Category: Recommended Reading

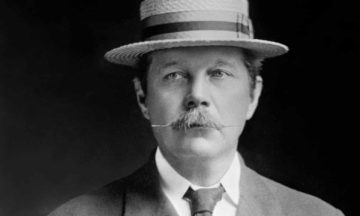

Arthur Conan Doyle secretly resented his Sherlock Holmes creation, says historian

Harriet Sherwood in The Guardian:

Arthur Conan Doyle secretly hated his creation Sherlock Holmes and blamed the cerebral detective character for denying him recognition as the author of highbrow historical fiction, according to the historian Lucy Worsley.

Arthur Conan Doyle secretly hated his creation Sherlock Holmes and blamed the cerebral detective character for denying him recognition as the author of highbrow historical fiction, according to the historian Lucy Worsley.

Doyle was catapulted from “obscurity to worldwide fame” after his crime stories began appearing in a magazine in 1891, Worsley writes in the Radio Times. Eleven years later he was awarded a knighthood. Yet “beneath the surface he was a discontented man”, according to Worsley. Conan Doyle struggled to find a publisher for his Sherlock stories after initially approaching the intellectual Cornhill magazine. “Only after they, and two others, rejected Mr Holmes, was he finally accepted by a fourth, much trashier, publisher. They said the work was exactly what they were looking for: ‘cheap fiction’.”

More here.

That Lingering ‘Meh’ Feeling Has a Name

Christina Caron in The New York Times:

By the time Amanda Stern was in her mid-40s, she no longer suffered from clinical depression. And her panic attacks, which had started in childhood, were mostly gone. But instead of feeling happier, she said, “I felt wallpapered in an endless, flat sadness.” Confused, she turned to her therapist, who suggested that she had dysthymia, a mild version of persistent depressive disorder, or P.D.D. Ms. Stern, an author based in New York City, often writes about mental health, but she had never heard the term. She soon realized that she had experienced dysthymia on and off for decades. “I am not suffering from it right now,” she added, “but I imagine I’ll live with it again.” She decided to write about it in her newsletter, How to Live, describing what it felt like to exist in a “constant state of ‘emptiness’” and sharing the tools that eventually helped her feel better. It is not well understood why some cases of depression persist, but The New York Times has asked experts to share what they know about P.D.D.

By the time Amanda Stern was in her mid-40s, she no longer suffered from clinical depression. And her panic attacks, which had started in childhood, were mostly gone. But instead of feeling happier, she said, “I felt wallpapered in an endless, flat sadness.” Confused, she turned to her therapist, who suggested that she had dysthymia, a mild version of persistent depressive disorder, or P.D.D. Ms. Stern, an author based in New York City, often writes about mental health, but she had never heard the term. She soon realized that she had experienced dysthymia on and off for decades. “I am not suffering from it right now,” she added, “but I imagine I’ll live with it again.” She decided to write about it in her newsletter, How to Live, describing what it felt like to exist in a “constant state of ‘emptiness’” and sharing the tools that eventually helped her feel better. It is not well understood why some cases of depression persist, but The New York Times has asked experts to share what they know about P.D.D.

More here.

Sunday, December 3, 2023

Sunday Poem

West Kennet Long Barrow

A cow rubs her ear against an oak tree

near the mouth of the Kennet River.

I am tired but Catrin takes me by my arm

up to the long barrow on the path winding

between fields of wheat. We stand where over

and over for a thousand years bones were placed

and then taken away. I have read that people

who know they will die in days sing differently

from those who will die in weeks. We know little

of these people whose bones rested here—how they hunted

with yew bows as long as themselves the animals

which were also their gods; or if they stopped

in their running, mouths open, gasping for breath

because of love; or sang in a particular way

close to death every day of their lives.

by Margaret Lloyd

from Open Field; Poems from Group 18

Open Field Press, Northampton Press, 2011

Shane MacGowan (1957 – 2023) Pogues Frontman

Jean Knight (1943 – 2023) Singer

Sandra Day O’Connor (1930 – 2023) Supreme Court Justice

When I Met the Pope

Patricia Lockwood in the London Review of Books:

The invitation said ‘black dress for Ladies’. ‘You’re not allowed to be whiter than him,’ my husband, Jason, instructs. ‘He has to be the whitest. And you cannot wear a hat because that is his thing.’

