Category: Recommended Reading

The Hidden Differences In How People Experience The World

Gary Lupyan at Aeon Magazine:

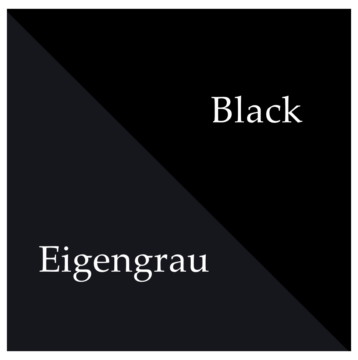

What is it about differences in imagery, inner speech, synaesthesia and memory that render them hidden? It is tempting to think that it’s because we don’t directly observe them. We can see that someone is a really fast runner. But having direct access only to our own reality, how are we to know what another person imagines when they think of an apple, or whether they hear a voice when they read? Still, while we can’t directly experience another person’s reality, we can compare notes by talking about it. Often, it’s remarkably easy: for #TheDress, we just needed to ask one another what colours we see. We can also ask whether letters always appear in colour (a grapheme-colour synaesthete will say yes; others will say no). People without imagery will tell you they cannot visualise an apple, and those without inner speech will say they do not have silent conversations with themselves. It is not actually difficult to discover these differences once we start systematically studying them.

What is it about differences in imagery, inner speech, synaesthesia and memory that render them hidden? It is tempting to think that it’s because we don’t directly observe them. We can see that someone is a really fast runner. But having direct access only to our own reality, how are we to know what another person imagines when they think of an apple, or whether they hear a voice when they read? Still, while we can’t directly experience another person’s reality, we can compare notes by talking about it. Often, it’s remarkably easy: for #TheDress, we just needed to ask one another what colours we see. We can also ask whether letters always appear in colour (a grapheme-colour synaesthete will say yes; others will say no). People without imagery will tell you they cannot visualise an apple, and those without inner speech will say they do not have silent conversations with themselves. It is not actually difficult to discover these differences once we start systematically studying them.

Paradoxically, although language is what allows us to compare notes and learn about differences between our subjective experiences, its power to abstract may also cause us to overlook these differences because the same word can mean many different things.

more here.

Absinthe Minded

at The New Criterion:

Baudelaire’s early suspicion that he had been born under a dark star seemed to be fulfilling itself. He considered becoming a monk but instead went to Belgium. “One becomes a Belgian through having sinned,” he quipped. “A Belgian is his own hell.” While walking to a church one day with the artist Félicien Rops, Baudelaire collapsed. Returning to Paris, he died in 1867 at the age of forty-six. The funeral was held in Montparnasse. Only sixty people showed up to honor the greatest poet France has ever created, but one of the mourners was Manet. Later, the journalist Victor Noir wrote, “in his last moments, his best friend was M. Manet; it was because the two natures understood each other so well.”

Baudelaire’s early suspicion that he had been born under a dark star seemed to be fulfilling itself. He considered becoming a monk but instead went to Belgium. “One becomes a Belgian through having sinned,” he quipped. “A Belgian is his own hell.” While walking to a church one day with the artist Félicien Rops, Baudelaire collapsed. Returning to Paris, he died in 1867 at the age of forty-six. The funeral was held in Montparnasse. Only sixty people showed up to honor the greatest poet France has ever created, but one of the mourners was Manet. Later, the journalist Victor Noir wrote, “in his last moments, his best friend was M. Manet; it was because the two natures understood each other so well.”

Around this time a young Parisian author and playwright, Henri Balesta, wrote a treatise Absinthe et Absintheurs (1860), which was probably (according to the pharmacologist Ronald K. Siegel) the first known book to record the socialization of absinthe abuse. Gradually, an anti-alcohol movement was growing in France as well as England.

more here.

Yoga nidra might be a path to better sleep and improved memory

From Phys.Org:

Practicing yoga nidra—a kind of mindfulness training—might improve sleep, cognition, learning, and memory, even in novices, according to a pilot study published in the open-access journal PLOS ONE on December 13 by Karuna Datta of the Armed Forces Medical College in India, and colleagues. After a two-week intervention with a cohort of novice practitioners, the researchers found that the percentage of delta-waves in deep sleep increased and that all tested cognitive abilities improved.

