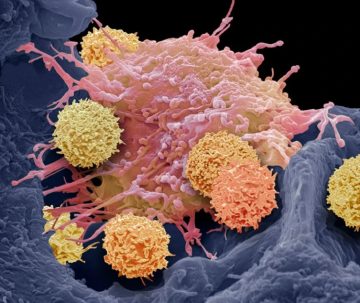

Siddhartha Mukherjee in The New Yorker:

In the nineteen-seventies, Bruce Ames, a biochemist at Berkeley, devised a way to test whether a chemical might cause cancer. Various tenets of cancer biology were already well established. Cancer resulted from genetic mutations—changes in a cell’s DNA sequence that typically cause the cell to divide uncontrollably. These mutations could be inherited, induced by viruses, or generated by random copying errors in dividing cells. They could also be produced by physical or chemical agents: radiation, ultraviolet light, benzene. One day, Ames had found himself reading the list of ingredients on a package of potato chips, and wondering how safe the chemicals used as preservatives really were.

In the nineteen-seventies, Bruce Ames, a biochemist at Berkeley, devised a way to test whether a chemical might cause cancer. Various tenets of cancer biology were already well established. Cancer resulted from genetic mutations—changes in a cell’s DNA sequence that typically cause the cell to divide uncontrollably. These mutations could be inherited, induced by viruses, or generated by random copying errors in dividing cells. They could also be produced by physical or chemical agents: radiation, ultraviolet light, benzene. One day, Ames had found himself reading the list of ingredients on a package of potato chips, and wondering how safe the chemicals used as preservatives really were.

But how to catch a carcinogen? You could expose a rodent to a suspect chemical and see if it developed cancer; toxicologists had done so for generations. But that approach was too slow and costly to deploy on a wide enough scale. Ames—a limber fellow who was partial to wide-lapel tweed jackets and unorthodox neckties—had an idea. If an agent caused DNA mutations in human cells, he reasoned, it was likely to cause mutations in bacterial cells. And Ames had a way of measuring the mutation rate in bacteria, using fast-growing, easy-to-culture strains of salmonella, which he had been studying for a couple of decades. With a few colleagues, he established the assay and published a paper outlining the method with a bold title: “Carcinogens Are Mutagens.” The so-called Ames test for mutagens remains the standard lab technique for screening substances that may cause cancer.

More here.

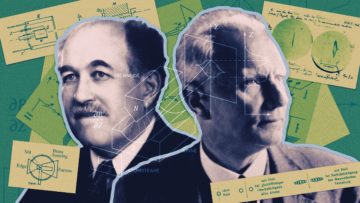

Before Erwin Schrödinger’s cat was simultaneously dead and alive, and before pointlike electrons washed like waves through thin slits, a somewhat lesser-known experiment lifted the veil on the bewildering beauty of the quantum world. In 1922, the German physicists Otto Stern and Walther Gerlach demonstrated that the behavior of atoms was governed by rules that defied expectations — an observation that cemented the still-budding theory of quantum mechanics.

Before Erwin Schrödinger’s cat was simultaneously dead and alive, and before pointlike electrons washed like waves through thin slits, a somewhat lesser-known experiment lifted the veil on the bewildering beauty of the quantum world. In 1922, the German physicists Otto Stern and Walther Gerlach demonstrated that the behavior of atoms was governed by rules that defied expectations — an observation that cemented the still-budding theory of quantum mechanics.

MacGowan died last week at the age of sixty-five, and to many it seemed a small miracle that he lived as long as that. His fame as a drinker was almost as great as his fame as a songwriter and performer, and all that dissipation took a toll. For one thing, it could make him sound mean. In Julien Temple’s 2020 documentary, Crock of Gold: A Few Rounds With Shane MacGowan, we see him insult his wife and friends. He is in a wheelchair, frail, and white as a sheet, making his friend (and the film’s producer) Johnny Depp, only five years younger, seem like the very image of youthful vigor by contrast. “You can be a right bitch,” he tells his wife Victoria. “But you really are very, very nice. And beautiful.”

