Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Can Social Democracy Win Again? The tangled legacy of the Swedish experiment

Simon Torracinta in the Boston Review:

When Bernie Sanders was asked in a 2016 Democratic presidential debate what “democratic socialism” meant to him, he responded that we should “look to countries like Denmark, like Sweden and Norway.” Hillary Clinton was unequivocal in her reply: “We are not Denmark.” Yet Sanders kept the line, and his odes to the shining example of Nordic social democracy remained an exhaustive refrain throughout his 2016 and 2020 campaigns. The theme was unsurprising: ever since 1936, when Franklin Roosevelt hailed Sweden’s “middle way” between capitalism and communism, Scandinavia has been a fixture in the American left-liberal imaginary.

When Bernie Sanders was asked in a 2016 Democratic presidential debate what “democratic socialism” meant to him, he responded that we should “look to countries like Denmark, like Sweden and Norway.” Hillary Clinton was unequivocal in her reply: “We are not Denmark.” Yet Sanders kept the line, and his odes to the shining example of Nordic social democracy remained an exhaustive refrain throughout his 2016 and 2020 campaigns. The theme was unsurprising: ever since 1936, when Franklin Roosevelt hailed Sweden’s “middle way” between capitalism and communism, Scandinavia has been a fixture in the American left-liberal imaginary.

What’s not to like about Sweden?

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday Poem

Two Poems by Octavio Paz

……….. DAYBREAK

Hands and lips of wind

heart of water

………………….. eucalyptus

campground of the clouds

the life that is born everyday

the death that is born every life

I rub my eyes:

the sky walks the land

……….. NIGHTFALL

What sustains it,

half-open, the clarity of nightfall,

the light let loose in the gardens?

All the branches,

conquered by the weight of birds,

lean toward the darkness.

Pure, self-absorbed moments

still gleam

on the fences.

Receiving night,

the groves become

hushed fountains.

A bird falls,

the grass grows dark,

edges blur, lime is black,

the world is less credible.

Octavio Paz

from The Collected Poems, 1957-1987

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

In the Authoritarians’ New War on Ideas, Biology Might Be Next

C. Brandon Ogbunu in Undark Magazine:

In 2021, U.S. Sen.Ted Cruz compared critical race theory — an academic subfield that examines the role of racism in American institutions, laws, and policies — to the Ku Klux Klan, the most notorious homegrown terrorist organization in U.S. history. In doing so, he opened a playbook that resembles one put into practice by Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis and others: Attack ideas that are unfriendly to a narrow view of the world, and do so by eliminating them from our school curricula and public conversation. The movement against critical race theory has now swallowed up high school Advanced Placement African American Studies in several states and threatens the teaching of basic facts about U.S. history. And this movement has devolved from pundit tough talk into authoritarian policies to ban books, modify curricula, and threaten intellectual freedom across the country (and world).

In 2021, U.S. Sen.Ted Cruz compared critical race theory — an academic subfield that examines the role of racism in American institutions, laws, and policies — to the Ku Klux Klan, the most notorious homegrown terrorist organization in U.S. history. In doing so, he opened a playbook that resembles one put into practice by Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis and others: Attack ideas that are unfriendly to a narrow view of the world, and do so by eliminating them from our school curricula and public conversation. The movement against critical race theory has now swallowed up high school Advanced Placement African American Studies in several states and threatens the teaching of basic facts about U.S. history. And this movement has devolved from pundit tough talk into authoritarian policies to ban books, modify curricula, and threaten intellectual freedom across the country (and world).

By now, many realize that these policies are a harbinger of things to come — even for fields ostensibly unrelated to African American studies, like biology. Modern breakthroughs in biology are producing a picture of life that is increasingly incompatible with authoritarian preferences for neat boxes that dictate what people are and how they should behave.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How to win a Nobel prize

Smith and Ryan in Nature:

The Nobel prize has been awarded in three scientific fields — chemistry, physics and physiology or medicine — almost every year since 1901, barring some disruptions mostly due to wars. Nature crunched the data on the 346 prizes and their 646 winners (Nobel prizes can be shared by up to three people) to work out which characteristics can be reliably linked to medals.