We are discussing the pope, who has woken one morning, at the age of 86, with a sudden craving to meet artists. An event has been proposed: a celebration in the Sistine Chapel on 23 June with the pope and two hundred honoured guests, to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the contemporary and modern art collection at the Vatican Museums. I am somehow one of these two hundred; either that, or it is a trap. ‘I think if you’re invited to meet the pope, you go,’ Jason tells me. ‘It will make a perfect ending.’ For what?

Uneasily, I pack a suitcase.

More here.

Google AI and robots join forces to build new materials

Mark Peplow in Nature:

An autonomous system that combines robotics with artificial intelligence (AI) to create entirely new materials has released its first trove of discoveries. The system, known as the A-Lab, devises recipes for materials, including some that might find uses in batteries or solar cells. Then, it carries out the synthesis and analyses the products — all without human intervention. Meanwhile, another AI system has predicted the existence of hundreds of thousands of stable materials, giving the A-Lab plenty of candidates to strive for in future.

An autonomous system that combines robotics with artificial intelligence (AI) to create entirely new materials has released its first trove of discoveries. The system, known as the A-Lab, devises recipes for materials, including some that might find uses in batteries or solar cells. Then, it carries out the synthesis and analyses the products — all without human intervention. Meanwhile, another AI system has predicted the existence of hundreds of thousands of stable materials, giving the A-Lab plenty of candidates to strive for in future.

Together, these advances promise to dramatically accelerate the discovery of materials for clean-energy technologies, next-generation electronics and a host of other applications.

More here.

Rediscovering the metaphysics of subsidiarity

Andrew Willard Jones in The Hedgehog Review:

The political right is in a state of upheaval. The old alliances have crumbled, and long-held truths have become empty truisms. The postwar conservatism of the Reagan administration and Newt Gingrich’s “Contract With America” is dead. All of this is so obvious that it hardly merits pointing out. Those who favor the status quo—the neoconservatives and neoliberals, to paint with broad strokes—are largely defecting to what passes for the center-left, leaving populists, nationalists, postliberals, neopagan Nietzscheans, and even the occasional libertarian to hash out the future of the “New Right.” An increasingly common thread among those factions is a rejection of old conservative commitments to the free market and the concomitant distinction between the public and private realms. We find ourselves in a place where it is just as valid to assert that everything is politics as it is to say that everything is economics or that everything is religion—or propaganda or marketing. The old categorical distinctions won’t hold.

What is missing is an awareness of real alternatives to our dominant political-economic order. Yet alternatives do exist, and here I propose that we consider—or more accurately, reconsider—one that is called subsidiarity as a source of concepts for building a viable economic and political theory that would in turn underwrite a genuine conservatism.

More here.

Bill Gates: How I Invest My Money in a Warming World

Bill Gates in the New York Times:

As we head into COP28, the annual global meeting on climate change underway in Dubai, there are two dominating schools of thought, both of which are wrong. One says the future is hopeless and our grandchildren are doomed to suffer on a burning planet. The other says we’re all going to be fine because we already have everything we need to solve climate change.

As we head into COP28, the annual global meeting on climate change underway in Dubai, there are two dominating schools of thought, both of which are wrong. One says the future is hopeless and our grandchildren are doomed to suffer on a burning planet. The other says we’re all going to be fine because we already have everything we need to solve climate change.

We’re not doomed, nor do we have all the solutions. What we do have is human ingenuity, our greatest asset. But to overcome climate change, we need rich individuals, companies and countries to step up to ensure green technologies are affordable for everyone, everywhere — including less wealthy countries that are large emitters, like China, India and Brazil.

Let’s start with what rich individuals, like me, can do to help.

More here.

The Inside Story of Microsoft’s Partnership with OpenAI

Charles Duhigg in The New Yorker:

At around 11:30 a.m. on the Friday before Thanksgiving, Microsoft’s chief executive, Satya Nadella, was having his weekly meeting with senior leaders when a panicked colleague told him to pick up the phone. An executive from OpenAI, an artificial-intelligence startup into which Microsoft had invested a reported thirteen billion dollars, was calling to explain that within the next twenty minutes the company’s board would announce that it had fired Sam Altman, OpenAI’s C.E.O. and co-founder. It was the start of a five-day crisis that some people at Microsoft began calling the Turkey-Shoot Clusterfuck.

