Category: Recommended Reading

Anna Cassel’s Prescient Paintings

Johanna Fateman at Bookforum:

IN 1912, THE SWEDISH ARTIST-CLAIRVOYANT Anna Cassel recorded the following message, crystal-clear instructions from a spirit guide, in her diary: “First, allow yourself to have dreams and then visions and colors and numbers, letters and images. Make a careful note of everything. It is of utmost importance to be thorough in your description.” Cassel was a lifelong friend of the spiritualist painter Hilma af Klint (and very likely more than a friend, for a time), as well as a close collaborator. In af Klint’s notebooks, Cassel’s group of 144 enthralling small paintings, her dutifully thorough description of a primordial story, transmitted to her from the astral plane, is referred to as “The Saga of the Rose.” The cycle was meant to serve as both a prayer book for the artists’ devout Christian-occult community (whose all-women initiates totaled just thirteen) and a history of the world. Discovered in the archive of the Swedish Anthroposophical Society in 2021, the sacred illustrations are reproduced in this solemnly beautiful clothbound book, its hushed design aligning with Cassel’s glyphic and celestial compositions. Fastidious and fervent, aware of trends in painting and Modernist decorative arts, Cassel favored botanically inspired lines, distilled geometries, and a crepuscular-or-witching hour palette to capture the strange wind and cold light of a particular metaphysical space.

more here.

Kurt Vonnegut’s House Is Not Haunted

Sophie Kemp at The Paris Review:

In August, I decided to drive to the house for the first time. I did this with my father, because he was the one who gave me Slaughterhouse-Five, and also because he’s now semi-retired and agreed in advance that it would be “funny,” and “cool,” to accompany his twenty-seven-year-old daughter on a “reporting trip” four miles down the road from his house. “Did you know he lived in Schenectady before you moved here?” I asked my father. “No, I don’t think so,” he responded. Out the window: my former elementary school and preschool, the Chinese Fellowship Bible Church, anonymous corporate campuses, new housing developments that when I was a kid were huge, empty fields.

In August, I decided to drive to the house for the first time. I did this with my father, because he was the one who gave me Slaughterhouse-Five, and also because he’s now semi-retired and agreed in advance that it would be “funny,” and “cool,” to accompany his twenty-seven-year-old daughter on a “reporting trip” four miles down the road from his house. “Did you know he lived in Schenectady before you moved here?” I asked my father. “No, I don’t think so,” he responded. Out the window: my former elementary school and preschool, the Chinese Fellowship Bible Church, anonymous corporate campuses, new housing developments that when I was a kid were huge, empty fields.

Vonnegut’s house, which I found by googling “Vonnegut’s house Schenectady NY,” is set directly overlooking Alplaus Creek, on a quiet side street. It is kind of in the woods. Lots of big trees on the street. The houses are old but not old. None of them are big. A few of them have big campers and ATVs out front, and the occasional snow mobile. Old cowboy boots used as planters and wind chimes. Vonnegut’s house is red, slightly set back from the road. It has seen better days, but it is kind of charmingly shabby, overgrown with plants spilling out of the gutters.

more here.

Tuesday Poem

Failing and Flying

Everyone forgets that Icarus also flew.

It’s the same when love comes to an end,

or the marriage fails and people say

they knew it was a mistake, that everybody

said it would never work. That she was

old enough to know better. But anything

worth doing is worth doing badly.

Like being there by that summer ocean

on the other side of the island while

love was fading out of her, the stars

burning so extravagantly those nights that

anyone could tell you they would never last.

Every morning she was asleep in my bed

like a visitation, the gentleness in her

like antelope standing in the dawn mist.

Each afternoon I watched her coming back

through the hot stoney field after swimming,

the sea light behind her and the huge sky

on the other side of that. Listened to her

while we ate lunch. How can they say

the marriage had failed? Like the people who

came back from Provence (when it was Provence)

and said it was pretty but the food was greasy.

