Michael Schulson in Undark:

IT’S A FAMILIAR pandemic story: In September 2020, Angela McLean and John Edmunds found themselves sitting in the same Zoom meeting, listening to a discussion they didn’t like. At some point during the meeting, McLean — professor of mathematical biology at the Oxford University, dame commander of the Order of the British Empire, fellow of the Royal Society of London, and then-chief scientific adviser to the United Kingdom’s Ministry of Defense — sent Edmunds a message on WhatsApp.

IT’S A FAMILIAR pandemic story: In September 2020, Angela McLean and John Edmunds found themselves sitting in the same Zoom meeting, listening to a discussion they didn’t like. At some point during the meeting, McLean — professor of mathematical biology at the Oxford University, dame commander of the Order of the British Empire, fellow of the Royal Society of London, and then-chief scientific adviser to the United Kingdom’s Ministry of Defense — sent Edmunds a message on WhatsApp.

“Who is this fuckwitt?” she asked.

The message was evidently referring to Carl Heneghan, director of the Center for Evidence-Based Medicine at Oxford. He was on Zoom that day, along with McLean and Edmunds and two other experts, to advise the British prime minister on the Covid-19 pandemic. Their disagreement — recently made public as part of a British government inquiry into the Covid-19 response — is one small chapter in a long-running clash between two schools of thought within the world of health care. McLean and Edmunds are experts in infectious disease modeling; they build elaborate simulations of pandemics, which they use to predict how infections will spread and how best to slow them down. Often, during the Covid-19 pandemic, such models were used alongside other forms of evidence to urge more restrictions to slow the spread of the disease. Heneghan, meanwhile, is a prominent figure in the world of evidence-based medicine, or EBM. The movement aims to help doctors draw on the best available evidence when making decisions and advising patients. Over the past 30 years, EBM has transformed the practice of medicine worldwide.

More here.

When I was editing my debut novel,

When I was editing my debut novel,  “Indelible in the hippocampus is the laughter.”

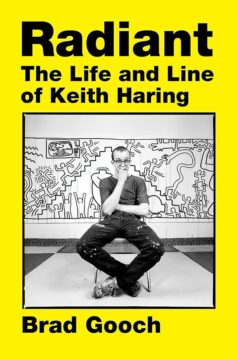

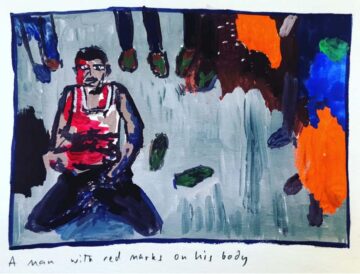

“Indelible in the hippocampus is the laughter.” While modern audiences might be more likely to understand the import of these themes, many critics at the time discounted Haring’s work as “fast food,” as one put it, adding, “It’s a good time, it’s boogieing on a Saturday night, it’s alive, but great, no.” One curator blamed Haring’s commercial appeal for the reluctance to take his art seriously, saying, “I think Haring was so successful that other artists could not forgive him.” Gallerist Jeffrey Deitch pointed out that most artists enjoying Haring’s level of financial success would have been churning out even more sellable work. But Haring was committed to public projects such as murals, which he did for little or no compensation.

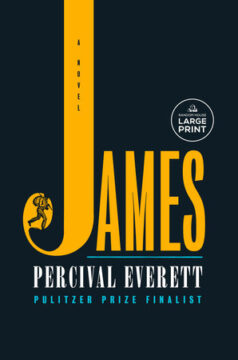

While modern audiences might be more likely to understand the import of these themes, many critics at the time discounted Haring’s work as “fast food,” as one put it, adding, “It’s a good time, it’s boogieing on a Saturday night, it’s alive, but great, no.” One curator blamed Haring’s commercial appeal for the reluctance to take his art seriously, saying, “I think Haring was so successful that other artists could not forgive him.” Gallerist Jeffrey Deitch pointed out that most artists enjoying Haring’s level of financial success would have been churning out even more sellable work. But Haring was committed to public projects such as murals, which he did for little or no compensation. Everett mostly sticks to the broad outlines of Twain’s novel. He is riding the same currents; the book flows inexorably, like a river, yet its short chapters keep the movement swift. James is on the run, of course, because he has learned that Miss Watson plans to sell him to a man in New Orleans. He will be separated from his wife and children. Huck is on the run because he has faked his own death after being beaten by his father. They find each other on an island in the Mississippi, and their flight begins. The reader slowly discovers that their bonds run deeper than friendship.

