Jason Dorrier in Singularity Hub:

AI continues to generate plenty of light and heat. The best models in text and images—now commanding subscriptions and being woven into consumer products—are competing for inches. OpenAI, Google, and Anthropic are all, more or less, neck and neck. It’s no surprise then that AI researchers are looking to push generative models into new territory. As AI requires prodigious amounts of data, one way to forecast where things are going next is to look at what data is widely available online, but still largely untapped. Video, of which there is plenty, is an obvious next step. Indeed, last month, OpenAI previewed a new text-to-video AI called Sora that stunned onlookers. But what about video…games?

AI continues to generate plenty of light and heat. The best models in text and images—now commanding subscriptions and being woven into consumer products—are competing for inches. OpenAI, Google, and Anthropic are all, more or less, neck and neck. It’s no surprise then that AI researchers are looking to push generative models into new territory. As AI requires prodigious amounts of data, one way to forecast where things are going next is to look at what data is widely available online, but still largely untapped. Video, of which there is plenty, is an obvious next step. Indeed, last month, OpenAI previewed a new text-to-video AI called Sora that stunned onlookers. But what about video…games?

It turns out there are quite a few gamer videos online. Google DeepMind says it trained a new AI, Genie, on 30,000 hours of curated video footage showing gamers playing simple platformers—think early Nintendo games—and now it can create examples of its own.

Genie turns a simple image, photo, or sketch into an interactive video game. Given a prompt, say a drawing of a character and its surroundings, the AI can then take input from a player to move the character through its world. In a blog post, DeepMind showed Genie’s creations navigating 2D landscapes, walking around or jumping between platforms. Like a snake eating its tail, some of these worlds were even sourced from AI-generated images. In contrast to traditional video games, Genie generates these interactive worlds frame by frame. Given a prompt and command to move, it predicts the most likely next frames and creates them on the fly. It even learned to include a sense of parallax, a common feature in platformers where the foreground moves faster than the background.

More here.

Lacan collected works by the likes of Duchamp and Picasso, which he displayed proudly in his country home. But to be sure, the most iconic work of his collection, also on view, was Gustave Courbet’s L’Origine du Monde (1866); today, it is owned by the Musée d’Orsay. Famously, Lacan hid this detailed rendering of a vulva behind a sliding wooden door, onto which his friend (and eventual brother-in-law) André Masson painted his own Surrealist rendition. Masson added clouds that drift above an outline of L’Origine’s body, whose curves he recast as hills, her pubic hair resembling a bunch of flowers. L’Origine du Monde almost never leaves d’Orsay. But at the Pompidou-Metz, it no longer hangs alongside other 19th-century works, which often feel prudish in L’Origine’s presence. Instead, the curators have hung it beside more recent representations of vulvas—some of them direct retorts to the famous L’Origine—by the likes of Art & Language, Mircea Cantor, VALIE EXPORT, Victor Man, Betty Tompkins, and Agnès Thurnauer. Deborah de Robertis’s photograph hangs near L’Origine, showing a 2014 performance in which the artist, wearing a gold dress referring to the painting’s gilded frame, squatted in front of the work, spreading her legs wider than Courbet’s model topart her vagina, revealing what she calls “infinity,” or “the origin of the origin,” the depth that Courbet concealed.

Lacan collected works by the likes of Duchamp and Picasso, which he displayed proudly in his country home. But to be sure, the most iconic work of his collection, also on view, was Gustave Courbet’s L’Origine du Monde (1866); today, it is owned by the Musée d’Orsay. Famously, Lacan hid this detailed rendering of a vulva behind a sliding wooden door, onto which his friend (and eventual brother-in-law) André Masson painted his own Surrealist rendition. Masson added clouds that drift above an outline of L’Origine’s body, whose curves he recast as hills, her pubic hair resembling a bunch of flowers. L’Origine du Monde almost never leaves d’Orsay. But at the Pompidou-Metz, it no longer hangs alongside other 19th-century works, which often feel prudish in L’Origine’s presence. Instead, the curators have hung it beside more recent representations of vulvas—some of them direct retorts to the famous L’Origine—by the likes of Art & Language, Mircea Cantor, VALIE EXPORT, Victor Man, Betty Tompkins, and Agnès Thurnauer. Deborah de Robertis’s photograph hangs near L’Origine, showing a 2014 performance in which the artist, wearing a gold dress referring to the painting’s gilded frame, squatted in front of the work, spreading her legs wider than Courbet’s model topart her vagina, revealing what she calls “infinity,” or “the origin of the origin,” the depth that Courbet concealed. In these cases, climate science theory and observations are well aligned. Climate change has increased the frequency of