The Nobel prize has been awarded in three scientific fields — chemistry, physics and physiology or medicine — almost every year since 1901, barring some disruptions mostly due to wars. Nature crunched the data on the 346 prizes and their 646 winners (Nobel prizes can be shared by up to three people) to work out which characteristics can be reliably linked to medals.

However, if you are a female scientist, your chances have improved in recent years. In the entire twentieth century, only 11 Nobel prizes were awarded to women. Since 2000, women have won another 15 prizes. You should expect to wait for your award — for about two decades after you produce your Nobel-worthy work1. So, on average, you should make a start on these projects by your 40s. The number of years between work and prize is lengthening as time goes by, with laureates before 1960 waiting an average of 14 years, and those honoured in the 2010s having to wait an average of 29 years. But there’s a time limit: prizes cannot be awarded posthumously.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday, October 2, 2024

Jennifer Ouellette chats with Ben Orlin about his new book, “Math for English Majors”

Jennifer Ouellette at Ars Technica:

Ars Technica: People who are not mathematically inclined usually see all those abstract symbols and their eyes glaze over. Let’s talk about the nature of symbols in math and why becoming more familiar with mathematical notation can help non-math people surmount that language barrier.

Ars Technica: People who are not mathematically inclined usually see all those abstract symbols and their eyes glaze over. Let’s talk about the nature of symbols in math and why becoming more familiar with mathematical notation can help non-math people surmount that language barrier.

Ben Orlin: It’s tricky. When I first became a teacher, I was mostly trying to push against students who’d only learned symbol manipulation procedures and didn’t have any sense of how to read and access the information behind them. It always mystified me: why do we teach that way? You end up with very bright, clever students, and all we’re giving them is hundreds of hours of practice in symbol manipulation. But what is a quadratic? They can’t really tell you.

One of the things I’ve gradually come to accept is that it’s almost baked into the language that mathematical notation has developed specifically for the purpose of manipulating it without thinking hard about it. If you’ve had the right set of experiences leading into that, that’s very convenient, because it means that when you sit down to solve a problem, you don’t have to solve it like Archimedes with lots of brilliant one-off steps where you just have gorgeous geometric intuition about everything. You can just be like, “Okay, I’m going to crank through the symbol manipulation procedures.” So there’s a real power in those procedures. They’re really valuable and important.

But if it’s all you have, then you’re doing a dance where you know the moves, but you’ve never heard the music.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Researchers are trying to find out: could we cool the planet using sea salt?

Quico Toro at Persuasion:

The climate debate is in a strange place. We’re told we face an epochal, civilization-ending calamity within our lifetimes. But when scientists bring up unconventional new ways of managing that risk, we’re told we mustn’t even talk about them.

The climate debate is in a strange place. We’re told we face an epochal, civilization-ending calamity within our lifetimes. But when scientists bring up unconventional new ways of managing that risk, we’re told we mustn’t even talk about them.

Why? Because, alas, some of their most promising ideas got slapped with the label “geoengineering”: a term so scary it seems to shut down people’s prefrontal cortex altogether.

The result is a weirdly misshapen public debate, where a strong taboo weighs over a whole branch of atmospheric science. Our climate debate refuses to acknowledge something top researchers now strongly suspect: that we could reverse global warming quickly and affordably using nothing scarier than sea salt.

The idea is called Marine Cloud Brightening (MCB). It would work by making clouds reflect more of the sun’s energy back out into space. As we speak, researchers are working on the basic science needed to figure out if it can really work at scale.

