Michel Faber at Literary Hub:

In his memoir Speak, Memory, Vladimir Nabokov reflected: “Music, I regret to say, affects me merely as an arbitrary succession of more or less irritating sounds.”

In his memoir Speak, Memory, Vladimir Nabokov reflected: “Music, I regret to say, affects me merely as an arbitrary succession of more or less irritating sounds.”

The furor over Lolita may have died down, but this confession still has the power to shock. Did the man just say he doesn’t like music? That’s not a matter of preference, such as not caring for sports or pets; it’s a pathological condition.

Accordingly, it’s been given one of those Greek-derived diagnostic labels that allow us to imagine we’ve established a scientific truth rather than merely invented a term: “musical anhedonia.”

And it gets worse: you might have “congenital amusia” (no laughing matter). That’s when, “despite the universality of music,” you find yourself in that “minority of individuals” who, according to The Oxford Handbook of Music and the Brain, “present with very specific musical deficits that cannot be attributed to a general auditory dysfunction, intellectual disability, or a lack of musical exposure.”†

In other words, there are people who don’t get on with music even though they’re not deaf, stupid or ignorant.

More here.

Despite worries about the ethics and safety of AI, the military is betting big on artificial intelligence. The U.S. Department of Defense has requested $1.8 billion for AI and machine learning in 2024, on top of $1.4 billion for a specific initiative that will use AI to link vehicles, sensors, and people scattered across the world. “The U.S. has stated a very active interest in integrating AI across all warfighting functions,” said Benjamin Boudreaux, a policy researcher at the RAND Corporation and co-author of a

Despite worries about the ethics and safety of AI, the military is betting big on artificial intelligence. The U.S. Department of Defense has requested $1.8 billion for AI and machine learning in 2024, on top of $1.4 billion for a specific initiative that will use AI to link vehicles, sensors, and people scattered across the world. “The U.S. has stated a very active interest in integrating AI across all warfighting functions,” said Benjamin Boudreaux, a policy researcher at the RAND Corporation and co-author of a  Americans can’t find enough Adderall. In 2021 pharmacists filled

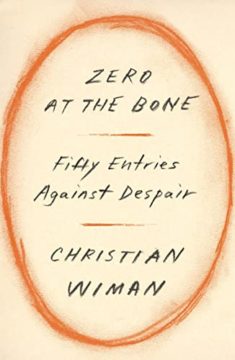

Americans can’t find enough Adderall. In 2021 pharmacists filled  Although Wiman is among the most distinguished Christian writers of his generation, he is uncomfortable with the word “miracle.” But he doesn’t have an alternative description for what happened last Easter or after any of the other treatments that have kept him alive for the past nineteen years. In his new book, “

Although Wiman is among the most distinguished Christian writers of his generation, he is uncomfortable with the word “miracle.” But he doesn’t have an alternative description for what happened last Easter or after any of the other treatments that have kept him alive for the past nineteen years. In his new book, “ The technique known as deep brain stimulation (DBS) has improved cognition in people with traumatic brain injuries, a small clinical trial has found.

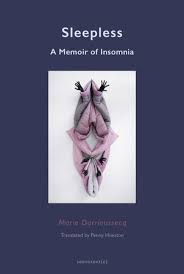

The technique known as deep brain stimulation (DBS) has improved cognition in people with traumatic brain injuries, a small clinical trial has found. I will never forget the first time I saw the devil—leering at me, lurking in the corner of the room, glowing red and approaching my motionless body. I was caught between sleep and waking; I blinked furiously; I struggled to rouse my heavy limbs as he raised his hand to my face. I could not even muster the strength to open my mouth and cry out, help, mommy, help, the monster will get me—

