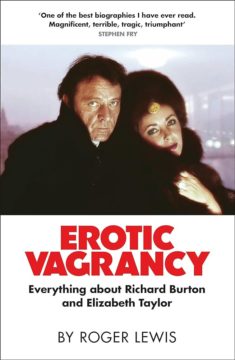

Anthony Quinn at The Guardian:

Here is the story of a wild folie à deux, or a dance of death in which both partners were tragically condemned to survive. Roger Lewis’s biography may not fulfil the promise of “everything” about Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor but it surely contains more than you could ever wish to know. “I make no apology for this being a visionary book,” he explains, sonorously, and often the reader does hear a singular voice at work – fearless, funny, provocative, acute, insistent. But oh, it’s exhausting too. Lewis, a Welshman, understands his native weakness: “garrulity”. Or, as Taylor was once overheard to say, as her husband drunkenly dominated another evening with Dylan Thomas recitals and lectures: “Does the man ever shut up?”

Here is the story of a wild folie à deux, or a dance of death in which both partners were tragically condemned to survive. Roger Lewis’s biography may not fulfil the promise of “everything” about Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor but it surely contains more than you could ever wish to know. “I make no apology for this being a visionary book,” he explains, sonorously, and often the reader does hear a singular voice at work – fearless, funny, provocative, acute, insistent. But oh, it’s exhausting too. Lewis, a Welshman, understands his native weakness: “garrulity”. Or, as Taylor was once overheard to say, as her husband drunkenly dominated another evening with Dylan Thomas recitals and lectures: “Does the man ever shut up?”

Perhaps only an outsize book could comprehend the excess, “the magnificent bad taste and greed and money” that became the keynote of the Burton-Taylor partnership. Lewis, disdaining standard biography as “bogus” and “an affair of ghosts”, adopts an impish, even jesterish approach – bouncing back and forth between eras, zooming in on minor characters, speculating on omissions and obfuscations in the official story.

more here.

If social media is to be believed,

If social media is to be believed,  About ten years ago, I decided to become a journalist, mainly because I liked writing. The reason I still am today is because I realised the potential impact my work can have on public debates, and the responsibilities that come with that. Being a journalist means influencing people’s opinions and tipping the balance on important social issues; it’s a job that should be taken very seriously.

About ten years ago, I decided to become a journalist, mainly because I liked writing. The reason I still am today is because I realised the potential impact my work can have on public debates, and the responsibilities that come with that. Being a journalist means influencing people’s opinions and tipping the balance on important social issues; it’s a job that should be taken very seriously. Existing healthcare institutions will be crushed as new business models with better and more efficient care emerge. Thousands of startups, as well as today’s data giants (Google, Apple, Microsoft, SAP, IBM, etc.) will all enter this lucrative $3.8 trillion healthcare industry with new business models that dematerialize, demonetize and democratize today’s bureaucratic and inefficient system.

Existing healthcare institutions will be crushed as new business models with better and more efficient care emerge. Thousands of startups, as well as today’s data giants (Google, Apple, Microsoft, SAP, IBM, etc.) will all enter this lucrative $3.8 trillion healthcare industry with new business models that dematerialize, demonetize and democratize today’s bureaucratic and inefficient system. In discussing Eliot’s work, it is tempting to pass over the messy details of her private life in delicate embarrassment. (That late-in-life marriage to John Cross, for example, is truly weird.) But Clare Carlisle’s excellent new book

In discussing Eliot’s work, it is tempting to pass over the messy details of her private life in delicate embarrassment. (That late-in-life marriage to John Cross, for example, is truly weird.) But Clare Carlisle’s excellent new book  Her essays are rich with unerasable moments, and as in her greatest works of fiction, they strike the intersecting point between tragedy and comedy. If she tugs on heart-strings in her essays—and most assuredly she does—she also demonstrates a clear awareness of the funny side of life.

Her essays are rich with unerasable moments, and as in her greatest works of fiction, they strike the intersecting point between tragedy and comedy. If she tugs on heart-strings in her essays—and most assuredly she does—she also demonstrates a clear awareness of the funny side of life. Each day brings a reminder of another threat to our peace and security. War, political instability and climate change send migrants and refugees across national borders. Cybercriminals hack networks of public and private institutions. Terrorists use trucks and planes as weapons.

Each day brings a reminder of another threat to our peace and security. War, political instability and climate change send migrants and refugees across national borders. Cybercriminals hack networks of public and private institutions. Terrorists use trucks and planes as weapons. A brain-inspired computer chip that could supercharge artificial intelligence (AI) by working faster with much less power has been developed by researchers at IBM in San Jose, California. Their massive NorthPole processor chip eliminates the need to frequently access external memory, and so performs tasks such as image recognition faster than existing architectures do — while consuming vastly less power.

A brain-inspired computer chip that could supercharge artificial intelligence (AI) by working faster with much less power has been developed by researchers at IBM in San Jose, California. Their massive NorthPole processor chip eliminates the need to frequently access external memory, and so performs tasks such as image recognition faster than existing architectures do — while consuming vastly less power.

