks down ships through a massive whirlpool. Judging Charybdis to be a greater danger to the crew as a whole, Odysseus orders his crew to try and pass through on Scylla’s side. They make it, but six sailors are eaten in the crossing. In their new book Tyranny of the Minority, Harvard political scientists Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt — the authors of How Democracies Die — argue America’s founders faced an analogous problem: navigating between two types of dictatorship that threatened to devour the new country.

In The Odyssey, Odysseus and his crew are forced to navigate a strait bounded by two equally dangerous obstacles: Scylla, a six-headed sea serpent, and Charybdis, an underwater horror that sucks down ships through a massive whirlpool. Judging Charybdis to be a greater danger to the crew as a whole, Odysseus orders his crew to try and pass through on Scylla’s side. They make it, but six sailors are eaten in the crossing. In their new book Tyranny of the Minority, Harvard political scientists Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt — the authors of How Democracies Die — argue America’s founders faced an analogous problem: navigating between two types of dictatorship that threatened to devour the new country. A strange, immortal tube-shaped animal has been discovered to regenerate a whole new body from only its mouth to avoid getting old. This creature, named Hydractinia symbiolongicarpus, a tiny invertebrate that lives on the shells of crabs, is usually immune to aging altogether, but was found to use aging within its body to grow an entirely new body, a study published in the

A strange, immortal tube-shaped animal has been discovered to regenerate a whole new body from only its mouth to avoid getting old. This creature, named Hydractinia symbiolongicarpus, a tiny invertebrate that lives on the shells of crabs, is usually immune to aging altogether, but was found to use aging within its body to grow an entirely new body, a study published in the