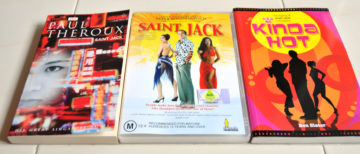

I will never forget the first time I saw the devil—leering at me, lurking in the corner of the room, glowing red and approaching my motionless body. I was caught between sleep and waking; I blinked furiously; I struggled to rouse my heavy limbs as he raised his hand to my face. I could not even muster the strength to open my mouth and cry out, help, mommy, help, the monster will get me— Based on Paul Theroux’s novel of the same name, the film is the director Peter Bogdanovich’s Vietnam movie as well as his Casablanca, a wartime melodrama about a raffish American trying to make a buck on the periphery of the conflict. A lot happens to Jack Flowers—he falls in love, finds a kindred spirit (platonic), fulfills his dream of running a brothel, runs afoul of local gangsters, goes into business with the U.S. military, witnesses the death of a friend, and gets roped in to a smear operation by the CIA—but the film’s tone and pacing belie its density of event. Saint Jack is laid-back, even chill. Applied to heavy material, this attitude usually produces a comedy, but Saint Jack, while full of funny moments, achieves something serious: the sublime.

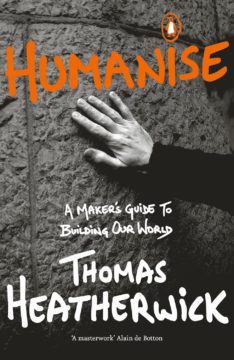

Based on Paul Theroux’s novel of the same name, the film is the director Peter Bogdanovich’s Vietnam movie as well as his Casablanca, a wartime melodrama about a raffish American trying to make a buck on the periphery of the conflict. A lot happens to Jack Flowers—he falls in love, finds a kindred spirit (platonic), fulfills his dream of running a brothel, runs afoul of local gangsters, goes into business with the U.S. military, witnesses the death of a friend, and gets roped in to a smear operation by the CIA—but the film’s tone and pacing belie its density of event. Saint Jack is laid-back, even chill. Applied to heavy material, this attitude usually produces a comedy, but Saint Jack, while full of funny moments, achieves something serious: the sublime. In 1989, when Thomas Heatherwick was eighteen years old, he picked up a Taschen book about the Catalan architect Antoni Gaudí in a student book sale. Inside it, he saw a double-page spread showing Gaudí’s Casa Milà, an apartment building in central Barcelona. ‘I was stunned,’ he writes in the introduction to Humanise. ‘I had no idea that buildings like this existed. I had no idea that such buildings could exist.’

In 1989, when Thomas Heatherwick was eighteen years old, he picked up a Taschen book about the Catalan architect Antoni Gaudí in a student book sale. Inside it, he saw a double-page spread showing Gaudí’s Casa Milà, an apartment building in central Barcelona. ‘I was stunned,’ he writes in the introduction to Humanise. ‘I had no idea that buildings like this existed. I had no idea that such buildings could exist.’ Great critics enjoy magisterial prerogatives, and one of them is the right of comparing John Milton to William Shakespeare. When Samuel Taylor Coleridge took his turn, he was wise enough to refrain from making the two contenders for the title of England’s greatest poet. They are simply too different, he avers. Milton is Shakespeare’s “compeer, not his rival.” Shakespeare, Coleridge explains, “passes into all the forms of human character and passion,” while Milton, “attracts all forms and things to himself, into the unity of his own ideal. All things and modes of action shape themselves anew in the being of Milton; while Shakespeare becomes all things, yet forever remaining himself.” For Coleridge the authorial personality of the one is perfused throughout his work until no stable, freestanding sense of “Shakespeare” remains; the work of the other, line by exacting line, demands to be read in light of the man himself. Not even Dante, who cast himself as the protagonist of his own great poems, or Tolstoy, who pauses a narrative to interject whole philosophical essays, press themselves on the reader as forcefully as does Milton.

