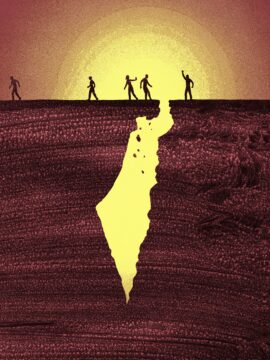

Aaron Gell in The New Republic:

If anti-Zionist Judaism has long sounded like an oxymoron, chalk it up to two factors: the Shoah, which convinced many Jews that they could never again entrust their welfare to a non-Jewish majority; and a remarkably effective effort by the Zionist establishment to weave the nation-state project into the fabric of Jewish life. But things change: A few days after October 7, I was biking along Brooklyn’s Prospect Park when I came upon a demonstration in front of Senator Chuck Schumer’s apartment building. I’d spent the week absorbed in the news, struggling to take in the immensity and cruelty of the Hamas attack and horrified by the ruthlessness of Israel’s military response. As demonstrators, many carrying signs reading NOT IN MY NAME, marched down the road to Grand Army Plaza, I noticed that some were wearing tallitot and yarmulkes, and I found myself overcome with emotion. This, the first post–October 7 protest by Jewish Voice for Peace—a group I had never even heard of—struck me as a welcome response to what we’d been seeing, and a deeply Jewish one. I ditched my bike and joined the throng.

If anti-Zionist Judaism has long sounded like an oxymoron, chalk it up to two factors: the Shoah, which convinced many Jews that they could never again entrust their welfare to a non-Jewish majority; and a remarkably effective effort by the Zionist establishment to weave the nation-state project into the fabric of Jewish life. But things change: A few days after October 7, I was biking along Brooklyn’s Prospect Park when I came upon a demonstration in front of Senator Chuck Schumer’s apartment building. I’d spent the week absorbed in the news, struggling to take in the immensity and cruelty of the Hamas attack and horrified by the ruthlessness of Israel’s military response. As demonstrators, many carrying signs reading NOT IN MY NAME, marched down the road to Grand Army Plaza, I noticed that some were wearing tallitot and yarmulkes, and I found myself overcome with emotion. This, the first post–October 7 protest by Jewish Voice for Peace—a group I had never even heard of—struck me as a welcome response to what we’d been seeing, and a deeply Jewish one. I ditched my bike and joined the throng.

I mention this in the spirit of full disclosure: I’m hardly an objective observer. I’m a secular Jew, with my own particular set of feelings about Israel—a confusing mix of esteem, curiosity, anguish, and sometimes shame.

More here.

R

R An egg-laying amphibian found in Brazil nourishes its newly hatched young with a fatty, milk-like substance, according to a study published today in Science

An egg-laying amphibian found in Brazil nourishes its newly hatched young with a fatty, milk-like substance, according to a study published today in Science Sad Cypress is hardly the only murder mystery to revolve around a flower. As writer and landscape historian Marta McDowell observes in her new book,

Sad Cypress is hardly the only murder mystery to revolve around a flower. As writer and landscape historian Marta McDowell observes in her new book,  Cummings takes ‘book’ in its widest sense – clay tablet, paperback, smartphone, codex, scroll. What is defining about the book is not a particular physical form, but rather the idea, as Cummings nicely puts it, ‘of a text with limits, which can be divided into organised contents’. This inclusivity enables Bibliophobia’s signature trait, which is its rapid vaulting across centuries of mark-making. Take the short span between pages 28 and 35. Cummings notes that in the Heroides, Ovid’s rewriting of Homer’s Odyssey, Penelope writes Ulysses a letter, saying don’t write back, just come. This relationship between writing and presence takes us from the web of Penelope to the web of Tim Berners-Lee and Shoshana Zuboff’s theory of the ‘two texts’ of digital media: the search we type in on Google produces a mirror image in the form of a record of the searcher. And then, via Aristotle’s De interpretatione and Voltaire’s Dictionnaire philosophique on writing’s relationship to speech, we’re on to the Greek and Roman alphabets and the relationship between inscriptions in stone and state power, and Freud’s theory of the double (‘an insurance against the extinction of the self’). At moments along the way, Cummings might provide a breathless history of alphabets or Islamic calligraphy.

