In late 1960s, perhaps spring of 1968 or 1969, Sidney Morgenbesser taught the first class on Marx to be offered by Columbia’s philosophy department. Sidney’s take was in the spirit of the later to develop analytic Marxism, meaning he read Marx through the lenses of methodological individualism, a rationality assumption, a search for microfoundations, especially for historical materialism, and a rejection of any hint of functional explanation. (He told me this story because I was sitting in on Jon Elster’s class on rational choice.) A junior faculty member (“…then he was to left of me, now he’s to the right of me…” was how Sidney described him) sat in on the class. The spring passed without the colleague making any comment at all in or about the class. During the summer, the two were having lunch, and Sidney who had been wondering about his colleague’s opinion about the class asked point blank what he thought of it. His colleague looked up and said, “Sidney, that was the best class on David Hume I have ever taken.”

In late 1960s, perhaps spring of 1968 or 1969, Sidney Morgenbesser taught the first class on Marx to be offered by Columbia’s philosophy department. Sidney’s take was in the spirit of the later to develop analytic Marxism, meaning he read Marx through the lenses of methodological individualism, a rationality assumption, a search for microfoundations, especially for historical materialism, and a rejection of any hint of functional explanation. (He told me this story because I was sitting in on Jon Elster’s class on rational choice.) A junior faculty member (“…then he was to left of me, now he’s to the right of me…” was how Sidney described him) sat in on the class. The spring passed without the colleague making any comment at all in or about the class. During the summer, the two were having lunch, and Sidney who had been wondering about his colleague’s opinion about the class asked point blank what he thought of it. His colleague looked up and said, “Sidney, that was the best class on David Hume I have ever taken.”

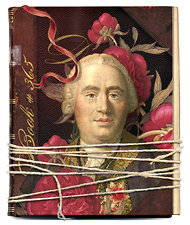

Hume’s and Marx’s birthdays are separated by only 2 days. Today is Hume’s 300th. Robert Zaretsky in the NYT on Hume’s reason and passion and love:

TODAY is the 300th birthday of David Hume, the most important philosopher ever to write in English, according to The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. The conferences being held on Hume this year in Austria, the Czech Republic, Russia, Finland and Brazil suggest that the encyclopedia’s claim is perhaps too modest.

Panelists will cite Hume’s seismic impact on epistemology, political theory, economics, historiography, aesthetics and religion, as well as his deep skepticism of the powers of reason. But chances are they won’t have much to say about Hume the man.

It’s not surprising; Hume was most concerned with the nature of knowledge, morality, causality — not with fashioning a philosophy for everyday life. And yet his life, like his work, does offer insights about how to live. Consider an episode in Hume’s life that reflects his most provocative and misunderstood claim: that reason is and always will be the slave to our passions. Predictably, it happened in Paris.

In 1761, Hippolyte de Saujon, the estranged wife of the Comte de Boufflers and celebrated mistress of the Prince de Conti, sent a fan letter to Hume. His best-selling “History of England,” she wrote, “enlightens the soul and fills the heart with sentiments of humanity and benevolence.” It must have been written by “some celestial being, free from human passions.”

From Edinburgh, the rotund and flustered Hume, long resigned to a bachelor’s life, thanked Mme. de Boufflers. “I have rusted amid books and study,” he wrote, and “been little engaged … in the pleasurable scenes of life.” But he would be pleased to meet her.

And so he did, two years later, when he was posted to the British Embassy in Paris. Boufflers and Hume quickly became intimate friends, visiting and writing to each other often. Hume soon confessed his attachment and his jealousy of Conti. Boufflers encouraged him, though no one knows how far: “Were I to add our deepened friendship to my other sources of happiness … I cannot conceive how I could ever complain of my destiny.”