Practicing yoga nidra—a kind of mindfulness training—might improve sleep, cognition, learning, and memory, even in novices, according to a pilot study published in the open-access journal PLOS ONE on December 13 by Karuna Datta of the Armed Forces Medical College in India, and colleagues. After a two-week intervention with a cohort of novice practitioners, the researchers found that the percentage of delta-waves in deep sleep increased and that all tested cognitive abilities improved.

Unlike more active forms of yoga, which focus on physical postures, breathing, and muscle control, yoga nidra guides people into a state of conscious relaxation while they are lying down. While it has been reported to improve sleep and cognitive ability, those reports were based more on subjective measures than on objective data. The new study used objective polysomnographic measures of sleep and a battery of cognitive tests. Measurements were taken before and after two weeks of yoga nidra practice, which was carried out during the daytime using a 20-minute audio recording.

More here.

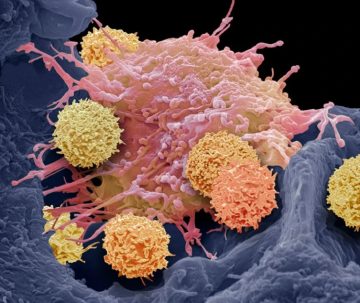

All the Carcinogens We Cannot See

Siddhartha Mukherjee in The New Yorker:

In the nineteen-seventies, Bruce Ames, a biochemist at Berkeley, devised a way to test whether a chemical might cause cancer. Various tenets of cancer biology were already well established. Cancer resulted from genetic mutations—changes in a cell’s DNA sequence that typically cause the cell to divide uncontrollably. These mutations could be inherited, induced by viruses, or generated by random copying errors in dividing cells. They could also be produced by physical or chemical agents: radiation, ultraviolet light, benzene. One day, Ames had found himself reading the list of ingredients on a package of potato chips, and wondering how safe the chemicals used as preservatives really were.

In the nineteen-seventies, Bruce Ames, a biochemist at Berkeley, devised a way to test whether a chemical might cause cancer. Various tenets of cancer biology were already well established. Cancer resulted from genetic mutations—changes in a cell’s DNA sequence that typically cause the cell to divide uncontrollably. These mutations could be inherited, induced by viruses, or generated by random copying errors in dividing cells. They could also be produced by physical or chemical agents: radiation, ultraviolet light, benzene. One day, Ames had found himself reading the list of ingredients on a package of potato chips, and wondering how safe the chemicals used as preservatives really were.

But how to catch a carcinogen? You could expose a rodent to a suspect chemical and see if it developed cancer; toxicologists had done so for generations. But that approach was too slow and costly to deploy on a wide enough scale. Ames—a limber fellow who was partial to wide-lapel tweed jackets and unorthodox neckties—had an idea. If an agent caused DNA mutations in human cells, he reasoned, it was likely to cause mutations in bacterial cells. And Ames had a way of measuring the mutation rate in bacteria, using fast-growing, easy-to-culture strains of salmonella, which he had been studying for a couple of decades. With a few colleagues, he established the assay and published a paper outlining the method with a bold title: “Carcinogens Are Mutagens.” The so-called Ames test for mutagens remains the standard lab technique for screening substances that may cause cancer.

More here.

40 Outstanding Winning Photos Of The International Photography Awards 2023

More here.

The (Often) Overlooked Experiment That Revealed the Quantum World

Zack Savitsky in Quanta:

Before Erwin Schrödinger’s cat was simultaneously dead and alive, and before pointlike electrons washed like waves through thin slits, a somewhat lesser-known experiment lifted the veil on the bewildering beauty of the quantum world. In 1922, the German physicists Otto Stern and Walther Gerlach demonstrated that the behavior of atoms was governed by rules that defied expectations — an observation that cemented the still-budding theory of quantum mechanics.