At around 11:30 a.m. on the Friday before Thanksgiving, Microsoft’s chief executive, Satya Nadella, was having his weekly meeting with senior leaders when a panicked colleague told him to pick up the phone. An executive from OpenAI, an artificial-intelligence startup into which Microsoft had invested a reported thirteen billion dollars, was calling to explain that within the next twenty minutes the company’s board would announce that it had fired Sam Altman, OpenAI’s C.E.O. and co-founder. It was the start of a five-day crisis that some people at Microsoft began calling the Turkey-Shoot Clusterfuck.

Nadella has an easygoing demeanor, but he was so flabbergasted that for a moment he didn’t know what to say. He’d worked closely with Altman for more than four years and had grown to admire and trust him. Moreover, their collaboration had just led to Microsoft’s biggest rollout in a decade: a fleet of cutting-edge A.I. assistants that had been built on top of OpenAI’s technology and integrated into Microsoft’s core productivity programs, such as Word, Outlook, and PowerPoint. These assistants—essentially specialized and more powerful versions of OpenAI’s heralded ChatGPT—were known as the Office Copilots.

More here.

How to Exclaim!

Florence Hazrat in The Millions:

Noisy. Hysterical. Brash. The textual version of junk food. The selfie of grammar. The exclamation point attracts enormous (and undue) amounts of flak for its unabashed claim to presence in the name of emotion which some unkind souls interpret as egotistical attention-seeking. We’ve grown suspicious of feelings, particularly the big ones needing the eruption of a ! to relieve ourselves. This trend started sometime around 1900 when modernity began to mean functionality and clean straight lines (witness the sensible boxes of a Bauhaus building), rather than the “extra” mood of Victorian sensitivity or frilly playful Renaissance decorations.

Noisy. Hysterical. Brash. The textual version of junk food. The selfie of grammar. The exclamation point attracts enormous (and undue) amounts of flak for its unabashed claim to presence in the name of emotion which some unkind souls interpret as egotistical attention-seeking. We’ve grown suspicious of feelings, particularly the big ones needing the eruption of a ! to relieve ourselves. This trend started sometime around 1900 when modernity began to mean functionality and clean straight lines (witness the sensible boxes of a Bauhaus building), rather than the “extra” mood of Victorian sensitivity or frilly playful Renaissance decorations.

Things need to make sense, and the ! just doesn’t, subjective and subversive as it is, popping out from the uniform flow of words on the line. Since the triumphal conquering of smartphone technology and social media, the exclamation point finds fewer and fewer friends: We live in a digital village, chatting to one another from across the globe, and will use emotive social cues such as the exclamation point, and plenty of them. And because we just need to press down a thumbbbbbb to reproduce any character at nearly no cost, we’re more likely to flood the digital world with !!!!!!.

More here.

Saturday, December 2, 2023

Why exercise is key to living a long and healthy life

From Medical News Today:

In a study published in JAMA Internal MedicineTrusted Source in August 2023, Dr. del Pozo Cruz and his colleagues analyzed data from 500,705 participants followed up for a median period of 10 years to see how different forms of exercise related to a person’s mortality risk. The study looked at the effect of moderate aerobic physical activity, such as walking or gentle cycling, vigorous aerobic physical activity, such as running, and muscle-strengthening activity, like weight lifting. Its findings indicated that a balanced combination of all of these forms of exercise worked best for reducing mortality risk.

In a study published in JAMA Internal MedicineTrusted Source in August 2023, Dr. del Pozo Cruz and his colleagues analyzed data from 500,705 participants followed up for a median period of 10 years to see how different forms of exercise related to a person’s mortality risk. The study looked at the effect of moderate aerobic physical activity, such as walking or gentle cycling, vigorous aerobic physical activity, such as running, and muscle-strengthening activity, like weight lifting. Its findings indicated that a balanced combination of all of these forms of exercise worked best for reducing mortality risk.

