Holly Case in the Boston Review:

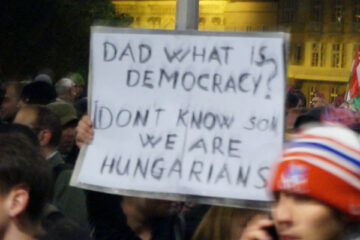

Last September an article on the front page of a leading Hungarian daily began, “The story of the ever-deepening refugee crisis is taking ever more unexpected turns.” A prominent Hungarian intellectual and former dissident, György Konrád, had come out in support of the efforts of the Hungarian government to build a wall to keep out newcomers and to cast them as economic opportunists rather than political refugees. In another corner of the Hungarian media, pundits were citing passages from The Final Tavern (A végső kocsma), a 2014 book by Holocaust survivor and 2002 Nobel laureate Imre Kertész, who passed away last month. In the book, Kertész was sharply critical of liberals’ welcoming attitude toward Muslim refugees and migrants. His and Konrád’s statements were registered with incredulity in the liberal press and with undisguised relish on the right.

Last September an article on the front page of a leading Hungarian daily began, “The story of the ever-deepening refugee crisis is taking ever more unexpected turns.” A prominent Hungarian intellectual and former dissident, György Konrád, had come out in support of the efforts of the Hungarian government to build a wall to keep out newcomers and to cast them as economic opportunists rather than political refugees. In another corner of the Hungarian media, pundits were citing passages from The Final Tavern (A végső kocsma), a 2014 book by Holocaust survivor and 2002 Nobel laureate Imre Kertész, who passed away last month. In the book, Kertész was sharply critical of liberals’ welcoming attitude toward Muslim refugees and migrants. His and Konrád’s statements were registered with incredulity in the liberal press and with undisguised relish on the right.

Anyone who has followed the serpentine trajectory of Hungarian politics since the controlled collapse of state socialism in 1989 might be forgiven for throwing their hands up in confusion. For more than two and a half decades, Hungarian political life has been a story of reversals.

More here.

Back in December 2016, I was sitting in my office at the World Bank in Washington, D.C., feeling unmoored and disheartened. Every day, I walked through Lafayette Park in front of the White House to get to my work. But lately, the noise had been so loud and ugly about the Muslim ban and building a wall. I was beginning to panic. What’s a person like me even supposed to do about this? Why am I even here?

Back in December 2016, I was sitting in my office at the World Bank in Washington, D.C., feeling unmoored and disheartened. Every day, I walked through Lafayette Park in front of the White House to get to my work. But lately, the noise had been so loud and ugly about the Muslim ban and building a wall. I was beginning to panic. What’s a person like me even supposed to do about this? Why am I even here? In one way or another, the superrich have always been trying to extend their lives. Ancient Egyptians crammed their tombs with everything they’d need to live on in an afterlife not unlike their own world, just filled with more fun. In the modern era, the ultra-wealthy have attempted to live on through their legacies: sponsoring museums and galleries to immortalize their names.

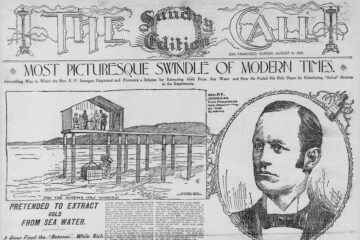

In one way or another, the superrich have always been trying to extend their lives. Ancient Egyptians crammed their tombs with everything they’d need to live on in an afterlife not unlike their own world, just filled with more fun. In the modern era, the ultra-wealthy have attempted to live on through their legacies: sponsoring museums and galleries to immortalize their names. CRAP paper accepted by journal

CRAP paper accepted by journal Bright, impetuous and obsessed with beautiful things, Isabella Stewart Gardner led a life out of a Gilded Age novel. Born into a wealthy New York family, she married into an even wealthier Boston one when she wed John Lowell Gardner in 1860, only to be ostracized by her adopted city’s more conservative denizens, who found her self-assurance and penchant for “jollification” a bit much.

Bright, impetuous and obsessed with beautiful things, Isabella Stewart Gardner led a life out of a Gilded Age novel. Born into a wealthy New York family, she married into an even wealthier Boston one when she wed John Lowell Gardner in 1860, only to be ostracized by her adopted city’s more conservative denizens, who found her self-assurance and penchant for “jollification” a bit much. The world can be impatient with slow writers. Nearly a decade after Jeffrey Eugenides published

The world can be impatient with slow writers. Nearly a decade after Jeffrey Eugenides published  Kevin Hart insists he’s never written a joke.

Kevin Hart insists he’s never written a joke. M

M You might think you remember taking a trip to Disneyland when you were 18 months old, or that time you had chickenpox when you were 2—but you almost certainly don’t. However real they may seem, your earliest treasured memories were probably implanted by seeing photos or hearing your parents’ stories about waiting in line for the spinning teacups. Recalling those manufactured memories again and again consolidated them in your brain, making them as vivid as your last summer vacation.

You might think you remember taking a trip to Disneyland when you were 18 months old, or that time you had chickenpox when you were 2—but you almost certainly don’t. However real they may seem, your earliest treasured memories were probably implanted by seeing photos or hearing your parents’ stories about waiting in line for the spinning teacups. Recalling those manufactured memories again and again consolidated them in your brain, making them as vivid as your last summer vacation.