Before Erwin Schrödinger’s cat was simultaneously dead and alive, and before pointlike electrons washed like waves through thin slits, a somewhat lesser-known experiment lifted the veil on the bewildering beauty of the quantum world. In 1922, the German physicists Otto Stern and Walther Gerlach demonstrated that the behavior of atoms was governed by rules that defied expectations — an observation that cemented the still-budding theory of quantum mechanics.

“The Stern-Gerlach experiment is an icon — it’s an epochal experiment,” said Bretislav Friedrich, a physicist and historian at the Fritz Haber Institute in Germany who recently published a review and edited a book on the subject. “It was indeed one of the most important experiments in physics of all time.”

More here.

Sean Carroll, Nina Lanza, and Kevin Kelly: How should we be thinking about the future?

Beyond the Green Line: Imagining a Just Future

Julie E. Cooper in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

IN THE DAYS following Hamas’s brutal massacre on October 7, the atmosphere in Tel Aviv was tense and somber. As if seized by a collective depression, residents wandered around zombielike, unsure whether and how to conduct mundane transactions. Sirens blared periodically, warning us to take shelter from incoming missiles. While huddled in shelters and stairwells waiting for the “boom” that signals a missile interception, people scrolled frantically on their phones. Social media networks were inundated with macabre video clips—captured by the perpetrators’ body cameras—from the carnage on the southern border. In our stairwell, neighbors seemed evenly divided between those who could not look away from the gruesome images of murder, arson, kidnapping, rape, and mutilation, and those who—whether to honor the victims’ violated dignity or to shield themselves from the horror—refused to look.

More here.

Wednesday, December 13, 2023

How Shane MacGowan Became The Bard Of The Irish Diaspora

Brendan Ruberry at Commonweal:

MacGowan died last week at the age of sixty-five, and to many it seemed a small miracle that he lived as long as that. His fame as a drinker was almost as great as his fame as a songwriter and performer, and all that dissipation took a toll. For one thing, it could make him sound mean. In Julien Temple’s 2020 documentary, Crock of Gold: A Few Rounds With Shane MacGowan, we see him insult his wife and friends. He is in a wheelchair, frail, and white as a sheet, making his friend (and the film’s producer) Johnny Depp, only five years younger, seem like the very image of youthful vigor by contrast. “You can be a right bitch,” he tells his wife Victoria. “But you really are very, very nice. And beautiful.”

MacGowan died last week at the age of sixty-five, and to many it seemed a small miracle that he lived as long as that. His fame as a drinker was almost as great as his fame as a songwriter and performer, and all that dissipation took a toll. For one thing, it could make him sound mean. In Julien Temple’s 2020 documentary, Crock of Gold: A Few Rounds With Shane MacGowan, we see him insult his wife and friends. He is in a wheelchair, frail, and white as a sheet, making his friend (and the film’s producer) Johnny Depp, only five years younger, seem like the very image of youthful vigor by contrast. “You can be a right bitch,” he tells his wife Victoria. “But you really are very, very nice. And beautiful.”

He idolized hard-drinking writers like Flann O’Brien and Brendan Behan, whose apparition MacGowan meets in the song “Streams of Whiskey.”

more here.

Trances, Ecstasies, Raptures, and Levitations

Peter B. Kaufman at the LARB:

THIS PAST JULY, the University of Chicago’s National Opinion Research Center (NORC) and the Associated Press published the results of a May 2023 poll. Of the 1,680 American adults whom they interviewed (a representative sampling of the population at large), 69 percent said they believe in angels, 69 percent said they believe in heaven, 58 percent believe in hell, 56 percent in the existence of the devil, and 50 percent that spirits from the dead can communicate with the living. Reincarnation? The power of prayer? Astrology? Karma? Yoga as a spiritual practice? The idea that spiritual energy can be rooted in physical objects? Just six percent of us believe in none of these things. With this poll’s margin of error at plus or minus four points and other national polls over the years indicating much the same thing, it’s safe to say that 90 percent of all Americans today believe in something supernatural.