I’ve been talking to some of them.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Paul Bloom: The Surprising Science of Lasting Happiness

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

AI appears to do a better job of countering conspiracy theories than humans do

From The Economist:

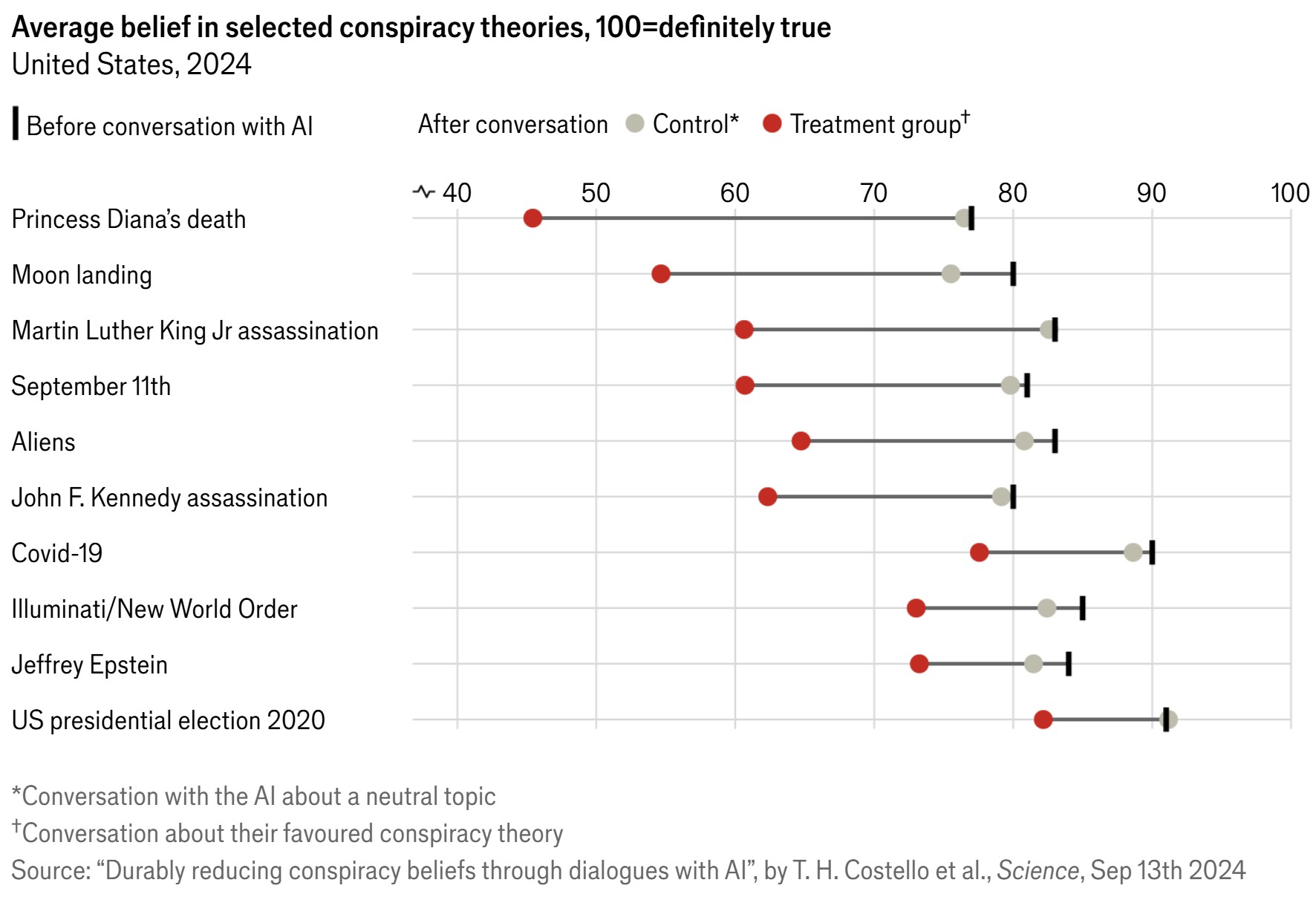

A new study published in Science, a journal, finds that artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots may be better than humans at convincing truthers to stop believing nonsense. A trio of researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Cornell University recruited nearly 2,200 self-declared conspiracy-theorists in America for a series of written conversations with GPT-4 Turbo, a chatbot. The subjects explained their theories and the evidence for them; the chatbot countered with facts.