I believe Icarus was not failing as he fell,

but just coming to the end of his triumph.

by Jack Gilbert

from Open Field-Poems from Group 18

Open Field Press, Northampton Ma. 2011

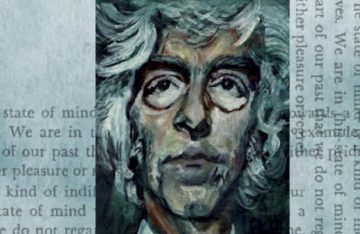

How ideas made Derek Parfit

Paul Nedelisky in The Hedgehog Review:

In 2007, the American philosopher Susan Hurley was dying of cancer. Twenty years earlier, she had been the first female fellow of All Souls College, Oxford. While there, she had been romantically involved with her philosopher colleague Derek Parfit. The romance faded but had turned into a deep friendship. Now, aware of her terminal illness, Hurley journeyed back to Oxford to say goodbye. Hurley and a mutual friend, Bill Ewald, asked Parfit to go to dinner with them. Parfit—by then an esteemed ethicist—refused to join them, protesting that he was too busy with his book manuscript, which concerned “what matters.” Saddened but undeterred, Hurley and Ewald stopped by Parfit’s rooms after dinner so that Hurley could still make her goodbye. Shockingly, Parfit showed them the door, again insisting that he could not spare the time. In truth, he was under no imminent or unalterable deadline. And even if he were, what is a few hours’ tardiness on a deadline compared to a final parting with an old friend? Was this man Parfit some kind of sociopath? Was this perhaps one of those rare but nevertheless possible momentary lapses of moral judgment? Or was he simply a wicked man?

In 2007, the American philosopher Susan Hurley was dying of cancer. Twenty years earlier, she had been the first female fellow of All Souls College, Oxford. While there, she had been romantically involved with her philosopher colleague Derek Parfit. The romance faded but had turned into a deep friendship. Now, aware of her terminal illness, Hurley journeyed back to Oxford to say goodbye. Hurley and a mutual friend, Bill Ewald, asked Parfit to go to dinner with them. Parfit—by then an esteemed ethicist—refused to join them, protesting that he was too busy with his book manuscript, which concerned “what matters.” Saddened but undeterred, Hurley and Ewald stopped by Parfit’s rooms after dinner so that Hurley could still make her goodbye. Shockingly, Parfit showed them the door, again insisting that he could not spare the time. In truth, he was under no imminent or unalterable deadline. And even if he were, what is a few hours’ tardiness on a deadline compared to a final parting with an old friend? Was this man Parfit some kind of sociopath? Was this perhaps one of those rare but nevertheless possible momentary lapses of moral judgment? Or was he simply a wicked man?

More here.

How Laws Evolved by Natural Selection

Peter DeScioli in Psychology Today:

Laws may seem unlikely to come from evolution. There are so many laws, and they differ so much across societies. This variation shows that natural selection did not install a single code of laws in the human mind. We do not have 10 commandments, or five or 20, etched into our minds, or else we would see the same code of laws repeated in society after society.

Laws may seem unlikely to come from evolution. There are so many laws, and they differ so much across societies. This variation shows that natural selection did not install a single code of laws in the human mind. We do not have 10 commandments, or five or 20, etched into our minds, or else we would see the same code of laws repeated in society after society.

But does this mean that human evolution has little to tell us about the origin of laws? Not at all. To see why, just compare laws to tools. Humans make countless tools, and tools vary tremendously across societies. Yet, it is well-understood that humans evolved adaptations to make and use tools. The human mind does not have a fixed set of blueprints for 10 or 20 tools.

More here.

Steven Weinberg and Richard Dawkins in Conversation, from 2008

A President’s Council on Artificial Intelligence

M. Anthony Mills in The New Atlantis:

Last month, President Joe Biden issued an executive order on artificial intelligence. Among the longest in recent decades and encompassing directives to dozens of federal agencies and certain companies, the order is a decidedly mixed bag. It shrinks back from the most aggressive proposals for federal intervention but leaves plenty for proponents of limited government to fret about. For instance, the order invokes the Defense Production Act — a law designed to assist private industry in providing necessary resources during a national security crisis — to regulate an emerging technology. This surely strains the law’s intent, not to mention allowing the executive branch to circumvent Congress.

