Hannah Gold in Harper’s Magazine:

It is difficult to predict when one will spend the night at a hotel in Newark, let alone three, and uncommon to agree to such a scenario willingly. If you live there already, you stay home. If you’re there for a professional engagement, your boss made you go. If your flight has been canceled, you go there as a last resort. Whereas, though I felt compelled to be there, I couldn’t point to an authority outside of myself that had forced my hand. The room had been booked a week in advance.

It is difficult to predict when one will spend the night at a hotel in Newark, let alone three, and uncommon to agree to such a scenario willingly. If you live there already, you stay home. If you’re there for a professional engagement, your boss made you go. If your flight has been canceled, you go there as a last resort. Whereas, though I felt compelled to be there, I couldn’t point to an authority outside of myself that had forced my hand. The room had been booked a week in advance.

I was in town, in March, for Philip Roth Unbound, a weekend-long festival hosted by the New Jersey Performing Arts Center, on the occasion of what would have been the author’s ninetieth birthday. A decade earlier, Roth had celebrated his eightieth in his hometown, with an elaborate party at the Newark Museum. He sat beside the podium and read from Sabbath’s Theater. “He was very much the author of his own birthday party,” David Remnick reported then, “and he seemed to enjoy it to the last.” This time, though, Roth’s allies and acolytes would need to put on the show all by themselves. What would it mean to reinscribe the decades of life and work within a context that the author has left behind?

More here.

Is it appropriate to call the three members of the sketch comedy group Please Don’t Destroy “boys”? They are grown men, in a sense, with jobs (Saturday Night Live writers) and, one assumes, growing 401(k)s. They’re in their mid-to-late 20s, six years into a career that started at New York University. Yet in other ways they are very obviously still tweens, gangly and silly, still figuring it all out. They’ve been known to sign emails to reporters “The Boys.” (This was revealed in

Is it appropriate to call the three members of the sketch comedy group Please Don’t Destroy “boys”? They are grown men, in a sense, with jobs (Saturday Night Live writers) and, one assumes, growing 401(k)s. They’re in their mid-to-late 20s, six years into a career that started at New York University. Yet in other ways they are very obviously still tweens, gangly and silly, still figuring it all out. They’ve been known to sign emails to reporters “The Boys.” (This was revealed in  “T

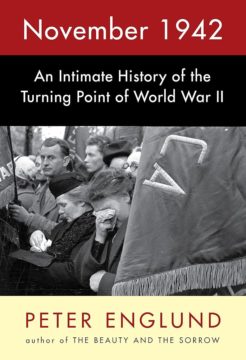

“T This format ensures an extraordinary — and bewildering — range of striking details. We learn that the bloated bodies of those who died in German U-boat attacks wash up along the coastline of Savannah, Ga.; that at the Treblinka death camp “there is almost always a jam when the door of one of the gas chambers is opened,” as the limbs of the corpses are so densely entangled; that when British soldiers in North Africa take five Italian prisoners, one of them happens to be a tenor from the Milan opera, and all five sing as they help with breakfast; that a Chinese civil servant tasked by the Nationalist government with collecting taxes from the starving population of Henan reports that people are eating bark and grass and selling their children for steamed rolls; that U.S. troops at Guadalcanal, desperate for alcohol of any kind, drink after-shave lotion “filtered through bread”; and that when a private with the Red Army northwest of Stalingrad peers out from his trench one night, he discovers a scene of terrible and staggering beauty — a freezing rain, reflecting the full moon’s light, has formed a shimmering veil over the landscape and the corpses of his dead companions.

This format ensures an extraordinary — and bewildering — range of striking details. We learn that the bloated bodies of those who died in German U-boat attacks wash up along the coastline of Savannah, Ga.; that at the Treblinka death camp “there is almost always a jam when the door of one of the gas chambers is opened,” as the limbs of the corpses are so densely entangled; that when British soldiers in North Africa take five Italian prisoners, one of them happens to be a tenor from the Milan opera, and all five sing as they help with breakfast; that a Chinese civil servant tasked by the Nationalist government with collecting taxes from the starving population of Henan reports that people are eating bark and grass and selling their children for steamed rolls; that U.S. troops at Guadalcanal, desperate for alcohol of any kind, drink after-shave lotion “filtered through bread”; and that when a private with the Red Army northwest of Stalingrad peers out from his trench one night, he discovers a scene of terrible and staggering beauty — a freezing rain, reflecting the full moon’s light, has formed a shimmering veil over the landscape and the corpses of his dead companions.

Charlotte Kent (Rail): Photography often gets discussed in terms of its stillness, of capturing or freezing a moment. But, in Where I Find Myself (2018) you wrote about watching Robert Frank and discovering photography’s motion: “that was at the heart of what I had seen: movements, the physicality of it, the timing, the positioning. I played third base, I knew about that kind of movement, it was energy in the service of the moment.” Can you describe how photography was about movement and this physicality? And then maybe also, how baseball comes into that?

Charlotte Kent (Rail): Photography often gets discussed in terms of its stillness, of capturing or freezing a moment. But, in Where I Find Myself (2018) you wrote about watching Robert Frank and discovering photography’s motion: “that was at the heart of what I had seen: movements, the physicality of it, the timing, the positioning. I played third base, I knew about that kind of movement, it was energy in the service of the moment.” Can you describe how photography was about movement and this physicality? And then maybe also, how baseball comes into that?

Many industries are betting that they will benefit from the anticipated quantum-computing revolution. Pharmaceutical companies and electric-vehicle manufacturers have begun to explore the use of quantum computers in chemistry simulations for drug discovery or battery development. Compared with state-of-the-art supercomputers, quantum computers are thought to more efficiently and accurately simulate molecules, which are inherently quantum mechanical in nature.

Many industries are betting that they will benefit from the anticipated quantum-computing revolution. Pharmaceutical companies and electric-vehicle manufacturers have begun to explore the use of quantum computers in chemistry simulations for drug discovery or battery development. Compared with state-of-the-art supercomputers, quantum computers are thought to more efficiently and accurately simulate molecules, which are inherently quantum mechanical in nature. As news of Hamas’s murderous October 7 surprise attack on Israel started to circulate in the global information space, so too did the propaganda. According to one estimate, the Israel-Hamas war sparked the highest volume of global propaganda—emanating not just from Israel, Palestine and other Middle Eastern countries but also from Russia, China, and Iran—that experts had ever seen. Even more so than after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in late February 2022, the outbreak of war between Israel and Hamas was springtime for propaganda.

As news of Hamas’s murderous October 7 surprise attack on Israel started to circulate in the global information space, so too did the propaganda. According to one estimate, the Israel-Hamas war sparked the highest volume of global propaganda—emanating not just from Israel, Palestine and other Middle Eastern countries but also from Russia, China, and Iran—that experts had ever seen. Even more so than after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in late February 2022, the outbreak of war between Israel and Hamas was springtime for propaganda.