Andrew Sepielli in Aeon:

Rather than focusing on how people and societies think and talk about morality, normative ethicists try to figure out which things are, simply, morally good or bad, and why. The philosophical sub-field of meta-ethics adopts, naturally, a ‘meta-’ perspective on the kinds of enquiry that normative ethicists engage in. It asks whether there are objectively correct answers to these questions about good or bad, or whether ethics is, rather, a realm of illusion or mere opinion.

Rather than focusing on how people and societies think and talk about morality, normative ethicists try to figure out which things are, simply, morally good or bad, and why. The philosophical sub-field of meta-ethics adopts, naturally, a ‘meta-’ perspective on the kinds of enquiry that normative ethicists engage in. It asks whether there are objectively correct answers to these questions about good or bad, or whether ethics is, rather, a realm of illusion or mere opinion.

Most of my work in the past decade has been in meta-ethics. I believe that there are truths about what’s morally right and wrong. I believe that some of these truths are objective or, as they say in the literature, ‘stance-independent’. That is to say, it’s not my or our disapproval that makes torture morally wrong; torture is wrong because, to put it simply, it hurts people a lot. I believe that these objective moral truths are knowable, and that some people are better than others are at coming to know them. You can even call them ‘moral experts’ if you wish.

More here.

This year marks the tenth anniversary of the International Year of Quinoa (IYQ), a celebratory initiative created by the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. At the inaugural 2013 IYQ, Evo Morales, then president of Bolivia, proclaimed that quinoa was “

This year marks the tenth anniversary of the International Year of Quinoa (IYQ), a celebratory initiative created by the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. At the inaugural 2013 IYQ, Evo Morales, then president of Bolivia, proclaimed that quinoa was “ Born in East Berlin in 1967, Jenny Erpenbeck was 22 when the Wall that had divided her native city for her entire life fell. The socialist German Democratic Republic (GDR), the only country she had known, vanished overnight. By her own account, in the essays collected in Not a Novel: A Memoir in Pieces (2018), this historical rupture confronted her with fundamental questions about continuity and change, agency and contingency, borders and identity, liberation and loss. Although these questions have animated her fiction for more than twenty years, her most recent novel, Kairos (2021), is the first to be centered on how the radically transformative period of German reunification was experienced by those who found themselves, as she writes, “at home on the wrong side.”

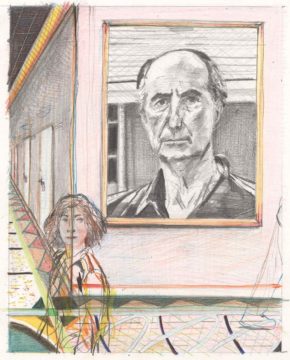

Born in East Berlin in 1967, Jenny Erpenbeck was 22 when the Wall that had divided her native city for her entire life fell. The socialist German Democratic Republic (GDR), the only country she had known, vanished overnight. By her own account, in the essays collected in Not a Novel: A Memoir in Pieces (2018), this historical rupture confronted her with fundamental questions about continuity and change, agency and contingency, borders and identity, liberation and loss. Although these questions have animated her fiction for more than twenty years, her most recent novel, Kairos (2021), is the first to be centered on how the radically transformative period of German reunification was experienced by those who found themselves, as she writes, “at home on the wrong side.” On November 6th, Donald Trump emerged from a New York City courtroom, where he had testified in a civil trial alleging that he and others in the Trump Organization had committed fraud, and gave himself a great review. “I think it went very well,” he told reporters. “If you were there, and you listened, you’d see what a scam this is.” He meant that the case was a scam and not that his company was. “Everybody saw what happened today,” he went on. “And it was very conclusive.”

On November 6th, Donald Trump emerged from a New York City courtroom, where he had testified in a civil trial alleging that he and others in the Trump Organization had committed fraud, and gave himself a great review. “I think it went very well,” he told reporters. “If you were there, and you listened, you’d see what a scam this is.” He meant that the case was a scam and not that his company was. “Everybody saw what happened today,” he went on. “And it was very conclusive.” At first it was just one flower, but Emmanuel Mendoza, an undergraduate student at Texas A&M University, had worked hard to help it bloom. When this five-petaled thing burst forth from his English pea plant collection in late October, and then more flowers and even pea pods followed, he could also see, a little better, the future it might foretell on another world millions of miles from Earth. These weren’t just any pea plants. Some were grown in soil meant to mimic Mars’s inhospitable regolith, the mixture of grainy, eroded rocks and minerals that covers the planet’s surface. To that simulated regolith, Mr. Mendoza had added fertilizer called frass — the waste left after black soldier fly larvae are finished eating and digesting. Essentially, bug manure.

At first it was just one flower, but Emmanuel Mendoza, an undergraduate student at Texas A&M University, had worked hard to help it bloom. When this five-petaled thing burst forth from his English pea plant collection in late October, and then more flowers and even pea pods followed, he could also see, a little better, the future it might foretell on another world millions of miles from Earth. These weren’t just any pea plants. Some were grown in soil meant to mimic Mars’s inhospitable regolith, the mixture of grainy, eroded rocks and minerals that covers the planet’s surface. To that simulated regolith, Mr. Mendoza had added fertilizer called frass — the waste left after black soldier fly larvae are finished eating and digesting. Essentially, bug manure. Mahraganat (which means “festivals” in Arabic) is made primarily by self-taught young men from lower-class backgrounds, whose songs are considered brash, even vulgar, because they rap and sing openly about their lives with seldom a trace of modesty. Egypt’s canonical singers and composers from the 20th century, particularly Umm Kulthum, Abdel Halim Hafez, and Mohammed Abdel Wahab, possessed a virtuosic command of improvisational technique and classical repertoire. By comparison, mahraganat artists appeal first and foremost to friends from the block, weaving a unique lexicon of Arabic slang, boasts, insults, drug references, and sexual innuendo. The artists use Auto-Tune not only to add distortive, festive color to their rugged street anthems, but also for its manufacturer-intended purpose: to keep their voices in tune.