Last month, President Joe Biden issued an executive order on artificial intelligence. Among the longest in recent decades and encompassing directives to dozens of federal agencies and certain companies, the order is a decidedly mixed bag. It shrinks back from the most aggressive proposals for federal intervention but leaves plenty for proponents of limited government to fret about. For instance, the order invokes the Defense Production Act — a law designed to assist private industry in providing necessary resources during a national security crisis — to regulate an emerging technology. This surely strains the law’s intent, not to mention allowing the executive branch to circumvent Congress.

Setting aside the merits or demerits of the order itself, however, it is worth stepping back to consider what this move by the White House tells us about the politics of AI — and in particular what it leaves out.

More here.

Why Do Evil and Suffering Exist? Religion Has One Answer, Literature Another

Ayana Mathis in The New York Times:

In the church of my childhood, we believed God’s angels battled demons in a war for our souls. This was not a metaphor. We were Pentecostals, though not strictly and not always. We weren’t picky about denomination; what mattered was belief in the redeeming blood of Christ, in the Bible literally interpreted and in God’s endless love. And evil. We believed in evil.

In the church of my childhood, we believed God’s angels battled demons in a war for our souls. This was not a metaphor. We were Pentecostals, though not strictly and not always. We weren’t picky about denomination; what mattered was belief in the redeeming blood of Christ, in the Bible literally interpreted and in God’s endless love. And evil. We believed in evil.

Sometimes evil was obvious — lies, betrayals, the misfortunes of innocents — but just as often it was camouflaged and seductive. It lurked in the card game, in the pop song and on the movie screen. It was in the allure of those things prohibited by religious or moral standards. The world was sunk in an evil passed down through Adam and Eve’s original sin and their fall from Eden.

I long ago abandoned this version of reality, but the questions it meant to address persist: Are the sensational evils that continue to plague us — murder and torture and its ilk — an expression of a (metaphorically) fallen world? Why these wars and more wars, these repeating atrocities of every stripe? How do we navigate a world beset by dark forces, and what do we do in the face of the suffering they cause?

More here.

At 33, I knew everything. At 69, I know something much more important

Anne Lamott in The Washington Post:

In many of Albert Bierstadt’s Western paintings, there is a darkness on one side, maybe a mountain or its shadow. Then toward the middle, animals graze or drink from a lake or stream. And then at the far right or in the sky, splashes of light lie like shawls across the shoulders of the mountains. The great darkness says to me what I often say to heartbroken friends — “I don’t know.”

In many of Albert Bierstadt’s Western paintings, there is a darkness on one side, maybe a mountain or its shadow. Then toward the middle, animals graze or drink from a lake or stream. And then at the far right or in the sky, splashes of light lie like shawls across the shoulders of the mountains. The great darkness says to me what I often say to heartbroken friends — “I don’t know.”

Is there meaning in the Maine shootings?

I don’t know. Not yet.

My white-haired husband said on our first date seven years ago that “I don’t know” is the portal to the richness inside us. This insight was one reason I agreed to a second date (along with his beautiful hands). It was a game-changer. Twenty years earlier, when my brothers and I were trying to take care of our mother in her apartment when she first had Alzheimer’s, we cried out to her gerontology nurse, “We don’t know if she can stay here, how to help her take her meds, how to get her to eat better since she forgets.” And the nurse said gently, “How could you know?”

This literally had not crossed our minds. We just thought we were incompetent. In the shadow of the mountain of our mother’s decline, we hardly knew where to begin. So we started where we were, in the not knowing.

More here.