To take one example, when a subject claimed that the federal government had orchestrated the attacks of September 11th 2001, and that the jet fuel from the crash was not hot enough to melt the steel girders supporting the Twin Towers, the bot answered like a cool-headed science teacher. “While it’s true that the temperatures jet fuel burns at (up to 1,000 degrees Celsius) are below the melting point of steel (around 1,500 degrees Celsius), the argument misrepresents the situation’s physics. Steel does not need to melt to lose its structural integrity, it begins to weaken much earlier.” By the end of the conservation the subject’s self-reported confidence in the theory fell by 60%.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

the matchup came down to Tim Walz’s record in Minnesota versus his opponent’s unfailing defense of Donald Trump

Benjamin Wallace-Wells in The New Yorker:

Vice-Presidential debates are normally for the archives: the transcript gets recorded and then filed away. Strain your memory and try to recall: Who won the debate between John Edwards and Dick Cheney? Biden-Ryan? Even Harris-Pence, just four years ago? In the rush of the Presidential race, these events were simply speed bumps. The best way to approach Tuesday night’s version was with a certain measure of historically earned skepticism. Was there any reason to think that this Vice-Presidential debate would actually matter—would even be remembered—by Election Day, now a little more than a month away, when so few have in the past?

Vice-Presidential debates are normally for the archives: the transcript gets recorded and then filed away. Strain your memory and try to recall: Who won the debate between John Edwards and Dick Cheney? Biden-Ryan? Even Harris-Pence, just four years ago? In the rush of the Presidential race, these events were simply speed bumps. The best way to approach Tuesday night’s version was with a certain measure of historically earned skepticism. Was there any reason to think that this Vice-Presidential debate would actually matter—would even be remembered—by Election Day, now a little more than a month away, when so few have in the past?

Maybe not. But during ninety remarkably fast-talking minutes in New York—verbally, both candidates are speed demons—the Ohio senator J. D. Vance moved the narrative of the race in a small but perceptible way toward the Republican side. Vance was first to every touchstone that mattered—the first to introduce himself personally to the American people and to bring up the meagre and pressured working-class circumstances in which he was raised, the first to insist that his was the ticket to favor “clean air” and “clean water,” the first to credit his running mate, Donald Trump, with an “economic boom unlike we’ve seen in a generation in this country.” His intent seemed simple—to persuade voters, who are broadly dissatisfied with the direction of the country, that the Democrats are largely responsible for it. But Vance also had an advantage in cunningness. The young senator even managed to turn around a question on family separation, one of the more reprehensible episodes of the Trump years. “Right now in this country . . . we have three hundred and twenty thousand children that the Department of Homeland Security has effectively lost,” he said. “The real family-separation crisis is unfortunately Kamala Harris’s wide-open southern border.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday Poem

Autumn Poem from Campbell, CA:

First rain since April and my small dog,

nose close to the ground, sniffs

his way about a New Eden –

telephone pole, his old stop, smells

fresh and new, the corner mailbox,

shiny again, gets a quick sniff

and a new pee. The grass has little

drops of water on it so his walk onto

the neighbor’s lawn for a poop is

at first tentative and exploratory.

I pick it up in a corner cut from my newspaper’s

plastic wrap, look about, think summer

here’s a dusty place. So, as the dog’s been

urging, I take a deep autumnal breath.

“We don’t do what we ought. We do what we can.”

Good words. Worth a second saying.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

AI and Scientists Face Off to See Who Can Come Up With the Best Ideas

Shelly Fan in Singularity Hub:

Scientific breakthroughs rely on decades of diligent work and expertise, sprinkled with flashes of ingenuity and, sometimes, serendipity. What if we could speed up this process?