MacGowan died last week at the age of sixty-five, and to many it seemed a small miracle that he lived as long as that. His fame as a drinker was almost as great as his fame as a songwriter and performer, and all that dissipation took a toll. For one thing, it could make him sound mean. In Julien Temple’s 2020 documentary, Crock of Gold: A Few Rounds With Shane MacGowan, we see him insult his wife and friends. He is in a wheelchair, frail, and white as a sheet, making his friend (and the film’s producer) Johnny Depp, only five years younger, seem like the very image of youthful vigor by contrast. “You can be a right bitch,” he tells his wife Victoria. “But you really are very, very nice. And beautiful.” THIS PAST JULY, the University of Chicago’s National Opinion Research Center (NORC) and the Associated Press published the results of a

THIS PAST JULY, the University of Chicago’s National Opinion Research Center (NORC) and the Associated Press published the results of a  Here is a partial list of the not-medically-trained people who made the medical determination that terminating Kate Cox’s 20-plus-week-old pregnancy would not fall under an approved exception to Texas’

Here is a partial list of the not-medically-trained people who made the medical determination that terminating Kate Cox’s 20-plus-week-old pregnancy would not fall under an approved exception to Texas’  e cells have given 15 people with once-debilitating

e cells have given 15 people with once-debilitating  One Saturday evening in 1968, the poets battled on Long Island. Drinks spilled into the grass. Punches were flung; some landed. Chilean and French poets stood on a porch and laughed while the Americans brawled. A glass table shattered. Bloody-nosed poets staggered into the coming darkness.

One Saturday evening in 1968, the poets battled on Long Island. Drinks spilled into the grass. Punches were flung; some landed. Chilean and French poets stood on a porch and laughed while the Americans brawled. A glass table shattered. Bloody-nosed poets staggered into the coming darkness. For someone who craved attention, who cultivated reporters and published several memoirs, Henry A. Kissinger liked secrecy. Or better put, he wanted others to keep secrets so that he could reveal them when and how he chose. The lengthy obituary in the New York Times recalls that in 1969, his first year as Richard Nixon’s national security advisor, he was so infuriated by leaks from the White House on the war in Indochina that he had the FBI tap the phones of a number of aides. “If anybody leaks in this administration,” he declared, “I will be the one to leak.”

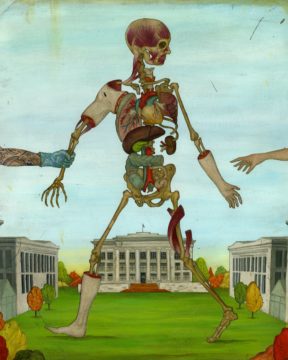

For someone who craved attention, who cultivated reporters and published several memoirs, Henry A. Kissinger liked secrecy. Or better put, he wanted others to keep secrets so that he could reveal them when and how he chose. The lengthy obituary in the New York Times recalls that in 1969, his first year as Richard Nixon’s national security advisor, he was so infuriated by leaks from the White House on the war in Indochina that he had the FBI tap the phones of a number of aides. “If anybody leaks in this administration,” he declared, “I will be the one to leak.” Once a body is given over to Harvard, that’s meant to be its final destination, where various parts are studied by Ivy League students suited up in surgical gowns and latex gloves. Future doctors and dentists work carefully on their assigned embalmed cadavers, learning about, say, the collection of nerves in the upper arm, or the tiny ligaments and bones that come together at the knee. They’re taught and tested and trained, and the donor’s ashes are usually handed back over to their family, their final sacrifice complete. The donors are generous people like Mazzone, who opted to give up traditional burials in the name of science.

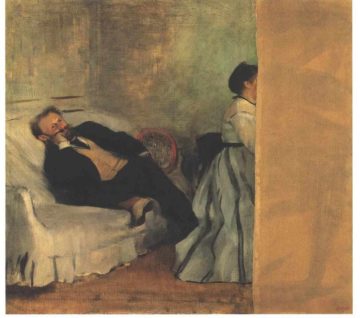

Once a body is given over to Harvard, that’s meant to be its final destination, where various parts are studied by Ivy League students suited up in surgical gowns and latex gloves. Future doctors and dentists work carefully on their assigned embalmed cadavers, learning about, say, the collection of nerves in the upper arm, or the tiny ligaments and bones that come together at the knee. They’re taught and tested and trained, and the donor’s ashes are usually handed back over to their family, their final sacrifice complete. The donors are generous people like Mazzone, who opted to give up traditional burials in the name of science. “MANET/DEGAS,” the fall blockbuster at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, begins with an unabashed, double-barreled bang: Édouard Manet’s last great self-portrait, paired up alongside one of Edgar Degas’s first. The juxtaposition provides a thrilling object lesson in the stolid compare-and-contrast curatorial methodology that defines the exhibition, but if it’s meant to show the two artists on an equal footing, it doesn’t stage a fair fight. Forty-six years old when he executed Portrait of the Artist (Manet with a Palette), ca. 1878–79, Manet is at the height of his painterly power, looking backward and forward at once. In an act of supremely confident artistic self-identification, his pose explicitly recalls the Diego Velázquez of Las Meninas, 1656, his lodestar and confessed maître, while his bravado brushwork nods to the advanced painting of the day (Impressionism) and beyond. Degas—two years younger than Manet on the calendar, but a tender twenty in his 1855 Portrait of the Artist—is, on the other hand, just at the beginning of his career. He, too, casts a historical glance, but to local tradition embodied by J.-A.-D. Ingres, and does so more timidly. Charcoal holder in hand as if ready to start (drawing coming before painting in any artist’s education at that time), Degas pictures his aspirations more than his accomplishments. Nevertheless, a piercing gaze already portends the intense psychological depths he would plumb over the next half century. This coupling alone makes a visit to the Met worth the trip.

