Heidi Ledford in Nature:

Of the many young people whom Cathy Eng has treated for cancer, the person who stood out the most was a young woman with a 65-year-old’s disease. The 16-year-old had flown from China to Texas to receive treatment for a gastrointestinal cancer that typically occurs in older adults. Her parents had sold their house to fund her care, but it was already too late. “She had such advanced disease, there was not much that I could do,” says Eng, now an oncologist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee. Eng specializes in adult cancers. And although the teenager, who she saw about a decade ago, was Eng’s youngest patient, she was hardly the only one to seem too young and healthy for the kind of cancer that she had.

Of the many young people whom Cathy Eng has treated for cancer, the person who stood out the most was a young woman with a 65-year-old’s disease. The 16-year-old had flown from China to Texas to receive treatment for a gastrointestinal cancer that typically occurs in older adults. Her parents had sold their house to fund her care, but it was already too late. “She had such advanced disease, there was not much that I could do,” says Eng, now an oncologist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee. Eng specializes in adult cancers. And although the teenager, who she saw about a decade ago, was Eng’s youngest patient, she was hardly the only one to seem too young and healthy for the kind of cancer that she had.

Thousands of miles away, in Mumbai, India, surgeon George Barreto had been noticing the same thing. The observations quickly became personal, he says. Friends and family members were also developing improbable forms of cancer. “And then I made a mistake people should never do,” says Barreto, now at Flinders University in Adelaide, Australia. “I promised them I would get to the bottom of this.”

More here.

MIDWAY THROUGH ABOUT ED, Robert Glück revives a line by Frank O’Hara: “Is the earth as full as life was full, of them?” Referring to three of O’Hara’s recently deceased friends, the line appears in “A Step Away from Them,” where it clangs against the rest of the poem and its meandering attention to noontime activity in midtown Manhattan, 1956. It perplexes Glück, whose About Ed remembers Ed Auerlich-Sugai, a lover and friend who died of AIDS-related complications in 1994. “The misdirection threw me,” Glück writes, “from the earth being full, to life being full, instead of Ed being full of life. Was life still full. . . ? Was it always? Was it ever?”

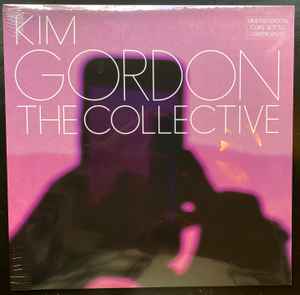

MIDWAY THROUGH ABOUT ED, Robert Glück revives a line by Frank O’Hara: “Is the earth as full as life was full, of them?” Referring to three of O’Hara’s recently deceased friends, the line appears in “A Step Away from Them,” where it clangs against the rest of the poem and its meandering attention to noontime activity in midtown Manhattan, 1956. It perplexes Glück, whose About Ed remembers Ed Auerlich-Sugai, a lover and friend who died of AIDS-related complications in 1994. “The misdirection threw me,” Glück writes, “from the earth being full, to life being full, instead of Ed being full of life. Was life still full. . . ? Was it always? Was it ever?” The day she turned 60, the artist and musician Kim Gordon felt, by her own admission, “shipwrecked.” She had recently gone through a painfully high-profile divorce from her husband of 27 years, Thurston Moore, and in the wake of their

The day she turned 60, the artist and musician Kim Gordon felt, by her own admission, “shipwrecked.” She had recently gone through a painfully high-profile divorce from her husband of 27 years, Thurston Moore, and in the wake of their  The other week there was a lovely opportunity to observe the way in which economists inhabit a mental reality which is quite adjacent to, but often very different from, the economy. An American

The other week there was a lovely opportunity to observe the way in which economists inhabit a mental reality which is quite adjacent to, but often very different from, the economy. An American  In my work as an analyst for the Forecasting Research Institute, and as a member of the forecasting collective Samotsvety, I’ve had plenty of opportunities to see how forecasters err. By and large, these mistakes fall into two categories. The first mistake is in trusting our preconceptions too much. The more we know — and the more confident we are in our knowledge — the easier it is to dismiss information that doesn’t conform to the opinions we already have. But there’s a more insidious second kind of error that bites forecasters — putting too much store in clever models that minimize the role of judgment. Just because there’s math doesn’t make it right.

In my work as an analyst for the Forecasting Research Institute, and as a member of the forecasting collective Samotsvety, I’ve had plenty of opportunities to see how forecasters err. By and large, these mistakes fall into two categories. The first mistake is in trusting our preconceptions too much. The more we know — and the more confident we are in our knowledge — the easier it is to dismiss information that doesn’t conform to the opinions we already have. But there’s a more insidious second kind of error that bites forecasters — putting too much store in clever models that minimize the role of judgment. Just because there’s math doesn’t make it right. The situation in Gaza is rapidly devolving into the worst humanitarian crisis in modern memory, and international health organisations have no long-term plans for addressing the territory’s post-war needs.