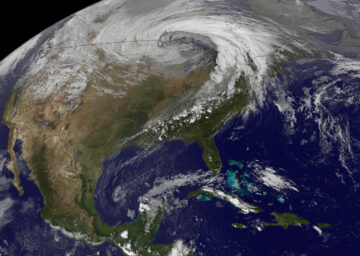

In these cases, climate science theory and observations are well aligned. Climate change has increased the frequency of  What is most jarring is that the story has all the hallmarks of García Márquez; despite its deficiencies, the writing is unmistakably his. At its center is Ana Magdalena Bach, who is a virgin when she marries and remains contentedly faithful to her husband until, at 46, she embarks on a series of explosive one-night stands, a new one each year. She meets the men, all of them strangers, during solo visits to the Caribbean island where her mother is buried. Without fail, every Aug. 16 she lays a bouquet of fresh gladioli on her mother’s grave, clears the weeds that have sprung up around the stone and quickly fills her mother in on the latest family news. Then she gets down to the serious business of finding a partner until morning, when a ferry will take her back to the mainland.

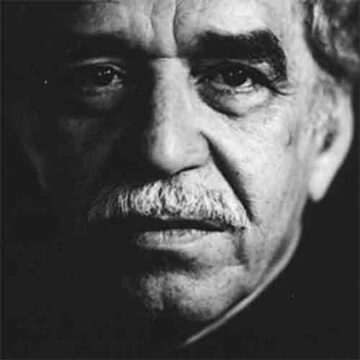

What is most jarring is that the story has all the hallmarks of García Márquez; despite its deficiencies, the writing is unmistakably his. At its center is Ana Magdalena Bach, who is a virgin when she marries and remains contentedly faithful to her husband until, at 46, she embarks on a series of explosive one-night stands, a new one each year. She meets the men, all of them strangers, during solo visits to the Caribbean island where her mother is buried. Without fail, every Aug. 16 she lays a bouquet of fresh gladioli on her mother’s grave, clears the weeds that have sprung up around the stone and quickly fills her mother in on the latest family news. Then she gets down to the serious business of finding a partner until morning, when a ferry will take her back to the mainland. Gabriel García Márquez died ten years ago this April, but people all over the world continue to be stunned, moved, seduced, and transformed by the beauty of his writing and the wildness of his imagination. He is the most translated Spanish-language author of this past century, and in many ways, rightly or wrongly, the made-up Macondo of One Hundred Years of Solitude has come to define the image of Latin America—especially for those of us from the Colombian Caribbean.

Gabriel García Márquez died ten years ago this April, but people all over the world continue to be stunned, moved, seduced, and transformed by the beauty of his writing and the wildness of his imagination. He is the most translated Spanish-language author of this past century, and in many ways, rightly or wrongly, the made-up Macondo of One Hundred Years of Solitude has come to define the image of Latin America—especially for those of us from the Colombian Caribbean. Hollywood rarely shops for film rights at academic presses. Yet if Samuel Moyn’s thought-provoking new book, Liberalism Against Itself, were adapted into a movie, I would recommend making it a courtroom drama.

Hollywood rarely shops for film rights at academic presses. Yet if Samuel Moyn’s thought-provoking new book, Liberalism Against Itself, were adapted into a movie, I would recommend making it a courtroom drama. Understanding elliptic curves is a high-stakes endeavor that has been central to math. So in 2022, when a transatlantic collaboration used statistical techniques and artificial intelligence to discover completely unexpected patterns in elliptic curves, it was a welcome, if unexpected, contribution. “It was just a matter of time before machine learning landed on our front doorstep with something interesting,” said

Understanding elliptic curves is a high-stakes endeavor that has been central to math. So in 2022, when a transatlantic collaboration used statistical techniques and artificial intelligence to discover completely unexpected patterns in elliptic curves, it was a welcome, if unexpected, contribution. “It was just a matter of time before machine learning landed on our front doorstep with something interesting,” said  As environmental, social and humanitarian crises escalate, the world can no longer afford two things: first, the costs of economic inequality; and second, the rich. Between 2020 and 2022, the world’s most affluent 1% of people captured nearly twice as much of the new global wealth created as did the other 99% of individuals put together, and in 2019 they emitted as much carbon dioxide as the poorest two-thirds of humanity. In the decade to 2022, the world’s billionaires more than doubled their wealth, to almost US$12 trillion.