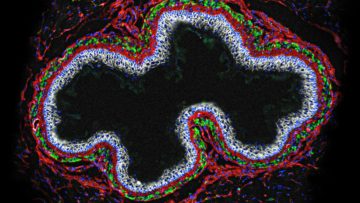

Mahraganat (which means “festivals” in Arabic) is made primarily by self-taught young men from lower-class backgrounds, whose songs are considered brash, even vulgar, because they rap and sing openly about their lives with seldom a trace of modesty. Egypt’s canonical singers and composers from the 20th century, particularly Umm Kulthum, Abdel Halim Hafez, and Mohammed Abdel Wahab, possessed a virtuosic command of improvisational technique and classical repertoire. By comparison, mahraganat artists appeal first and foremost to friends from the block, weaving a unique lexicon of Arabic slang, boasts, insults, drug references, and sexual innuendo. The artists use Auto-Tune not only to add distortive, festive color to their rugged street anthems, but also for its manufacturer-intended purpose: to keep their voices in tune. Breaking down food requires coordination across dozens of cell types and many tissues — from muscle cells and immune cells to blood and lymphatic vessels. Heading this effort is the gut’s very own network of nerve cells, known as the enteric nervous system, which weaves through the intestinal walls from the esophagus down to the rectum. This network can function nearly independently from the brain; indeed, its complexity has earned it the nickname “the second brain.” And just like the brain, it’s made up of two kinds of nervous system cells: neurons and glia.

Breaking down food requires coordination across dozens of cell types and many tissues — from muscle cells and immune cells to blood and lymphatic vessels. Heading this effort is the gut’s very own network of nerve cells, known as the enteric nervous system, which weaves through the intestinal walls from the esophagus down to the rectum. This network can function nearly independently from the brain; indeed, its complexity has earned it the nickname “the second brain.” And just like the brain, it’s made up of two kinds of nervous system cells: neurons and glia.

Twenty-five years ago, the burgeoning science of consciousness studies was rife with promise. With cutting-edge neuroimaging tools leading to new research programmes, the neuroscientist Christof Koch was so optimistic, he bet a case of wine that we’d uncover its secrets by now. The philosopher David Chalmers had serious doubts, because consciousness research is, to put it mildly, difficult. Even what Chalmers called the easy problem of consciousness is hard, and that’s what the bet was about – whether we would uncover the neural structures involved in conscious experience. So, he took

Twenty-five years ago, the burgeoning science of consciousness studies was rife with promise. With cutting-edge neuroimaging tools leading to new research programmes, the neuroscientist Christof Koch was so optimistic, he bet a case of wine that we’d uncover its secrets by now. The philosopher David Chalmers had serious doubts, because consciousness research is, to put it mildly, difficult. Even what Chalmers called the easy problem of consciousness is hard, and that’s what the bet was about – whether we would uncover the neural structures involved in conscious experience. So, he took  The basic issue is that people hear the phrase “quantum mechanics,” or even take a course in it, and come away with the impression that reality is somehow pixelized — made up of smallest possible units — rather than being ultimately smooth and continuous. That’s not right! Quantum theory, as far as it is currently understood, is all about smoothness. The lumpiness of “quanta” is just apparent, although it’s a very important appearance.

The basic issue is that people hear the phrase “quantum mechanics,” or even take a course in it, and come away with the impression that reality is somehow pixelized — made up of smallest possible units — rather than being ultimately smooth and continuous. That’s not right! Quantum theory, as far as it is currently understood, is all about smoothness. The lumpiness of “quanta” is just apparent, although it’s a very important appearance. O

O Things in Gaza have been in constant deterioration. Every single day that passes, new crises are compounded over the crises that already exist. It’s been over 40 days of non-stop bombardment. I’ve been saying many times throughout my coverage that what we have seen in this war, what we are witnessing is unlike any other war in any other place that anyone else has witnessed or lived through. The bombardments of hospitals, of UNRWA schools, residential homes—there’s no place that is not under fire. There’s no place that is not targeted from day one.

Things in Gaza have been in constant deterioration. Every single day that passes, new crises are compounded over the crises that already exist. It’s been over 40 days of non-stop bombardment. I’ve been saying many times throughout my coverage that what we have seen in this war, what we are witnessing is unlike any other war in any other place that anyone else has witnessed or lived through. The bombardments of hospitals, of UNRWA schools, residential homes—there’s no place that is not under fire. There’s no place that is not targeted from day one. It is difficult to predict when one will spend the night at a hotel in Newark, let alone three, and uncommon to agree to such a scenario willingly. If you live there already, you stay home. If you’re there for a professional engagement, your boss made you go. If your flight has been canceled, you go there as a last resort. Whereas, though I felt compelled to be there, I couldn’t point to an authority outside of myself that had forced my hand. The room had been booked a week in advance.

It is difficult to predict when one will spend the night at a hotel in Newark, let alone three, and uncommon to agree to such a scenario willingly. If you live there already, you stay home. If you’re there for a professional engagement, your boss made you go. If your flight has been canceled, you go there as a last resort. Whereas, though I felt compelled to be there, I couldn’t point to an authority outside of myself that had forced my hand. The room had been booked a week in advance.