Sunday, November 19, 2023

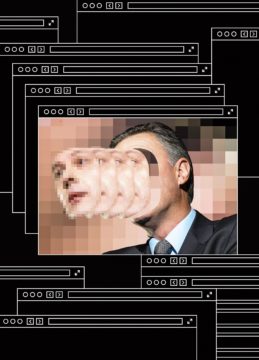

What the Doomsayers Get Wrong About Deepfakes

There’s a video of Gal Gadot having sex with her stepbrother on the internet.” With that sentence, written by the journalist Samantha Cole for the tech site Motherboard in December, 2017, a queasy new chapter in our cultural history opened. A programmer calling himself “deepfakes” told Cole that he’d used artificial intelligence to insert Gadot’s face into a pornographic video. And he’d made others: clips altered to feature Aubrey Plaza, Scarlett Johansson, Maisie Williams, and Taylor Swift.

There’s a video of Gal Gadot having sex with her stepbrother on the internet.” With that sentence, written by the journalist Samantha Cole for the tech site Motherboard in December, 2017, a queasy new chapter in our cultural history opened. A programmer calling himself “deepfakes” told Cole that he’d used artificial intelligence to insert Gadot’s face into a pornographic video. And he’d made others: clips altered to feature Aubrey Plaza, Scarlett Johansson, Maisie Williams, and Taylor Swift.A.S. Byatt (1936 – 2023) Critic, Novelist, Poet

Don Walsh (1931 – 2023) Oceanographer, Deep Sea Explorer

George Brown (1949 – 2023) Kool And The Gang Drummer

The Astonishing Behavior of Recursive Sequences

Alex Stone in Quanta Magazine:

In mathematics, simple rules can unlock universes of complexity and beauty. Take the famous Fibonacci sequence, which is defined as follows: It begins with 1 and 1, and each subsequent number is the sum of the previous two. The first few numbers are:

In mathematics, simple rules can unlock universes of complexity and beauty. Take the famous Fibonacci sequence, which is defined as follows: It begins with 1 and 1, and each subsequent number is the sum of the previous two. The first few numbers are:

1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34 …

Simple, yes, but this unassuming recipe gives rise to a pattern of far-reaching significance, one that appears to be woven into the very fabric of the natural world. It’s seen in the whorls of nautilus shells, the bones in our fingers, and the arrangement of leaves on tree branches. Its mathematical reach extends to geometry, algebra and probability, among other areas. Eight centuries since the sequence was introduced to the West — Indian mathematicians studied it long before Fibonacci — the numbers continue to attract the interest of researchers, a testament to how much mathematical depth can underlie even the most elementary number sequence.

More here.

Sunday Poem

How I was Put to Bed

It was in the small dark apartment,

its long hall leading to a dark

metal door which opened to yet

another hallway, then a corridor

down to the lit stage of a street—

wide noise, a day, the squint of it,

then darkness again, and

I am kissed and lowered onto

a bed with two pillows, boulders

covered by a forest green cotton spread.

Down I go into that field, that river

and green sky. The bed smells good

and quickly I inhale and fall

into sleep, into nothing, then my father,

hours later, carries me limp to

the gray velveteen couch so he and

my mother have somewhere to sleep.

I never woke under transport,

never knew how a day was manufactured—

my arms, legs, and eyes open to the living

room of yet another morning. So must it

have been with Eve waking in that

voluptuous garden, stunned, back

where she never remembered having started.

by Genie Zeiger

from Open Field

Open Field Press, 2011

Leading novelists on how AI could rewrite the future

Jeanette Winterson [and others] in The Guardian:

In my book of essays about life with AI – moving from Mary Shelley’s 1818 vision of a man-made humanoid to the possibilities of the metaverse – I describe AI not as artificial intelligence but alternative intelligence.

In my book of essays about life with AI – moving from Mary Shelley’s 1818 vision of a man-made humanoid to the possibilities of the metaverse – I describe AI not as artificial intelligence but alternative intelligence.

I am not thrilled with where Homo sapiens has landed us, and I believe we are at the point where we evolve or wipe out ourselves, and the planet. There is no reason to believe that the last 300,000 years mark us out as a species that is fully evolved. Our behaviour suggests the opposite. I would like to see a transhuman, eventually a post-human, future where intelligence and consciousness are no longer exclusively housed in a substrate made of meat. After all, that has been the promise of every world religion.