“MANET/DEGAS,” the fall blockbuster at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, begins with an unabashed, double-barreled bang: Édouard Manet’s last great self-portrait, paired up alongside one of Edgar Degas’s first. The juxtaposition provides a thrilling object lesson in the stolid compare-and-contrast curatorial methodology that defines the exhibition, but if it’s meant to show the two artists on an equal footing, it doesn’t stage a fair fight. Forty-six years old when he executed Portrait of the Artist (Manet with a Palette), ca. 1878–79, Manet is at the height of his painterly power, looking backward and forward at once. In an act of supremely confident artistic self-identification, his pose explicitly recalls the Diego Velázquez of Las Meninas, 1656, his lodestar and confessed maître, while his bravado brushwork nods to the advanced painting of the day (Impressionism) and beyond. Degas—two years younger than Manet on the calendar, but a tender twenty in his 1855 Portrait of the Artist—is, on the other hand, just at the beginning of his career. He, too, casts a historical glance, but to local tradition embodied by J.-A.-D. Ingres, and does so more timidly. Charcoal holder in hand as if ready to start (drawing coming before painting in any artist’s education at that time), Degas pictures his aspirations more than his accomplishments. Nevertheless, a piercing gaze already portends the intense psychological depths he would plumb over the next half century. This coupling alone makes a visit to the Met worth the trip. Geoffrey Hinton, the computer scientist who is often called “the godfather of A.I.,” handed me a walking stick. “You’ll need one of these,” he said. Then he headed off along a path through the woods to the shore. It wound across a shaded clearing, past a pair of sheds, and then descended by stone steps to a small dock. “It’s slippery here,” Hinton warned, as we started down.

Geoffrey Hinton, the computer scientist who is often called “the godfather of A.I.,” handed me a walking stick. “You’ll need one of these,” he said. Then he headed off along a path through the woods to the shore. It wound across a shaded clearing, past a pair of sheds, and then descended by stone steps to a small dock. “It’s slippery here,” Hinton warned, as we started down. When I first came across Chomsky’s linguistic work, my reactions resembled those of an anthropologist attempting to fathom the beliefs of a previously uncontacted tribe. For anyone in that position, the first rule is to put aside one’s own cultural prejudices and assumptions in order to avoid dismissing every unfamiliar belief. The doctrines encountered may seem unusual, but there are always compelling reasons why those particular doctrines are the ones people adhere to. The task of the anthropologist is to delve into the local context, history, politics and culture of the people under study – in the hope that this may shed light on the logic of those ideas.

When I first came across Chomsky’s linguistic work, my reactions resembled those of an anthropologist attempting to fathom the beliefs of a previously uncontacted tribe. For anyone in that position, the first rule is to put aside one’s own cultural prejudices and assumptions in order to avoid dismissing every unfamiliar belief. The doctrines encountered may seem unusual, but there are always compelling reasons why those particular doctrines are the ones people adhere to. The task of the anthropologist is to delve into the local context, history, politics and culture of the people under study – in the hope that this may shed light on the logic of those ideas. When we think about the food we ate when we were younger, we might be inclined to say that it was tastier and healthier than what we eat today. And while we may be saying this out of a nostalgic tendency, researchers have been looking for a more scientific answer. In several papers, researchers have used food tables – country-by-country compendia of historical information on the mineral composition of foods – to report an apparent decline in micronutrients such as iron, vitamins and zinc in fruit and vegetables over time.

When we think about the food we ate when we were younger, we might be inclined to say that it was tastier and healthier than what we eat today. And while we may be saying this out of a nostalgic tendency, researchers have been looking for a more scientific answer. In several papers, researchers have used food tables – country-by-country compendia of historical information on the mineral composition of foods – to report an apparent decline in micronutrients such as iron, vitamins and zinc in fruit and vegetables over time.