Kate Mackenzie and Tim Sahay in Polycrisis:

We live in a dysfunctional system in which money flows out of the countries that need it most and into the coffers of the wealthiest. In 2023, the private sector collected $68 billion more in interest and principal repayments than it lent to the developing world. International financial institutions and assistance agencies extracted another $40 billion, while net concessional assistance from international financial institutions was only $2 billion—even as famine spread. The result is that as developing economies make exorbitant interest payments to their creditors, they are forced to cut spending on health, education, and infrastructure at home. Half of the world’s poorest countries are now poorer than they were before the pandemic.

At The Polycrisis we have been tracking the whipsaw of the global financial system amid private finance mantras, interest-rate hikes at the Fed, and the explosion of debt in the global South. In our dispatches on IMF meetings, the Paris conference on debt and climate, the BRICS summit, Barbados, Brussels, Ukraine, and Pakistan, we have sought to throw light on the political economy of financial distress. Who is in need? What do they get from whom, and under what conditions?

The polycentric financial “order”

The World Bank boosted its lending in the wake of the Covid pandemic, but is still well short of meeting the financing needs of developing countries. At the Spring meetings of the IMF and World Bank this week, the question of who adds capital for development, climate resilience, and the energy transition is high on the agenda.

Long-term finance is one thing, but in a crisis, it’s liquidity that counts most—and it can be key to warding off the kind of panic that drives investment away.

In all this, the dollar remains king. Want to make payments? Send an invoice? Store your wealth? Borrow across borders? Chatter about any replacement of the dollar as the dominant reserve currency is overblown. No other contender is willing to run the current-account deficit necessary to be a global reserve issuer. And when a storm arrives, liquidity flows to those with “safe assets” closest to the imperial core, while the burden of “structural adjustment” falls on the poorest and weakest shoulders in each society.

More here.

The chorus of the theme song for the movie Fame, performed by the late actress Irene Cara, includes the line “I’m gonna live forever.” Cara was, of course, singing about the posthumous longevity that fame can confer. But a literal expression of this hubris resonates in some corners of the world—especially in the technology industry. In Silicon Valley, immortality is sometimes elevated to the status of a corporeal goal. Plenty of big names in big tech have sunk funding into ventures aiming to solve the problem of death as if it were just an upgrade to your smartphone’s operating system.

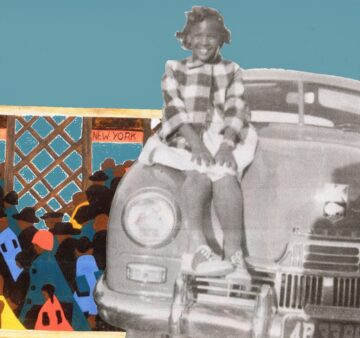

The chorus of the theme song for the movie Fame, performed by the late actress Irene Cara, includes the line “I’m gonna live forever.” Cara was, of course, singing about the posthumous longevity that fame can confer. But a literal expression of this hubris resonates in some corners of the world—especially in the technology industry. In Silicon Valley, immortality is sometimes elevated to the status of a corporeal goal. Plenty of big names in big tech have sunk funding into ventures aiming to solve the problem of death as if it were just an upgrade to your smartphone’s operating system. As the historian Nell Irvin Painter has learned over the course of her eight decades on this earth, inspiration can come from some unlikely places.

As the historian Nell Irvin Painter has learned over the course of her eight decades on this earth, inspiration can come from some unlikely places. Since the 19th century, large numbers of villagers in the poorer parts of Italy have migrated to more prosperous regions and countries. The migration continues; in some places, populations have shrunk so dramatically that there are no longer enough patients to keep the local doctor in business, or enough children to fill the school. Young people who moved away to study or work didn’t want to return, and when their parents died, the family homes stood empty, sometimes for decades. Around 2010, the village of Salemi in western Sicily was one of the first towns to come up with an idea: What if you could fill them again by offering the properties for sale at a ridiculously low price?

Since the 19th century, large numbers of villagers in the poorer parts of Italy have migrated to more prosperous regions and countries. The migration continues; in some places, populations have shrunk so dramatically that there are no longer enough patients to keep the local doctor in business, or enough children to fill the school. Young people who moved away to study or work didn’t want to return, and when their parents died, the family homes stood empty, sometimes for decades. Around 2010, the village of Salemi in western Sicily was one of the first towns to come up with an idea: What if you could fill them again by offering the properties for sale at a ridiculously low price? Vaccination led to the global eradication of smallpox in 1980. Even today, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation lists one of the goals of its malaria program as “ending malaria for good.” In recent years, Tufts University launched its

Vaccination led to the global eradication of smallpox in 1980. Even today, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation lists one of the goals of its malaria program as “ending malaria for good.” In recent years, Tufts University launched its YOU KNOW KEITH HARING. He drew breakdancers and mushroom clouds and triclops and dicks and death and he drew Warhol’s envy. He painted on the Berlin Wall and on Bill T. Jones and on Grace Jones. He painted CRACK IS WACK and SILENCE = DEATH. He smuggled SAMO into SVA to tag the school’s graffiti-blitzed stairwell. His chalk ikons perfused Ed Koch’s decrepit metro, scrawled on seemingly every empty ad space. They called him Chalkman and the Degas of the B-boys, they called him genius and sellout. Club 57, Danceteria, Area, the Roxy, the Pyramid, the Palladium, the Mudd Club, Paradise Garage. Uniqlo, Coach, Nike.

YOU KNOW KEITH HARING. He drew breakdancers and mushroom clouds and triclops and dicks and death and he drew Warhol’s envy. He painted on the Berlin Wall and on Bill T. Jones and on Grace Jones. He painted CRACK IS WACK and SILENCE = DEATH. He smuggled SAMO into SVA to tag the school’s graffiti-blitzed stairwell. His chalk ikons perfused Ed Koch’s decrepit metro, scrawled on seemingly every empty ad space. They called him Chalkman and the Degas of the B-boys, they called him genius and sellout. Club 57, Danceteria, Area, the Roxy, the Pyramid, the Palladium, the Mudd Club, Paradise Garage. Uniqlo, Coach, Nike. Indians tend to fetishize elections, which now wholly define their self-imagination as a democratic society, obscuring other institutional necessities. The

Indians tend to fetishize elections, which now wholly define their self-imagination as a democratic society, obscuring other institutional necessities. The  Lithuania has lost the Eurovision Song Contest thirty times. The first loss, in 1994, was awarded to Ovidijus Vysniauskas’ « Lopšinė mylimai » (Lullaby for my lover). The ballad about a secret love, worthy of a soundtrack to a Kevin Costner romance, received nul points and placed absolute last, disqualifying Lithuania from the next year’s contest and prophesying the three decades to come. (I count disqualification as a second loss rather than a continuation of the first loss. I also count withdrawals as losses.)

Lithuania has lost the Eurovision Song Contest thirty times. The first loss, in 1994, was awarded to Ovidijus Vysniauskas’ « Lopšinė mylimai » (Lullaby for my lover). The ballad about a secret love, worthy of a soundtrack to a Kevin Costner romance, received nul points and placed absolute last, disqualifying Lithuania from the next year’s contest and prophesying the three decades to come. (I count disqualification as a second loss rather than a continuation of the first loss. I also count withdrawals as losses.) Since 2000, the world has experienced

Since 2000, the world has experienced  Interstate 35 through Austin, Texas, is the most congested stretch of road in the fastest-growing city in one of the sprawliest states in the country.

Interstate 35 through Austin, Texas, is the most congested stretch of road in the fastest-growing city in one of the sprawliest states in the country. LAHIRI

LAHIRI T

T