I was brought up in a strict religious household, and it intrigues me that for the first time since the Enlightenment, science and religion are asking the same question: is consciousness obliged to materiality? Religion has always said no. Scientific materialism has said yes. And now? It’s getting interesting.

More here.

On the Magic of Magnetic Force

Roma Agrawal at Literary Hub:

We have been through a radical shift in technology across just three generations of my family, and each step of the way has changed our lives dramatically, just as they did for society as a whole: allowing us to communicate with our loved ones, creating the world of instant news, changing the way we work, and altering the way we entertain and are entertained. But while a video call may seem a far cry from the telegram, all these forms of modern communication are based on the science of signals being sent from one distant point to another, almost instantaneously. And our ability to do that centers around magnets.

We have been through a radical shift in technology across just three generations of my family, and each step of the way has changed our lives dramatically, just as they did for society as a whole: allowing us to communicate with our loved ones, creating the world of instant news, changing the way we work, and altering the way we entertain and are entertained. But while a video call may seem a far cry from the telegram, all these forms of modern communication are based on the science of signals being sent from one distant point to another, almost instantaneously. And our ability to do that centers around magnets.

More here.

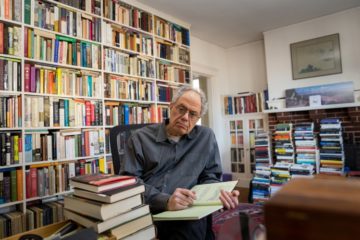

George Scialabba’s Prejudice for Progress

Sam Adler-Bell at Commonweal:

In an essay on the voluble New York intellectual Dwight Macdonald, George Scialabba cites Lionel Trilling’s assessment of Orwell, who, for Trilling, exemplified “the virtue of not being a genius, of fronting the world with nothing more than one’s simple, direct, undeceived intelligence, and a respect for the powers one does have, and the work one undertakes to do.”

In an essay on the voluble New York intellectual Dwight Macdonald, George Scialabba cites Lionel Trilling’s assessment of Orwell, who, for Trilling, exemplified “the virtue of not being a genius, of fronting the world with nothing more than one’s simple, direct, undeceived intelligence, and a respect for the powers one does have, and the work one undertakes to do.”

Much the same could be said of George Scialabba. For forty-four years, he has made a gift of his “direct, undeceived intelligence”—I would not say “simple”—to those fortunate readers who, as Richard Rorty once recommended, “stay on the lookout for [his] byline.”

Scialabba’s new collection, Only a Voice, contains twenty-eight previously published essays, the earliest from 1984, the latest (from this magazine) in 2021. They’re gathered here with a new introduction that takes up a perennial question for Scialabba—“What are intellectuals good for?”—and an apposite epigraph from Auden’s “September 1, 1939.”

More here.

The humble pocket has changed the way we equip ourselves to face the world

Virginia Postrel at Quillette:

Like printed books, perspective drawing, and double-entry bookkeeping, pockets were heralds of the modern era. In most times and places, people have either carried their money, combs, papers, and other small items in bags separate from their garments or tucked them into belts or sleeves. Integrated pockets are a product of European tailoring, which dates back only to the 14th century. They emerged when men’s breeches ballooned in the mid-1500s.

Like printed books, perspective drawing, and double-entry bookkeeping, pockets were heralds of the modern era. In most times and places, people have either carried their money, combs, papers, and other small items in bags separate from their garments or tucked them into belts or sleeves. Integrated pockets are a product of European tailoring, which dates back only to the 14th century. They emerged when men’s breeches ballooned in the mid-1500s.

Early pockets were bags sewn to the inside of the waistband and otherwise hanging loose. They were significantly larger than modern pockets—a rare surviving example from 1567 is a foot deep—and sometimes included drawstrings. Regardless of size, the critical change was that the pocket became part of the clothing and thus a more secure and intimate extension of the wearer.

More here.