Scientific breakthroughs rely on decades of diligent work and expertise, sprinkled with flashes of ingenuity and, sometimes, serendipity. What if we could speed up this process?

Creativity is crucial when exploring new scientific ideas. It doesn’t come out of the blue: Scientists spend decades learning about their field. Each piece of information is like a puzzle piece that can be reshuffled into a new theory—for example, how different anti-aging treatments converge or how the immune system regulates dementia or cancer to develop new therapies.

AI tools could accelerate this. In a preprint study, a team from Stanford pitted a large language model (LLM)—the type of algorithm behind ChatGPT—against human experts in the generation of novel ideas over a range of research topics in artificial intelligence. Each idea was evaluated by a panel of human experts who didn’t know if it came from AI or a human. Overall, ideas generated by AI were more out-of-the-box than those by human experts. They were also rated less likely to be feasible. That’s not necessarily a problem. New ideas always come with risks. In a way, the AI reasoned like human scientists willing to try out ideas with high stakes and high rewards, proposing ideas based on previous research, but just a bit more creative. The study, almost a year long, is one of the biggest yet to vet LLMs for their research potential.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday, October 1, 2024

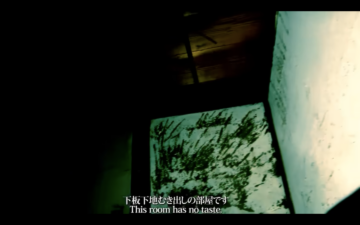

Nonfictional works designed “with the intention of upsetting, disturbing, or confusing the audience”

Clayton Purdom at the Los Angeles Review of Books:

The first time I tried to write this essay, I failed. It was the middle of the pandemic—a time in which uncountable numbers of introspective personal essays were written to no apparent end—and I watched Sans Soleil, director Chris Marker’s dreamlike 1983 travelogue. I was working at a marketing agency at the time, suffusing strategic briefs with literary ambition, and something about the way Marker’s film faded from documentary to sci-fi to philosophical reverie ignited long-dormant neurons in my brain. Sleeper cells dissatisfied with a life in service of internet content and client work assembled. They blew up access tunnels and sabotaged meeting preparation protocols. I wrote something big and haunted about my experience as a writer and intended to publish it, in an act of vainglorious career suicide, on LinkedIn.

The first time I tried to write this essay, I failed. It was the middle of the pandemic—a time in which uncountable numbers of introspective personal essays were written to no apparent end—and I watched Sans Soleil, director Chris Marker’s dreamlike 1983 travelogue. I was working at a marketing agency at the time, suffusing strategic briefs with literary ambition, and something about the way Marker’s film faded from documentary to sci-fi to philosophical reverie ignited long-dormant neurons in my brain. Sleeper cells dissatisfied with a life in service of internet content and client work assembled. They blew up access tunnels and sabotaged meeting preparation protocols. I wrote something big and haunted about my experience as a writer and intended to publish it, in an act of vainglorious career suicide, on LinkedIn.

This is not that essay, which I ended up storing in the cloud, untouched and perfect. Maybe I just lost the nerve. I came to view the entire months-long ordeal as merely a romantic obsession with Sans Soleil, the sort of honeymooning that occurs with a piece of art only a handful of times in life, in which old tastes are dramatically reordered and new, long-lasting obsessions emerge. That essay, that romance, hung over me as I logged back in to Slack. And yet something was different. The strategic briefs shifted beneath my gaze now. I saw Sans Soleil’s borderless spirit everywhere, and came to see it as representative of an aesthetic thread that named itself outside of my will, its name slowly infecting my thoughts over the years since.

I call it weird nonfiction: creative work that presents itself as journalism or nonfiction but introduces fictional elements with the intention of upsetting, disturbing, or confusing the audience.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Intricate Connections Between Humans and Nature

Richard Schiffman at Undark:

Peter Godfrey-Smith does not use the word miracle in the title of his ambitious new book, “Living on Earth: Forest, Corals, Consciousness and the Making of the World,” but there is scarcely a page that does not recount one. His subject is the astounding creativity of life, not just to evolve ever-new forms, but to continually remake the planet that hosts it.