THIS PAST JULY, the University of Chicago’s National Opinion Research Center (NORC) and the Associated Press published the results of a May 2023 poll. Of the 1,680 American adults whom they interviewed (a representative sampling of the population at large), 69 percent said they believe in angels, 69 percent said they believe in heaven, 58 percent believe in hell, 56 percent in the existence of the devil, and 50 percent that spirits from the dead can communicate with the living. Reincarnation? The power of prayer? Astrology? Karma? Yoga as a spiritual practice? The idea that spiritual energy can be rooted in physical objects? Just six percent of us believe in none of these things. With this poll’s margin of error at plus or minus four points and other national polls over the years indicating much the same thing, it’s safe to say that 90 percent of all Americans today believe in something supernatural.

There is so much that is urgent for us to learn from what the social sciences call the dynamics of belief.

more here.

Carlos Eire: The Reformation And The Supernatural

The Lie at the Heart of Overturning Roe Is Now in Plain Sight

Dahlia Lithwick in Slate:

Here is a partial list of the not-medically-trained people who made the medical determination that terminating Kate Cox’s 20-plus-week-old pregnancy would not fall under an approved exception to Texas’ three overlapping abortion bans. Not one of these people, mind you, knows anything about pregnancy, medicine, or Kate Cox’s life, they each just decided that because she did not suffer from “a life-threatening physical condition aggravated by, caused by, or arising from a pregnancy that places the female at risk of death or poses a serious risk of substantial impairment of a major bodily function unless the abortion is performed or induced,” she could not access an abortion, despite the fact that her fetus did receive, from a physician, a diagnosis incompatible with life. The list of people with the moral certainty and medical acumen to restrict this woman’s access to the health care that would in fact preserve her fertility are:

Here is a partial list of the not-medically-trained people who made the medical determination that terminating Kate Cox’s 20-plus-week-old pregnancy would not fall under an approved exception to Texas’ three overlapping abortion bans. Not one of these people, mind you, knows anything about pregnancy, medicine, or Kate Cox’s life, they each just decided that because she did not suffer from “a life-threatening physical condition aggravated by, caused by, or arising from a pregnancy that places the female at risk of death or poses a serious risk of substantial impairment of a major bodily function unless the abortion is performed or induced,” she could not access an abortion, despite the fact that her fetus did receive, from a physician, a diagnosis incompatible with life. The list of people with the moral certainty and medical acumen to restrict this woman’s access to the health care that would in fact preserve her fertility are:

- Ken Paxton, Texas’ nearly impeached attorney general, who appealed a lower court order granting Cox permission to terminate her pregnancy, which she had received following a diagnosis of trisomy 18, a genetic anomaly that virtually always results in miscarriage, stillbirth, or infant death, and frequently causes severe physical pain for the mother and may impair her efforts to bear future children. Add to the list Paxton’s crack team of lawyers who argue—as ace physicians—that Cox should just have had her abortion in Florida if she wants one so badly, then threatened to prosecute her physician and any hospital which aided Cox in Texas despite the existence of a court order specifically shielding them from prosecution.

More here.

‘It’s all gone’: CAR-T therapy forces autoimmune diseases into remission

Heidi Ledford in Nature:

Engineered immun e cells have given 15 people with once-debilitating autoimmune disorders a new lease on life, free from fresh symptoms or treatments. The results raise hopes that the approach — called CAR-T-cell therapy — might one day be extended to a variety of other conditions fuelled by rogue immune cells that produce antibodies against the body’s own tissues. All 15 participants, who each had one of three autoimmune conditions, have remained disease-free or nearly so since their treatment, according to data presented on 9 December at the American Society of Hematology meeting in San Diego, California. The first participants were treated more than two years ago.

e cells have given 15 people with once-debilitating autoimmune disorders a new lease on life, free from fresh symptoms or treatments. The results raise hopes that the approach — called CAR-T-cell therapy — might one day be extended to a variety of other conditions fuelled by rogue immune cells that produce antibodies against the body’s own tissues. All 15 participants, who each had one of three autoimmune conditions, have remained disease-free or nearly so since their treatment, according to data presented on 9 December at the American Society of Hematology meeting in San Diego, California. The first participants were treated more than two years ago.

