Jorge Cotte in The Nation:

Dune: Part Two, the latest installment of Denis Villaneuve’s adaptation of Frank Herbert’s enduring (and supposedly unadaptable) science fiction series, carries a great weight on its shoulders. It must succeed as a continuation of the first movie without losing new viewers and while bearing the box office’s dreams for an industry that has flagged in comparison to last year. It must give the thrill of a big science fiction blockbuster, while seeming to undermine the transparent teenage fantasies that flourish throughout those stories.

A desert landscape, spices with magical properties, an occupying force, a community of native warriors, and a handsome young hero, bred and trained to liberate them all—Dune: Part Two has all the right elements of success, including a star-studded cast. Timothée Chalamet transforms from waif to despot; Zendaya guides the audience’s perspective with her pensive eyes; Rebecca Ferguson giving us “Reverend Mother”; Javier Bardem is both affable mentor and zealot; and Austin Butler sheds the Elvis accent and all of his hair.

Villeneuve streamlines the vast scope of Herbert’s story into a series of sweeping set pieces, more plentiful in this installment and meticulously executed. The film charts Paul Atreides’s swift rise while characterizing that rise as a cautionary tale too. For just as Paul needs to save his family and his adopted planet, Arrakis, from the occupying Harkonnens, Villeneuve must salvage knowing self-critique from the jaws of teenage fantasy clichés.

More here.

L

L All organisms are made of living cells. While it is difficult to pinpoint exactly when the first cells came to exist, geologists’ best estimates suggest at least as early as

All organisms are made of living cells. While it is difficult to pinpoint exactly when the first cells came to exist, geologists’ best estimates suggest at least as early as

One of the blockbuster films of the

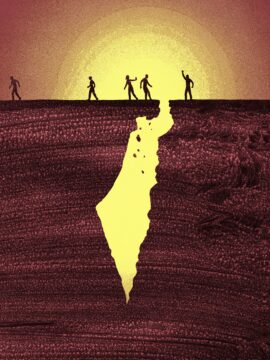

One of the blockbuster films of the  If anti-Zionist Judaism has long sounded like an oxymoron, chalk it up to two factors: the Shoah, which convinced many Jews that they could never again entrust their welfare to a non-Jewish majority; and a remarkably effective effort by the Zionist establishment to weave the nation-state project into the fabric of Jewish life. But things change: A few days after October 7, I was biking along Brooklyn’s Prospect Park when I came upon

If anti-Zionist Judaism has long sounded like an oxymoron, chalk it up to two factors: the Shoah, which convinced many Jews that they could never again entrust their welfare to a non-Jewish majority; and a remarkably effective effort by the Zionist establishment to weave the nation-state project into the fabric of Jewish life. But things change: A few days after October 7, I was biking along Brooklyn’s Prospect Park when I came upon  R

R An egg-laying amphibian found in Brazil nourishes its newly hatched young with a fatty, milk-like substance, according to a study published today in Science

An egg-laying amphibian found in Brazil nourishes its newly hatched young with a fatty, milk-like substance, according to a study published today in Science Sad Cypress is hardly the only murder mystery to revolve around a flower. As writer and landscape historian Marta McDowell observes in her new book,

Sad Cypress is hardly the only murder mystery to revolve around a flower. As writer and landscape historian Marta McDowell observes in her new book,  Cummings takes ‘book’ in its widest sense – clay tablet, paperback, smartphone, codex, scroll. What is defining about the book is not a particular physical form, but rather the idea, as Cummings nicely puts it, ‘of a text with limits, which can be divided into organised contents’. This inclusivity enables Bibliophobia’s signature trait, which is its rapid vaulting across centuries of mark-making. Take the short span between pages 28 and 35. Cummings notes that in the Heroides, Ovid’s rewriting of Homer’s Odyssey, Penelope writes Ulysses a letter, saying don’t write back, just come. This relationship between writing and presence takes us from the web of Penelope to the web of Tim Berners-Lee and Shoshana Zuboff’s theory of the ‘two texts’ of digital media: the search we type in on Google produces a mirror image in the form of a record of the searcher. And then, via Aristotle’s De interpretatione and Voltaire’s Dictionnaire philosophique on writing’s relationship to speech, we’re on to the Greek and Roman alphabets and the relationship between inscriptions in stone and state power, and Freud’s theory of the double (‘an insurance against the extinction of the self’). At moments along the way, Cummings might provide a breathless history of alphabets or Islamic calligraphy.

Cummings takes ‘book’ in its widest sense – clay tablet, paperback, smartphone, codex, scroll. What is defining about the book is not a particular physical form, but rather the idea, as Cummings nicely puts it, ‘of a text with limits, which can be divided into organised contents’. This inclusivity enables Bibliophobia’s signature trait, which is its rapid vaulting across centuries of mark-making. Take the short span between pages 28 and 35. Cummings notes that in the Heroides, Ovid’s rewriting of Homer’s Odyssey, Penelope writes Ulysses a letter, saying don’t write back, just come. This relationship between writing and presence takes us from the web of Penelope to the web of Tim Berners-Lee and Shoshana Zuboff’s theory of the ‘two texts’ of digital media: the search we type in on Google produces a mirror image in the form of a record of the searcher. And then, via Aristotle’s De interpretatione and Voltaire’s Dictionnaire philosophique on writing’s relationship to speech, we’re on to the Greek and Roman alphabets and the relationship between inscriptions in stone and state power, and Freud’s theory of the double (‘an insurance against the extinction of the self’). At moments along the way, Cummings might provide a breathless history of alphabets or Islamic calligraphy. Despite the vast diversity and individuality in every life, we seek patterns, organization, and control. Or, as cognitive psychologist Gregory Murphy puts it: “We put an awful lot of effort into trying to figure out and convince others of just what kind of person someone is, what kind of action something was, and even what kind of object something is.”

Despite the vast diversity and individuality in every life, we seek patterns, organization, and control. Or, as cognitive psychologist Gregory Murphy puts it: “We put an awful lot of effort into trying to figure out and convince others of just what kind of person someone is, what kind of action something was, and even what kind of object something is.” In our galaxy of a hundred billion stars, only three supernovas have been recorded by astronomers: in 1054, in 1572, and in 1604. The Crab Nebula is the remains of the event of 1054, recorded by Chinese astronomers. (When I say the event “of 1054” I mean, of course, the event of which news reached Earth in 1054. The event itself took place six thousand years earlier. The wave-front of light from it hit us in 1054.) Since 1604, the only supernovas that have been seen have been in other galaxies.

In our galaxy of a hundred billion stars, only three supernovas have been recorded by astronomers: in 1054, in 1572, and in 1604. The Crab Nebula is the remains of the event of 1054, recorded by Chinese astronomers. (When I say the event “of 1054” I mean, of course, the event of which news reached Earth in 1054. The event itself took place six thousand years earlier. The wave-front of light from it hit us in 1054.) Since 1604, the only supernovas that have been seen have been in other galaxies. In

In  Six froglets of one of the world’s most threatened frog species have been born at London Zoo.

Six froglets of one of the world’s most threatened frog species have been born at London Zoo. We breathe, eat and

We breathe, eat and