Great critics enjoy magisterial prerogatives, and one of them is the right of comparing John Milton to William Shakespeare. When Samuel Taylor Coleridge took his turn, he was wise enough to refrain from making the two contenders for the title of England’s greatest poet. They are simply too different, he avers. Milton is Shakespeare’s “compeer, not his rival.” Shakespeare, Coleridge explains, “passes into all the forms of human character and passion,” while Milton, “attracts all forms and things to himself, into the unity of his own ideal. All things and modes of action shape themselves anew in the being of Milton; while Shakespeare becomes all things, yet forever remaining himself.” For Coleridge the authorial personality of the one is perfused throughout his work until no stable, freestanding sense of “Shakespeare” remains; the work of the other, line by exacting line, demands to be read in light of the man himself. Not even Dante, who cast himself as the protagonist of his own great poems, or Tolstoy, who pauses a narrative to interject whole philosophical essays, press themselves on the reader as forcefully as does Milton. Earlier, during more critical times, he had been accused of many bad things. Now that he’s gone, his critics will get a chance to rehearse the charges. Christopher Hitchens, who made the case that the former secretary of state should be tried as a war criminal, is himself dead. But there’s a long list of witnesses for the prosecution: reporters, historians, and lawyers eager to provide background on any of Kissinger’s actions in Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, East Timor, Bangladesh, against the Kurds, in Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, and Cyprus, among other places.

Earlier, during more critical times, he had been accused of many bad things. Now that he’s gone, his critics will get a chance to rehearse the charges. Christopher Hitchens, who made the case that the former secretary of state should be tried as a war criminal, is himself dead. But there’s a long list of witnesses for the prosecution: reporters, historians, and lawyers eager to provide background on any of Kissinger’s actions in Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, East Timor, Bangladesh, against the Kurds, in Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, and Cyprus, among other places. Today, even seasoned researchers find understanding in short supply when they confront the central open question in theoretical computer science, known as the P versus NP problem. In essence, that question asks whether many computational problems long considered extremely difficult can actually be solved easily (via a secret shortcut we haven’t discovered yet), or whether, as most researchers suspect, they truly are hard. At stake is nothing less than the nature of what’s knowable.

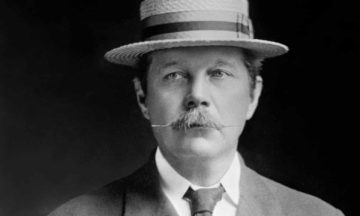

Today, even seasoned researchers find understanding in short supply when they confront the central open question in theoretical computer science, known as the P versus NP problem. In essence, that question asks whether many computational problems long considered extremely difficult can actually be solved easily (via a secret shortcut we haven’t discovered yet), or whether, as most researchers suspect, they truly are hard. At stake is nothing less than the nature of what’s knowable. Arthur Conan Doyle secretly hated his creation Sherlock Holmes and blamed the cerebral detective character for denying him recognition as the author of highbrow historical fiction, according to the historian Lucy Worsley.

Arthur Conan Doyle secretly hated his creation Sherlock Holmes and blamed the cerebral detective character for denying him recognition as the author of highbrow historical fiction, according to the historian Lucy Worsley. By the time Amanda Stern was in her mid-40s, she no longer suffered from clinical depression. And her panic attacks, which had started in childhood, were mostly gone. But instead of feeling happier, she said, “I felt wallpapered in an endless, flat sadness.” Confused, she turned to her therapist, who suggested that she had dysthymia, a mild version of persistent depressive disorder, or P.D.D. Ms. Stern, an author based in New York City, often writes about mental health, but she had never heard the term. She soon realized that she had experienced dysthymia on and off for decades. “I am not suffering from it right now,” she added, “but I imagine I’ll live with it again.” She decided to write about it in her newsletter,

By the time Amanda Stern was in her mid-40s, she no longer suffered from clinical depression. And her panic attacks, which had started in childhood, were mostly gone. But instead of feeling happier, she said, “I felt wallpapered in an endless, flat sadness.” Confused, she turned to her therapist, who suggested that she had dysthymia, a mild version of persistent depressive disorder, or P.D.D. Ms. Stern, an author based in New York City, often writes about mental health, but she had never heard the term. She soon realized that she had experienced dysthymia on and off for decades. “I am not suffering from it right now,” she added, “but I imagine I’ll live with it again.” She decided to write about it in her newsletter,