Cummings takes ‘book’ in its widest sense – clay tablet, paperback, smartphone, codex, scroll. What is defining about the book is not a particular physical form, but rather the idea, as Cummings nicely puts it, ‘of a text with limits, which can be divided into organised contents’. This inclusivity enables Bibliophobia’s signature trait, which is its rapid vaulting across centuries of mark-making. Take the short span between pages 28 and 35. Cummings notes that in the Heroides, Ovid’s rewriting of Homer’s Odyssey, Penelope writes Ulysses a letter, saying don’t write back, just come. This relationship between writing and presence takes us from the web of Penelope to the web of Tim Berners-Lee and Shoshana Zuboff’s theory of the ‘two texts’ of digital media: the search we type in on Google produces a mirror image in the form of a record of the searcher. And then, via Aristotle’s De interpretatione and Voltaire’s Dictionnaire philosophique on writing’s relationship to speech, we’re on to the Greek and Roman alphabets and the relationship between inscriptions in stone and state power, and Freud’s theory of the double (‘an insurance against the extinction of the self’). At moments along the way, Cummings might provide a breathless history of alphabets or Islamic calligraphy. Despite the vast diversity and individuality in every life, we seek patterns, organization, and control. Or, as cognitive psychologist Gregory Murphy puts it: “We put an awful lot of effort into trying to figure out and convince others of just what kind of person someone is, what kind of action something was, and even what kind of object something is.”

Despite the vast diversity and individuality in every life, we seek patterns, organization, and control. Or, as cognitive psychologist Gregory Murphy puts it: “We put an awful lot of effort into trying to figure out and convince others of just what kind of person someone is, what kind of action something was, and even what kind of object something is.” In our galaxy of a hundred billion stars, only three supernovas have been recorded by astronomers: in 1054, in 1572, and in 1604. The Crab Nebula is the remains of the event of 1054, recorded by Chinese astronomers. (When I say the event “of 1054” I mean, of course, the event of which news reached Earth in 1054. The event itself took place six thousand years earlier. The wave-front of light from it hit us in 1054.) Since 1604, the only supernovas that have been seen have been in other galaxies.

In our galaxy of a hundred billion stars, only three supernovas have been recorded by astronomers: in 1054, in 1572, and in 1604. The Crab Nebula is the remains of the event of 1054, recorded by Chinese astronomers. (When I say the event “of 1054” I mean, of course, the event of which news reached Earth in 1054. The event itself took place six thousand years earlier. The wave-front of light from it hit us in 1054.) Since 1604, the only supernovas that have been seen have been in other galaxies. In

In  Six froglets of one of the world’s most threatened frog species have been born at London Zoo.

Six froglets of one of the world’s most threatened frog species have been born at London Zoo. We breathe, eat and

We breathe, eat and  In the past decade or so, there’s been a flowering of philosophical self-help—books authored by academics but intended to instruct us all. You can learn How to Be a Stoic, How to Be an Epicurean or How William James Can Save Your Life; you can walk Aristotle’s Way and go Hiking with Nietzsche. As of 2020, Oxford University Press has issued a series of “Guides to the Good Life”: short, accessible volumes that draw practical wisdom from historical traditions in philosophy, with entries on existentialism, Buddhism, Epicureanism, Confucianism and Kant.

In the past decade or so, there’s been a flowering of philosophical self-help—books authored by academics but intended to instruct us all. You can learn How to Be a Stoic, How to Be an Epicurean or How William James Can Save Your Life; you can walk Aristotle’s Way and go Hiking with Nietzsche. As of 2020, Oxford University Press has issued a series of “Guides to the Good Life”: short, accessible volumes that draw practical wisdom from historical traditions in philosophy, with entries on existentialism, Buddhism, Epicureanism, Confucianism and Kant. Barbara Comyns (1907–92) was a true original. The word ‘unique’ was often applied to her writing, along with ‘bizarre’, ‘comic’ and ‘macabre’. Her characteristic tone of faux-naïf innocence was established in her first novel, Sisters by a River (1947), which, as the Chicago Tribune observed in 2015, mixed ‘dispassion, levity and veiled ferocity’. Her friend and fellow novelist Ursula Holden put it this way: ‘Barbara Comyns deftly balances savagery with innocence, depravity with Gothic interludes.’ That balance of savagery and innocence is the underlying theme of Avril Horner’s compelling biography of an extraordinary woman.

Barbara Comyns (1907–92) was a true original. The word ‘unique’ was often applied to her writing, along with ‘bizarre’, ‘comic’ and ‘macabre’. Her characteristic tone of faux-naïf innocence was established in her first novel, Sisters by a River (1947), which, as the Chicago Tribune observed in 2015, mixed ‘dispassion, levity and veiled ferocity’. Her friend and fellow novelist Ursula Holden put it this way: ‘Barbara Comyns deftly balances savagery with innocence, depravity with Gothic interludes.’ That balance of savagery and innocence is the underlying theme of Avril Horner’s compelling biography of an extraordinary woman. T

T I

I