As environmental, social and humanitarian crises escalate, the world can no longer afford two things: first, the costs of economic inequality; and second, the rich. Between 2020 and 2022, the world’s most affluent 1% of people captured nearly twice as much of the new global wealth created as did the other 99% of individuals put together, and in 2019 they emitted as much carbon dioxide as the poorest two-thirds of humanity. In the decade to 2022, the world’s billionaires more than doubled their wealth, to almost US$12 trillion. Sam Crane was in the middle of doing Macbeth when the bullets started flying. A veteran of the British stage, Crane was on the verge of playing the lead in the London production of Harry Potter and the Cursed Child when COVID-19 shut down live performances, and by the U.K.’s third lockdown, he was itching for an audience. So instead of playing to a West End crowd, he found himself orating to a smattering of heavily armed lawbreakers inside the video game Grand Theft Auto. “If I could just request that you refrain from killing each other,” he calls out amid the tomorrows and tomorrows. “And don’t kill the actors either!”

Sam Crane was in the middle of doing Macbeth when the bullets started flying. A veteran of the British stage, Crane was on the verge of playing the lead in the London production of Harry Potter and the Cursed Child when COVID-19 shut down live performances, and by the U.K.’s third lockdown, he was itching for an audience. So instead of playing to a West End crowd, he found himself orating to a smattering of heavily armed lawbreakers inside the video game Grand Theft Auto. “If I could just request that you refrain from killing each other,” he calls out amid the tomorrows and tomorrows. “And don’t kill the actors either!” I

I

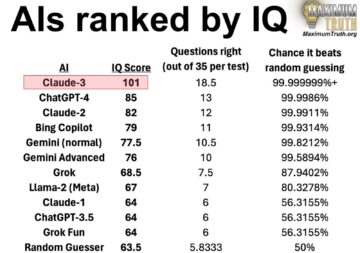

OK so Anthropic’s latest Claude is now more intelligent than the average human being

OK so Anthropic’s latest Claude is now more intelligent than the average human being  We are living through humanity’s fourth industrial revolution, which is largely driven by breakthroughs in digital technologies. Some, like the internet and artificial intelligence, are converging and amplifying each other, with far-reaching consequences for economies and societies. For developing countries, the implications are profound, and questions concerning policy choices and the “appropriateness” of new technologies have become urgent.

We are living through humanity’s fourth industrial revolution, which is largely driven by breakthroughs in digital technologies. Some, like the internet and artificial intelligence, are converging and amplifying each other, with far-reaching consequences for economies and societies. For developing countries, the implications are profound, and questions concerning policy choices and the “appropriateness” of new technologies have become urgent. It’s difficult to imagine Ramadan in Gaza this year. I want to imagine that, even at a time of devastation and deprivation, a personal act of sacrifice can still lend purpose to senselessness. Maybe it can give powerless people a small sense of control. When you fast, you can think, I chose this hunger; it was not forced on me. But maybe that’s wishful thinking. Hunger is painful. It is one of our most primal desires, and the most human; inflicting it on someone else can seem inhuman. The only antidote is to eat. And in the same way that food brings people together I wonder whether its absence keeps us apart. Hunger makes us weak, and not only physically. It cuts us off from the strength that comes from being together.

It’s difficult to imagine Ramadan in Gaza this year. I want to imagine that, even at a time of devastation and deprivation, a personal act of sacrifice can still lend purpose to senselessness. Maybe it can give powerless people a small sense of control. When you fast, you can think, I chose this hunger; it was not forced on me. But maybe that’s wishful thinking. Hunger is painful. It is one of our most primal desires, and the most human; inflicting it on someone else can seem inhuman. The only antidote is to eat. And in the same way that food brings people together I wonder whether its absence keeps us apart. Hunger makes us weak, and not only physically. It cuts us off from the strength that comes from being together.