These successes, although preliminary, have been electric, says Marco Ruella, an oncologist at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. “We’re all excited,” he says. “There’s a lot of potential.”

More here.

Wednesday Poem

Notes on the Art of Poetry

I could never have dreamt that there were such goings-on

in the world between the covers of books,

such sandstorms and ice blasts of words,

such staggering peace, such enormous laughter,

such and so many blinding bright lights,

splashing all over the pages

in a million bits and pieces

all of which were words, words, words,

and each of which were alive forever

in its own delight and glory and oddity and light.

by Dylan Thomas

from Poetic Outlaws

On the Great Poets’ Brawl of ‘68

Nick Ripatrazone at Literary Hub:

One Saturday evening in 1968, the poets battled on Long Island. Drinks spilled into the grass. Punches were flung; some landed. Chilean and French poets stood on a porch and laughed while the Americans brawled. A glass table shattered. Bloody-nosed poets staggered into the coming darkness.

One Saturday evening in 1968, the poets battled on Long Island. Drinks spilled into the grass. Punches were flung; some landed. Chilean and French poets stood on a porch and laughed while the Americans brawled. A glass table shattered. Bloody-nosed poets staggered into the coming darkness.

Allen Ginsberg fell to his knees and prayed.

The World Poetry Conference at Stony Brook University was almost over.

More here.

Democracy and Dr. Kissinger

John M. Owen IV at The Hedgehog Review:

For someone who craved attention, who cultivated reporters and published several memoirs, Henry A. Kissinger liked secrecy. Or better put, he wanted others to keep secrets so that he could reveal them when and how he chose. The lengthy obituary in the New York Times recalls that in 1969, his first year as Richard Nixon’s national security advisor, he was so infuriated by leaks from the White House on the war in Indochina that he had the FBI tap the phones of a number of aides. “If anybody leaks in this administration,” he declared, “I will be the one to leak.”

For someone who craved attention, who cultivated reporters and published several memoirs, Henry A. Kissinger liked secrecy. Or better put, he wanted others to keep secrets so that he could reveal them when and how he chose. The lengthy obituary in the New York Times recalls that in 1969, his first year as Richard Nixon’s national security advisor, he was so infuriated by leaks from the White House on the war in Indochina that he had the FBI tap the phones of a number of aides. “If anybody leaks in this administration,” he declared, “I will be the one to leak.”

The story is revealing. Kissinger the scholar studied power. Kissinger the statesman acquired power, guarded it, and wielded it—in the White House, in the State Department, and around the world. But his death at age 100 leaves us with a puzzle. How is it that this brilliant student of the liberal philosopher Immanuel Kant, this one-time refugee so grateful to America for taking his family in, misunderstood the force of democracy?

More here.

Will an AI smart enough to win math competitions be AGI?

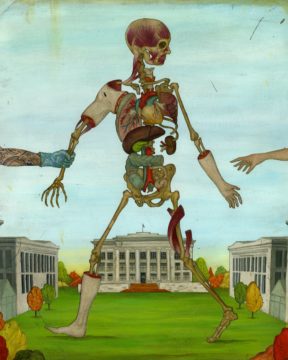

Their Bodies Were Donated to Harvard. Then They Went Missing

Brenna Ehrlich in Rolling Stone:

Once a body is given over to Harvard, that’s meant to be its final destination, where various parts are studied by Ivy League students suited up in surgical gowns and latex gloves. Future doctors and dentists work carefully on their assigned embalmed cadavers, learning about, say, the collection of nerves in the upper arm, or the tiny ligaments and bones that come together at the knee. They’re taught and tested and trained, and the donor’s ashes are usually handed back over to their family, their final sacrifice complete. The donors are generous people like Mazzone, who opted to give up traditional burials in the name of science.

Once a body is given over to Harvard, that’s meant to be its final destination, where various parts are studied by Ivy League students suited up in surgical gowns and latex gloves. Future doctors and dentists work carefully on their assigned embalmed cadavers, learning about, say, the collection of nerves in the upper arm, or the tiny ligaments and bones that come together at the knee. They’re taught and tested and trained, and the donor’s ashes are usually handed back over to their family, their final sacrifice complete. The donors are generous people like Mazzone, who opted to give up traditional burials in the name of science.