More specifically, around 75 minutes of moderate aerobic exercise, plus more than 150 minutes of vigorous exercise, alongside at least a couple of strength training sessions per week were associated with a lower risk of all-cause mortality.

When it came to reducing the risk of death linked to cardiovascular disease specifically, Dr. del Pozo Cruz and his collaborators suggested combining a minimum of 150–225 minutes of moderate physical activity with around 75 minutes of vigorous exercise, and two or more strength training sessions per week.

More here.

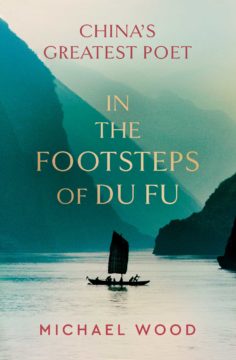

In The Footsteps Of Du Fu

John Simpson at The Guardian:

To our shame, few of us outside China know much about the country’s classical poetry. It doesn’t help that the way the names of leading poets are transliterated has changed so often. Many writers included in Ezra Pound’s groundbreaking collection Cathay, published in 1915, are unrecognisable by name today. Only a generation or so ago we called one of China’s greatest poets Li Po; nowadays we know him as Li Bai. And Li Bai’s friend and contemporary, the magnificent Du Fu, was until recently called Tu Fu in the west; different enough to put people who don’t speak Chinese off the scent in an online search.

To our shame, few of us outside China know much about the country’s classical poetry. It doesn’t help that the way the names of leading poets are transliterated has changed so often. Many writers included in Ezra Pound’s groundbreaking collection Cathay, published in 1915, are unrecognisable by name today. Only a generation or so ago we called one of China’s greatest poets Li Po; nowadays we know him as Li Bai. And Li Bai’s friend and contemporary, the magnificent Du Fu, was until recently called Tu Fu in the west; different enough to put people who don’t speak Chinese off the scent in an online search.

Even more elusive is the poetry itself. Du Fu, who Michael Wood, in his superb new book, unequivocally calls “China’s greatest poet” (some scholars may have other ideas about that, though personally I think Wood is right) wrote many of his finest poems in couplets of seven impressionistic characters each.

more here.

Prof Michael Wood Launches His New Book About Du Fu

The Story of Nature’s Toxins — From Spices to Vices

Robert Sullivan at the NY Times:

What doesn’t kill you might make you stronger. When it comes to nature’s toxins, they might even save your life (or at least blunt the sting of its finality). The distinction, as the evolutionary biologist Noah Whiteman explores in “Most Delicious Poison,” is all in the dosage.

What doesn’t kill you might make you stronger. When it comes to nature’s toxins, they might even save your life (or at least blunt the sting of its finality). The distinction, as the evolutionary biologist Noah Whiteman explores in “Most Delicious Poison,” is all in the dosage.

Take alcohol. Ethanol is likely born of plants’ evolutionary search for protection. Long before the first happy hour, yeast’s alcohol-making evolved as a means for the fungi residing in rotting fruit to survive oxygen deprivation. Ethanol thwarts most microbes; but yeast thrives, burning energy from sugar in oxygen’s absence. The same ethanol that might jump-start a party can, through addiction, mean the destruction of the liver — not to mention lives. Alcohol’s paradox, Whiteman writes, is tied to ethanol’s ability to mimic (or possibly bind to) gamma-aminobutyric acid — that is, the neurotransmitter our brains use to soften the nervous system’s activity.

more here.

Saturday Poem

Surfacing

Eight or nine years old,

I stood on the dock

over the dark, slatted river,

waiting for the sea cow

to surface. I didn’t know

the word manatee,

didn’t know men

had mistaken her

for a mermaid.

I only knew that if I waited

she would arrive.

The river smelled

part bracken, part small-

engine oil and kissed the wall

with a sound so sexual

I was glad no one was near

to be embarrassed for.

A chubby kid, I was sure

my way into the world

wouldn’t be through beauty.

And so, I had already begun

to run my fingers along

the fronts of words,

feeling for hinges.

The plastic bag of bread-ends

clammy in my hand,

sweat in my palm senseless

as hope—and then I saw her.

Ponderous, oblong, she wallowed

first, then spiraled up,

her face glamorous, human,

until she shed the glimmering

skin of water, broke the spell

with a comical snort.