Peter Godfrey-Smith does not use the word miracle in the title of his ambitious new book, “Living on Earth: Forest, Corals, Consciousness and the Making of the World,” but there is scarcely a page that does not recount one. His subject is the astounding creativity of life, not just to evolve ever-new forms, but to continually remake the planet that hosts it.

Godfrey-Smith, a professor in the School of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Sydney, moves dizzyingly from the latest developments in neurology to the nature of human language and of consciousness itself. The core story traces life’s epic journey from cyanobacteria, which were amongst the first photosynthesizing plants, to increasingly complex multicellular plants, which contributed to creating an oxygen-rich atmosphere, which in turn paved the way for the evolution of oxygen breathing animals like ourselves.

It is “a history of organisms as causes, rather than evolutionary products,” he writes, presenting “a dynamic picture of the Earth, a picture of an Earth continually changing because of what living things do.”

Homo sapiens, relative latecomers to life’s party, are only the latest in a long line of species that have cleverly engineered the environment to meet their own needs.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

I used to hate QR codes, but they’re actually genius

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Terry Eagleton on Fredric Jameson (1934-2024)

Terry Eagleton at Verso Books:

I first met Fred Jameson in 1976, when he invited me to teach his graduate students at the University of California, San Diego. Before then I had known of his existence only through the stunning Marxism and Form, published five years earlier, a set of coruscating accounts of thinkers such as Lukacs, Benjamin, Adorno, Ernst Bloch and others. The book’s very title throws down the gauntlet to a dreary lineage of vulgar Marxist criticism. It also deals with a number of German works, some of them bristling with difficulties, which had not then been translated into English.

I first met Fred Jameson in 1976, when he invited me to teach his graduate students at the University of California, San Diego. Before then I had known of his existence only through the stunning Marxism and Form, published five years earlier, a set of coruscating accounts of thinkers such as Lukacs, Benjamin, Adorno, Ernst Bloch and others. The book’s very title throws down the gauntlet to a dreary lineage of vulgar Marxist criticism. It also deals with a number of German works, some of them bristling with difficulties, which had not then been translated into English.

I was convinced, then, that the name Fredric Jameson was probably a pseudonym for Hans-Georg Kaufmann or Karl Gluckstein, a refugee from Mitteleuropa holed up in southern California. The man I met, however, who greeted me with a brusqueness which I later learned was shyness, was as American as Tim Walz, though one suspects that Walz doesn’t slink away to read the latest Czech fiction over a glass of wine. He used expressions like ‘look it’ and ‘holy shit’, wore denim jeans, enjoyed eating turf ‘n surf and was clearly uncomfortable in the presence of patrician French intellectuals, much preferring the genial, outgoing Umberto Eco. All this was authentic enough; but he was also an intellectual in a civilisation in which such creatures are well advised to appear in disguise.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

On The Cinema Of Robert Beavers

Though the history of experimental film is rife with iconoclastic visionaries, Robert Beavers somehow remains one of its under-sung heroes. Together with his partner, Gregory Markopoulos (1928–92), Beavers developed an approach to cinema defined by its singular and uncompromising rigor, yielding a body of work celebrated as much for its poetic beauty as its complex formal investigation of the filmmaking apparatus. While continuing to make films to this day, Beavers also helms the Temenos, an open-air theatre in Lyssaraia Greece, dedicated to screenings of Markopoulos’s sprawling magnum opus, Eniaios (1947–91).

Though the history of experimental film is rife with iconoclastic visionaries, Robert Beavers somehow remains one of its under-sung heroes. Together with his partner, Gregory Markopoulos (1928–92), Beavers developed an approach to cinema defined by its singular and uncompromising rigor, yielding a body of work celebrated as much for its poetic beauty as its complex formal investigation of the filmmaking apparatus. While continuing to make films to this day, Beavers also helms the Temenos, an open-air theatre in Lyssaraia Greece, dedicated to screenings of Markopoulos’s sprawling magnum opus, Eniaios (1947–91).