Everett mostly sticks to the broad outlines of Twain’s novel. He is riding the same currents; the book flows inexorably, like a river, yet its short chapters keep the movement swift. James is on the run, of course, because he has learned that Miss Watson plans to sell him to a man in New Orleans. He will be separated from his wife and children. Huck is on the run because he has faked his own death after being beaten by his father. They find each other on an island in the Mississippi, and their flight begins. The reader slowly discovers that their bonds run deeper than friendship. I was sitting on a train, travelling from my home in Poughkeepsie to New York City, when I saw a note on my phone asking me to write the piece below. I began thinking of a painting, a portrait of his father painted by the Indian artist Atul Dodiya, but the other memory that came to me was that I had long ago been sitting in the same Metro North train bound for New York City when the idea for my new novel,

I was sitting on a train, travelling from my home in Poughkeepsie to New York City, when I saw a note on my phone asking me to write the piece below. I began thinking of a painting, a portrait of his father painted by the Indian artist Atul Dodiya, but the other memory that came to me was that I had long ago been sitting in the same Metro North train bound for New York City when the idea for my new novel,  While Sutter loves science, he believes there are deep problems with the way science is actually done. He began to notice some of those problems before the Covid-19 pandemic, but it was Covid that brought many of them to the fore. “I was watching, in real time, the erosion of trust in science as an institution,” he said, “and the difficulty scientists had in communicating with the public about a very urgent, very important matter that we were learning about as we were speaking about it.”

While Sutter loves science, he believes there are deep problems with the way science is actually done. He began to notice some of those problems before the Covid-19 pandemic, but it was Covid that brought many of them to the fore. “I was watching, in real time, the erosion of trust in science as an institution,” he said, “and the difficulty scientists had in communicating with the public about a very urgent, very important matter that we were learning about as we were speaking about it.” Friedrich Nietzsche once wrote: ‘Mankind likes to put questions of origins and beginnings out of its mind.’ With apologies to Nietzsche, the ‘questions of origins and beginnings’ are in fact more controversial and hotly debated. The ongoing Israel-Gaza war has reopened old debates over the circumstances of Israel’s founding and the origins of the Palestinian refugee crisis. Meanwhile, in a speech he gave on the eve of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Vladimir Putin insisted that ‘since time immemorial’ Russia had always included Ukraine, a situation that was disrupted by the establishment of the Soviet Union. And in the US, The New York Times’

Friedrich Nietzsche once wrote: ‘Mankind likes to put questions of origins and beginnings out of its mind.’ With apologies to Nietzsche, the ‘questions of origins and beginnings’ are in fact more controversial and hotly debated. The ongoing Israel-Gaza war has reopened old debates over the circumstances of Israel’s founding and the origins of the Palestinian refugee crisis. Meanwhile, in a speech he gave on the eve of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Vladimir Putin insisted that ‘since time immemorial’ Russia had always included Ukraine, a situation that was disrupted by the establishment of the Soviet Union. And in the US, The New York Times’  Last summer, as I sat waiting for a train in Penn Station, I noticed a figure approaching and trying to get my attention. Keenly aware that I was patronizing an ostensibly public space where the only seats were placed behind gates monitored by security guards, I was eager to part with a few dollars if asked. It took me a moment to register that the woman standing before me, wearing a blue habit and a crucifix around her neck, was asking to borrow my cell phone. She needed to call her elderly father, she said, to tell him that her train would be late, and that she would seek shelter for the night at a convent she had heard of in Boston before continuing her journey. Flooded with a sense of the auspicious, I asked her what her destination was. She said she was heading—as I somehow had felt she would be—to her father’s house on Cape Cod. She named the same town where my in-laws live, to which I, too, was traveling. My husband Jack was picking me up in Providence to drive there, I told her. Would she like a ride?

Last summer, as I sat waiting for a train in Penn Station, I noticed a figure approaching and trying to get my attention. Keenly aware that I was patronizing an ostensibly public space where the only seats were placed behind gates monitored by security guards, I was eager to part with a few dollars if asked. It took me a moment to register that the woman standing before me, wearing a blue habit and a crucifix around her neck, was asking to borrow my cell phone. She needed to call her elderly father, she said, to tell him that her train would be late, and that she would seek shelter for the night at a convent she had heard of in Boston before continuing her journey. Flooded with a sense of the auspicious, I asked her what her destination was. She said she was heading—as I somehow had felt she would be—to her father’s house on Cape Cod. She named the same town where my in-laws live, to which I, too, was traveling. My husband Jack was picking me up in Providence to drive there, I told her. Would she like a ride?