I grew up around pumpkins. My dad grew big ones that were 80- or 100-pounders, and I always thought it was neat. Every kid loves pumpkins. We would also go to the state fair and see the giant pumpkins there, and I thought, “That’s kind of cool. I want to grow one.” When I was 14, I grew a 470-pounder. That was three decades ago, and I’ve been growing pumpkins ever since. I’m just now starting to get the hang of it. I didn’t even win a contest until 2020, but that year, I set the North American record with a

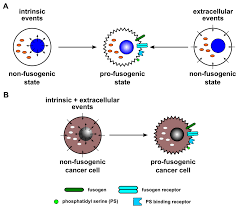

I grew up around pumpkins. My dad grew big ones that were 80- or 100-pounders, and I always thought it was neat. Every kid loves pumpkins. We would also go to the state fair and see the giant pumpkins there, and I thought, “That’s kind of cool. I want to grow one.” When I was 14, I grew a 470-pounder. That was three decades ago, and I’ve been growing pumpkins ever since. I’m just now starting to get the hang of it. I didn’t even win a contest until 2020, but that year, I set the North American record with a  Fusion among different cell populations represents a rare process that is mediated by both intrinsic and extracellular events. Cellular hybrid formation is relayed by orchestrating tightly regulated signaling pathways that can involve both normal and neoplastic cells. Certain important cell merger processes are often required during distinct organismal and tissue development, including placenta and skeletal muscle. In a neoplastic environment, however, cancer cell fusion can generate new cancer hybrid cells.

Fusion among different cell populations represents a rare process that is mediated by both intrinsic and extracellular events. Cellular hybrid formation is relayed by orchestrating tightly regulated signaling pathways that can involve both normal and neoplastic cells. Certain important cell merger processes are often required during distinct organismal and tissue development, including placenta and skeletal muscle. In a neoplastic environment, however, cancer cell fusion can generate new cancer hybrid cells. People who dislike Vladimir Nabokov tend to find his dexterity stressful, like watching a circus performer juggle torches for hours. The solution to this is to chill out. It’s not your job to worry that an elective juggler is going to light his shorts on fire! Let the performer assess his own risks!

People who dislike Vladimir Nabokov tend to find his dexterity stressful, like watching a circus performer juggle torches for hours. The solution to this is to chill out. It’s not your job to worry that an elective juggler is going to light his shorts on fire! Let the performer assess his own risks! An imbalance of fungi in the gut could contribute to excessive inflammation in people with severe COVID-19 or long COVID. A study found that individuals with severe disease had elevated levels of a fungus that can activate the immune system and induce long-lasting changes.

An imbalance of fungi in the gut could contribute to excessive inflammation in people with severe COVID-19 or long COVID. A study found that individuals with severe disease had elevated levels of a fungus that can activate the immune system and induce long-lasting changes. It is now 1 p.m., Wednesday, October 18, and I am at home, in Tel Aviv. Eleven days have passed since the October 7 attack on Israel. At least 1,400 people were killed in one day, mostly civilians, and there are around 200 Israeli hostages held in the Gaza Strip. Israel has since launched its deadliest attack on Gaza so far: around 3,500 Gazans have been killed, about 1,000 of them children. Hamas still manages to fire rockets at Israel, mostly toward towns closer to Gaza, but some toward Tel Aviv. Every evening, between 7 and 9 p.m., sirens go off and we run to find shelter. During the day we can sometimes hear unidentified explosions in the distance. There are many ambulances and police sirens; helicopters and fighter jets pass overhead, and there’s a constant sound of drones hovering over the city, to what purpose we do not know. Most stores are closed shut. Many restaurants and cafés have been transformed into supply centers from which food and equipment are delivered by volunteers across the country to soldiers, to survivors of the attack, and to residents from towns that have been evacuated. At night, a few bars open. They are half empty, the patrons drink and speak softly. In normal days, the city is packed and vibrant till late into the night. Around midnight, I go out to the balcony or take a stroll in the vacant streets. Everywhere the quiet is breathless.

It is now 1 p.m., Wednesday, October 18, and I am at home, in Tel Aviv. Eleven days have passed since the October 7 attack on Israel. At least 1,400 people were killed in one day, mostly civilians, and there are around 200 Israeli hostages held in the Gaza Strip. Israel has since launched its deadliest attack on Gaza so far: around 3,500 Gazans have been killed, about 1,000 of them children. Hamas still manages to fire rockets at Israel, mostly toward towns closer to Gaza, but some toward Tel Aviv. Every evening, between 7 and 9 p.m., sirens go off and we run to find shelter. During the day we can sometimes hear unidentified explosions in the distance. There are many ambulances and police sirens; helicopters and fighter jets pass overhead, and there’s a constant sound of drones hovering over the city, to what purpose we do not know. Most stores are closed shut. Many restaurants and cafés have been transformed into supply centers from which food and equipment are delivered by volunteers across the country to soldiers, to survivors of the attack, and to residents from towns that have been evacuated. At night, a few bars open. They are half empty, the patrons drink and speak softly. In normal days, the city is packed and vibrant till late into the night. Around midnight, I go out to the balcony or take a stroll in the vacant streets. Everywhere the quiet is breathless.