Gardiner Means in Phenomenal World:

Gardiner Means in Phenomenal World:

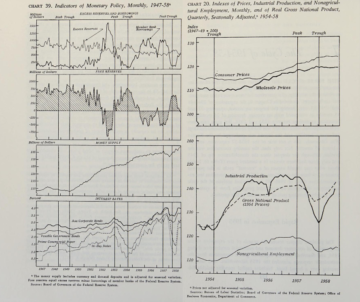

If they are remembered at all, the 1950s are now thought of as a lost golden age of stable growth and political economic consensus. But the second half of the decade saw rising prices, tightening financial conditions, diminished industrial employment, and stagnant investment. With knowledge of the turbulence that followed, historians have increasingly interpreted the economic history of the late 1950s not as a minor aberration to a stable political order but as revealing structural pathologies latent in the twentieth-century industrial economy. If contemporaries did not yet use the word “stagflation,” they might as well have, referring to the decade’s rising prices with terms such as “new inflation” and “recession-cum-inflation.”

Gardiner C. Means was one of the most astute analysts of the policy dilemma created by this anti-inflationary monetary policy. Means owed his original prominence to The Modern Corporation and Private Property, which he co-authored with Adolf Berle in 1932. This surprise best-seller popularized the idea that corporate capitalism—specifically, its tendency to separate ownership and management—represented a radical transformation in social organization. The book placed the question of corporate power on the agenda at the depths of the Great Depression, and Means parlayed this commercial and intellectual success into a position at the Department of Agriculture in the first Franklin Roosevelt administration. The New Deal’s response to that conjuncture was in part shaped by his distinctive analysis: the length and depth of the 1930s recession was, he argued, a consequence of an imbalance in relative prices between economic sectors—a diagnosis which prescribed national economic planning to raise agricultural prices and allow farmers to afford an expanded volume of industrial production.

Twenty-five years later, Means brought his familiarity with corporate pricing patterns to the distinctive problem of the postwar economy.

More here.