The situation in Gaza is rapidly devolving into the worst humanitarian crisis in modern memory, and international health organisations have no long-term plans for addressing the territory’s post-war needs. Larry Summers: Paul Samuelson famously said that if he would be allowed to write the economics textbooks, he didn’t care who would get to perform as the finance ministers going forward. So I think what happens in universities is immensely important. And I think there is a widespread sense—and it is, I think, unfortunately, with considerable validity—that many of our leading universities have lost their way; that values that one associated as central to universities—excellence, truth, integrity, opportunity—have come to seem like secondary values relative to the pursuit of certain concepts of social justice, the veneration of certain concepts of identity, the primacy of feeling over analysis, and the elevation of subjective perspective. And that has led to clashes within universities and, more importantly, an enormous estrangement between universities and the broader society.

Larry Summers: Paul Samuelson famously said that if he would be allowed to write the economics textbooks, he didn’t care who would get to perform as the finance ministers going forward. So I think what happens in universities is immensely important. And I think there is a widespread sense—and it is, I think, unfortunately, with considerable validity—that many of our leading universities have lost their way; that values that one associated as central to universities—excellence, truth, integrity, opportunity—have come to seem like secondary values relative to the pursuit of certain concepts of social justice, the veneration of certain concepts of identity, the primacy of feeling over analysis, and the elevation of subjective perspective. And that has led to clashes within universities and, more importantly, an enormous estrangement between universities and the broader society. In 1889, a French doctor named Francois-Gilbert Viault climbed down from a mountain in the Andes, drew blood from his arm and inspected it under a microscope. Dr. Viault’s red blood cells, which ferry oxygen, had surged 42 percent. He had discovered a mysterious power of the human body: When it needs more of these crucial cells, it can make them on demand. In the early 1900s, scientists theorized that a hormone was the cause. They called the theoretical hormone erythropoietin, or “red maker” in Greek. Seven decades later, researchers found actual erythropoietin after filtering

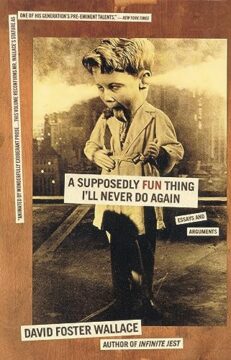

In 1889, a French doctor named Francois-Gilbert Viault climbed down from a mountain in the Andes, drew blood from his arm and inspected it under a microscope. Dr. Viault’s red blood cells, which ferry oxygen, had surged 42 percent. He had discovered a mysterious power of the human body: When it needs more of these crucial cells, it can make them on demand. In the early 1900s, scientists theorized that a hormone was the cause. They called the theoretical hormone erythropoietin, or “red maker” in Greek. Seven decades later, researchers found actual erythropoietin after filtering  I might’ve stayed away from David Foster Wallace forever were it not for Coco Gauff, whose U.S. Open win last year stirred within me some need to try to fall back in love with tennis—not as a player, but as a literary spectator. Steering clear of the courts, I stuck close to the page, reading what I could of the sport (John McPhee’s

I might’ve stayed away from David Foster Wallace forever were it not for Coco Gauff, whose U.S. Open win last year stirred within me some need to try to fall back in love with tennis—not as a player, but as a literary spectator. Steering clear of the courts, I stuck close to the page, reading what I could of the sport (John McPhee’s

The main thing that I learned in journalism school was that I didn’t belong in journalism school. The other thing I learned was that journalists were deeply anti-intellectual. They were suspicious of ideas; they regarded theories as pretentious; they recoiled at big words (or had never heard of them). For a long time, I had contempt for the profession on that score. In recent years, though, this has yielded to a measure of respect. For notice that I didn’t say that journalists are anti-intellectual. I said they were. Now they’re something else: pseudo-intellectual. And that is much worse.

The main thing that I learned in journalism school was that I didn’t belong in journalism school. The other thing I learned was that journalists were deeply anti-intellectual. They were suspicious of ideas; they regarded theories as pretentious; they recoiled at big words (or had never heard of them). For a long time, I had contempt for the profession on that score. In recent years, though, this has yielded to a measure of respect. For notice that I didn’t say that journalists are anti-intellectual. I said they were. Now they’re something else: pseudo-intellectual. And that is much worse. Set out in search of the history of women’s relationship with sex and you will—with a bit of luck—find a very amusing engraving from the seventeenth century lurking in the shallows of the internet. It shows three young women standing at a sales counter.

Set out in search of the history of women’s relationship with sex and you will—with a bit of luck—find a very amusing engraving from the seventeenth century lurking in the shallows of the internet. It shows three young women standing at a sales counter. It’s that time of year again. On March 10, stars will gather in Hollywood’s Dolby Theatre to celebrate the best and brightest in filmmaking at the

It’s that time of year again. On March 10, stars will gather in Hollywood’s Dolby Theatre to celebrate the best and brightest in filmmaking at the