When a grieving son or daughter hands over their loved one to Harvard, they’re trusting the storied institution to handle them with respect. They’re passing over their parent or grandparent believing that they’re in safe hands with the academy.

But in 2018, the unthinkable happened. Lodge, the longtime manager of the university’s morgue, and his wife, Denise, a former New Hampshire state government worker, allegedly started selling pieces from those donated bodies.

More here.

Tuesday, December 12, 2023

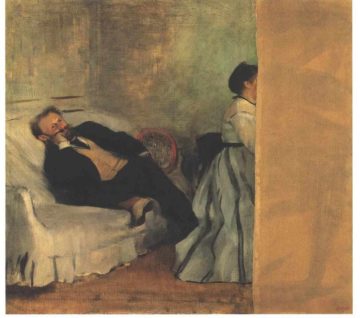

Manet/Degas

Jordan Kantor at Artforum:

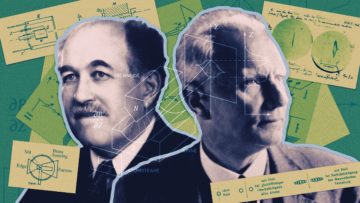

“MANET/DEGAS,” the fall blockbuster at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, begins with an unabashed, double-barreled bang: Édouard Manet’s last great self-portrait, paired up alongside one of Edgar Degas’s first. The juxtaposition provides a thrilling object lesson in the stolid compare-and-contrast curatorial methodology that defines the exhibition, but if it’s meant to show the two artists on an equal footing, it doesn’t stage a fair fight. Forty-six years old when he executed Portrait of the Artist (Manet with a Palette), ca. 1878–79, Manet is at the height of his painterly power, looking backward and forward at once. In an act of supremely confident artistic self-identification, his pose explicitly recalls the Diego Velázquez of Las Meninas, 1656, his lodestar and confessed maître, while his bravado brushwork nods to the advanced painting of the day (Impressionism) and beyond. Degas—two years younger than Manet on the calendar, but a tender twenty in his 1855 Portrait of the Artist—is, on the other hand, just at the beginning of his career. He, too, casts a historical glance, but to local tradition embodied by J.-A.-D. Ingres, and does so more timidly. Charcoal holder in hand as if ready to start (drawing coming before painting in any artist’s education at that time), Degas pictures his aspirations more than his accomplishments. Nevertheless, a piercing gaze already portends the intense psychological depths he would plumb over the next half century. This coupling alone makes a visit to the Met worth the trip.

“MANET/DEGAS,” the fall blockbuster at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, begins with an unabashed, double-barreled bang: Édouard Manet’s last great self-portrait, paired up alongside one of Edgar Degas’s first. The juxtaposition provides a thrilling object lesson in the stolid compare-and-contrast curatorial methodology that defines the exhibition, but if it’s meant to show the two artists on an equal footing, it doesn’t stage a fair fight. Forty-six years old when he executed Portrait of the Artist (Manet with a Palette), ca. 1878–79, Manet is at the height of his painterly power, looking backward and forward at once. In an act of supremely confident artistic self-identification, his pose explicitly recalls the Diego Velázquez of Las Meninas, 1656, his lodestar and confessed maître, while his bravado brushwork nods to the advanced painting of the day (Impressionism) and beyond. Degas—two years younger than Manet on the calendar, but a tender twenty in his 1855 Portrait of the Artist—is, on the other hand, just at the beginning of his career. He, too, casts a historical glance, but to local tradition embodied by J.-A.-D. Ingres, and does so more timidly. Charcoal holder in hand as if ready to start (drawing coming before painting in any artist’s education at that time), Degas pictures his aspirations more than his accomplishments. Nevertheless, a piercing gaze already portends the intense psychological depths he would plumb over the next half century. This coupling alone makes a visit to the Met worth the trip.

more here.