In Dissent, first Joshua Leifer:

In the face of this slaughter, parts of the Anglophone left have reacted with shocking inhumanity. Progressive journalists proclaimed “glory” to the Hamas fighters or announced a day of “celebration.” Lawyers who make their careers criticizing Israel’s violations of international law contorted themselves in defense of Hamas’s war crimes. A prominent writer cruelly tweeted, “what did y’all think decolonization meant? vibes? essays? losers.” Many others, including numerous academics, echoed her implication that this—the massacre of innocent men, women, children, the elderly—was the answer. “Decolonization is not a metaphor,” they declared in a furious chorus. A Yale professor, in a tweet which she later deleted, asserted that a woman taken hostage at the rave was a legitimate target because she had served in the army. A piece published in n+1 dismissed “smarmy moralizing about civilian deaths.” At a protest, briefly endorsed by the Democratic Socialists of America, under the banner, “All Out for Palestine,” a speaker grinningly described Hamas’s attack on the rave—“until the resistance came in electrified hang gliders and took at least several dozen hipsters,” he said—to a cheering crowd.

Winant replies:

One way of understanding Israel that I think should not be controversial is to say that it is a machine for the conversion of grief into power. The Zionist dream, born initially from the flames of pogroms and the romantic nationalist aspirations so common to the nineteenth century, became real in the ashes of the Shoah, under the sign “never again.” Commemoration of horrific violence done to Jews, as we all know, is central to what Israel means and the legitimacy that the state holds—the sword and shield in the hands of the Jewish people against reoccurrence. Anyone who has spent time in synagogues anywhere in the world, much less been in Israel for Yom HaShoah or visited Yad Vashem, can recognize this tight linkage between mourning and statehood.

This, on reflection, is a hideous fact. For what it means is that it is not possible to publicly grieve an Israeli Jewish life lost to violence without tithing ideologically to the IDF—whether you like it or not.

Leifer’s response here:

Winant writes “that it is not possible to publicly grieve an Israeli Jewish life lost to violence without tithing ideologically to the IDF—whether you like it or not.” Such a statement is a cruel abstraction, possible only from myopic remove, that misses how real, living Israelis and Palestinians are responding to this moment. It is not very hard to find examples that disprove this facile assertion. Here’s one: on Thursday, Ayman Odeh, who chairs the Arab-Jewish socialist party Hadash, delivered a speech to Israel’s Knesset. Odeh has felt the pain of Israeli apartheid on his own flesh; he has been wounded by its armed forces; he has devoted his life to resisting Israel’s abuses. And yet, as a Palestinian Arab and socialist leader, he was still able to say the following: “There is nothing in the world, not even the cursed occupation, that justifies the killing of innocent civilians.” If Odeh can manage this—under the boot of Israeli oppression, despite calls by Israeli rightists for his deportation and for genocide—then surely Winant and others on the Anglophone anti-imperialist left can, too.

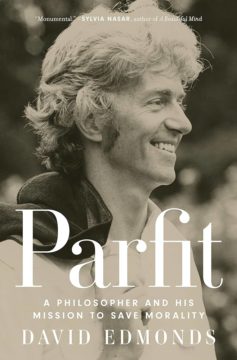

The subtitle of David Edmonds’s biography of the English philosopher Derek Parfit (1942-2017) is liable to raise more than a few eyebrows. Surely a mission to save morality is something only a God-like being could take on. And since God is dead, or rather has ceased to be believable, the prospect of rescuing morality must have vanished too. So is the subtitle to suggest that Parfit really was blessed with superhuman powers? Or are we to read it ironically, perhaps as a satirical comment on one philosopher’s exaggerated view of his own importance?

The subtitle of David Edmonds’s biography of the English philosopher Derek Parfit (1942-2017) is liable to raise more than a few eyebrows. Surely a mission to save morality is something only a God-like being could take on. And since God is dead, or rather has ceased to be believable, the prospect of rescuing morality must have vanished too. So is the subtitle to suggest that Parfit really was blessed with superhuman powers? Or are we to read it ironically, perhaps as a satirical comment on one philosopher’s exaggerated view of his own importance?

Invisible Cities is built like a Boolean Truth Table. The mathematical table shows all possible combinations of inputs, and for each combination the output that the circuit will produce. It’s a logic operation. The categories we find in Invisible Cities – Hidden Cities, Cities and Desire, Cities and Memory, Thin Cities, Dead Cities, and so on – aren’t random. Once chosen, these “inputs” will reveal their “outputs”. Think of a Truth Table as including a column for each variable in the expression and a row for each possible combination of truth values (or cities in our case). Then add a column that shows the outcome of each set of values. That’s the dialogue between Marco Polo and Kublai Khan.