I minded that she sloughed

her mystery off so easily,

though it comforted me too—

now I could give her bread

and watch her eat it.

But it was strange

to think she knew me.

Strange that she turned

from the soft weed

along the bank—every day

about this time—nosed

into the current, pushing

toward me.

by Trish Crapo

from Walk Through Paradise Backward

Slate Roof Press

Northfield, MA

This DeepMind AI Rapidly Learns New Skills Just by Watching Humans

Ed Gent in Singularity Hub:

Teaching algorithms to mimic humans typically requires hundreds or thousands of examples. But a new AI from Google DeepMind can pick up new skills from human demonstrators on the fly. One of humanity’s greatest tricks is our ability to acquire knowledge rapidly and efficiently from each other. This kind of social learning, often referred to as cultural transmission, is what allows us to show a colleague how to use a new tool or teach our children nursery rhymes. It’s no surprise that researchers have tried to replicate the process in machines. Imitation learning, in which AI watches a human complete a task and then tries to mimic their behavior, has long been a popular approach for training robots. But even today’s most advanced deep learning algorithms typically need to see many examples before they can successfully copy their trainers.

Teaching algorithms to mimic humans typically requires hundreds or thousands of examples. But a new AI from Google DeepMind can pick up new skills from human demonstrators on the fly. One of humanity’s greatest tricks is our ability to acquire knowledge rapidly and efficiently from each other. This kind of social learning, often referred to as cultural transmission, is what allows us to show a colleague how to use a new tool or teach our children nursery rhymes. It’s no surprise that researchers have tried to replicate the process in machines. Imitation learning, in which AI watches a human complete a task and then tries to mimic their behavior, has long been a popular approach for training robots. But even today’s most advanced deep learning algorithms typically need to see many examples before they can successfully copy their trainers.

When humans learn through imitation, they can often pick up new tasks after just a handful of demonstrations. Now, Google DeepMind researchers have taken a step toward rapid social learning in AI with agents that learn to navigate a virtual world from humans in real time. “Our agents succeed at real-time imitation of a human in novel contexts without using any pre-collected human data,” the researchers write in a paper in Nature Communications. “We identify a surprisingly simple set of ingredients sufficient for generating cultural transmission.”

More here.

Friday, December 1, 2023

James Salter’s Strange Career

Jeffrey Meyers at Salmagundi:

The English novelist Geoff Dyer remarked that “creative writing courses emphasise the importance of point-of-view and p.o.v. characters. Salter blows much of that stuff out of the water.” After the austere prose of his early war books he was no longer interested in traditional narrative and chronological structure, and used a radically different style and form in his third and fourth novels, A Sport and a Pastime and Light Years. The narrator in Sport is admittedly unreliable and cannot possibly have seen everything he describes. Salter told Phelps (punning in French on his name) that his sentence fragments—which suggest broken thoughts and incomplete speech—are “going to have many beautiful jumps, sauts, perhaps will be a ballet.” One puzzled critic noted that “Salter jumps the gap from one kind of time to another, from broad narrative time to tight episodic time, without a safety net, trusting the reader to follow him.” Salter also alienated readers by killing his main characters at the end of the novels: Connell in The Hunters, Cassada in Arm of Flesh, Dean in Sport, Nedra in Light Years.

The English novelist Geoff Dyer remarked that “creative writing courses emphasise the importance of point-of-view and p.o.v. characters. Salter blows much of that stuff out of the water.” After the austere prose of his early war books he was no longer interested in traditional narrative and chronological structure, and used a radically different style and form in his third and fourth novels, A Sport and a Pastime and Light Years. The narrator in Sport is admittedly unreliable and cannot possibly have seen everything he describes. Salter told Phelps (punning in French on his name) that his sentence fragments—which suggest broken thoughts and incomplete speech—are “going to have many beautiful jumps, sauts, perhaps will be a ballet.” One puzzled critic noted that “Salter jumps the gap from one kind of time to another, from broad narrative time to tight episodic time, without a safety net, trusting the reader to follow him.” Salter also alienated readers by killing his main characters at the end of the novels: Connell in The Hunters, Cassada in Arm of Flesh, Dean in Sport, Nedra in Light Years.

more here.