From September 26 to 29, 2024, New York’s Anthology Film Archives has programmed a retrospective of Beavers’s films, giving American audiences a rare opportunity to see his work.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

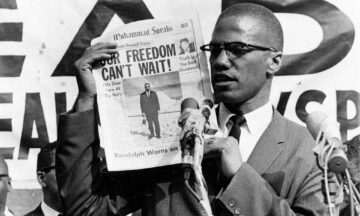

The Strangers – inside the minds of extraordinary Black men

Christenna Fryar in The Guardian:

If there is one thing that all historians must make peace with, it is that it is hard, often impossible, to know how people in the past felt. Historical fiction has the upper hand in its ability to render the complex yet plausible emotions and motivations of historical figures. Categorised by the publisher as creative nonfiction, Ekow Eshun’s The Strangers is foremost a work of imagination that sits somewhere between history and fiction. In lyrical prose, it presents the lives of five Black men: Ira Aldridge, 19th-century actor and playwright; Matthew Henson, polar explorer; Frantz Fanon, psychiatrist and political philosopher; footballer Justin Fashanu; and Malcolm X. Through them, the book moves from the early-19th century to the late-20th. More connects these men than race. Eshun selects moments when each one is in an exile of some kind, geographically and emotionally far away from what they once knew, questioning their place in the world, estranged in some way from their previous life.

If there is one thing that all historians must make peace with, it is that it is hard, often impossible, to know how people in the past felt. Historical fiction has the upper hand in its ability to render the complex yet plausible emotions and motivations of historical figures. Categorised by the publisher as creative nonfiction, Ekow Eshun’s The Strangers is foremost a work of imagination that sits somewhere between history and fiction. In lyrical prose, it presents the lives of five Black men: Ira Aldridge, 19th-century actor and playwright; Matthew Henson, polar explorer; Frantz Fanon, psychiatrist and political philosopher; footballer Justin Fashanu; and Malcolm X. Through them, the book moves from the early-19th century to the late-20th. More connects these men than race. Eshun selects moments when each one is in an exile of some kind, geographically and emotionally far away from what they once knew, questioning their place in the world, estranged in some way from their previous life.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Genetic Engineering Hides Donor Organs from Host Immune System

Hannah Thomasy in The Scientist:

Worldwide, more than three million people lose their lives each year to lung-damaging conditions like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or cystic fibrosis.1 In contrast, fewer than 5,000 individuals per year are fortunate enough to receive life-saving lung transplants.2 Transplant recipients still face many challenges, however, including a lifetime of immunosuppressant medications with potentially severe side effects and a more than 40 percent transplant failure rate in the first five years.3

Worldwide, more than three million people lose their lives each year to lung-damaging conditions like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or cystic fibrosis.1 In contrast, fewer than 5,000 individuals per year are fortunate enough to receive life-saving lung transplants.2 Transplant recipients still face many challenges, however, including a lifetime of immunosuppressant medications with potentially severe side effects and a more than 40 percent transplant failure rate in the first five years.3

In a recent study in Science Translational Medicine, transplantation immunologist Rainer Blasczyk and his team at the Hannover Medical School presented a potential solution to these problems in a minipig model.4 Instead of administering immunosuppressants, which Blasczyk likened to blinding the patient’s immune system, leaving the individual vulnerable to infections and even certain types of cancer, the researchers suppressed key immune proteins in the donor lung, rendering it immunologically invisible.5 Modifying the organ instead of the recipient isn’t a new idea, but it is an important one, said Jeffrey Platt, a transplantation biologist at the University of Michigan Medical School who was not involved in this work. “If you can introduce something that will affect the donor organ, then you can preserve the immune system of the recipient. And in lung transplantation, that’s really important because the lung is one of the first targets of infectious organisms.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Robert Beavers – The Hedge Theater

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.