Invisible Cities is built like a Boolean Truth Table. The mathematical table shows all possible combinations of inputs, and for each combination the output that the circuit will produce. It’s a logic operation. The categories we find in Invisible Cities – Hidden Cities, Cities and Desire, Cities and Memory, Thin Cities, Dead Cities, and so on – aren’t random. Once chosen, these “inputs” will reveal their “outputs”. Think of a Truth Table as including a column for each variable in the expression and a row for each possible combination of truth values (or cities in our case). Then add a column that shows the outcome of each set of values. That’s the dialogue between Marco Polo and Kublai Khan. B

B An international team of scientists has mapped the human brain in much finer resolution than ever before. The

An international team of scientists has mapped the human brain in much finer resolution than ever before. The  During a public conversation with Salman Rushdie on stage in New York City, I asked if he had advice for postcolonial writers. Rushdie said he had a rule for young writers: “There must be no tropical fruits in the title. No mangoes, no guavas. None of those. Tropical animals are also problematic. Peacock, etc. Avoid that shit.” (More of that exchange is to be found

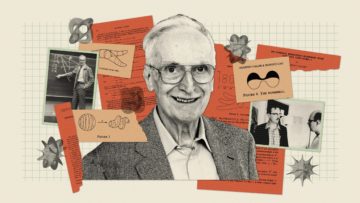

During a public conversation with Salman Rushdie on stage in New York City, I asked if he had advice for postcolonial writers. Rushdie said he had a rule for young writers: “There must be no tropical fruits in the title. No mangoes, no guavas. None of those. Tropical animals are also problematic. Peacock, etc. Avoid that shit.” (More of that exchange is to be found  Eugenio Calabi was known to his colleagues as an inventive mathematician — “transformatively original,” as his former student Xiuxiong Chen put it. In 1953, Calabi began to contemplate a class of shapes that nobody had ever envisioned before. Other mathematicians thought their existence was impossible. But a couple of decades later, these same shapes became extremely important in both math and physics. The results ended up having a far broader reach than anyone, including Calabi, had anticipated.

Eugenio Calabi was known to his colleagues as an inventive mathematician — “transformatively original,” as his former student Xiuxiong Chen put it. In 1953, Calabi began to contemplate a class of shapes that nobody had ever envisioned before. Other mathematicians thought their existence was impossible. But a couple of decades later, these same shapes became extremely important in both math and physics. The results ended up having a far broader reach than anyone, including Calabi, had anticipated. Two things are true: Israel must do something, and what it’s doing now is indefensible. So what’s the alternative?

Two things are true: Israel must do something, and what it’s doing now is indefensible. So what’s the alternative? “When the psychohistory of a people is marked by ongoing loss, when entire histories are denied, hidden, erased, documentation can become an obsession,” bell hooks writes in her book “

“When the psychohistory of a people is marked by ongoing loss, when entire histories are denied, hidden, erased, documentation can become an obsession,” bell hooks writes in her book “ As portents go, little could be more ominous than what took place on the evening of March 4, 1873, at the inaugural gala for President Ulysses S. Grant’s second term. A cavernous wooden structure had been built for the event. Hundreds of canaries had been brought in to serenade the guests, who were treated to a lavish spread of party food — partridges and oysters, boars’ heads and lobsters. But one crucial element had been bizarrely overlooked: The room wasn’t heated. The food started to freeze. By the time Grant and his entourage arrived, some of the canaries had keeled over, “falling like little lumps of frozen yellow fruit on the diners and dancers below.”

As portents go, little could be more ominous than what took place on the evening of March 4, 1873, at the inaugural gala for President Ulysses S. Grant’s second term. A cavernous wooden structure had been built for the event. Hundreds of canaries had been brought in to serenade the guests, who were treated to a lavish spread of party food — partridges and oysters, boars’ heads and lobsters. But one crucial element had been bizarrely overlooked: The room wasn’t heated. The food started to freeze. By the time Grant and his entourage arrived, some of the canaries had keeled over, “falling like little lumps of frozen yellow fruit on the diners and dancers below.” Adam Shatz on the war in Gaza in the LRB:

Adam Shatz on the war in Gaza in the LRB: Kevin P. Gallagher, Rishikesh Ram Bhandary, Rebecca Ray and Luma Ramos in Science Direct:

Kevin P. Gallagher, Rishikesh Ram Bhandary, Rebecca Ray and Luma Ramos in Science Direct: