John Naughton in The Guardian:

In 2011, the psychologist (and Nobel laureate) Daniel Kahneman proposed that we humans are bimodal animals capable only of two modes of thought. One (which he called “System 1”) is fast, instinctive and emotional. The other (“System 2”) is slower, more deliberative and more logical. The first doubtless evolved when we were hunter-gatherers, and served us well in that reality. The second, involving slow, effortful, infrequent, logical, calculating, conscious thought, came later, as societies became more complex and uncertainty became an integral part of the human condition. Uncertainty is, says David Spiegelhalter, “all about us, but, like the air we breathe, it tends to remain unexamined”. Which is why he wrote a book about how to live with it.

In 2011, the psychologist (and Nobel laureate) Daniel Kahneman proposed that we humans are bimodal animals capable only of two modes of thought. One (which he called “System 1”) is fast, instinctive and emotional. The other (“System 2”) is slower, more deliberative and more logical. The first doubtless evolved when we were hunter-gatherers, and served us well in that reality. The second, involving slow, effortful, infrequent, logical, calculating, conscious thought, came later, as societies became more complex and uncertainty became an integral part of the human condition. Uncertainty is, says David Spiegelhalter, “all about us, but, like the air we breathe, it tends to remain unexamined”. Which is why he wrote a book about how to live with it.

Uncertainty, in Spiegelhalter’s view, is a relationship between an individual and the outside world. And, because of that, our personal judgments play an essential role whenever we are faced with it, “whether we are thinking about our lives, weighing up what people tell us, or doing scientific research”. And tolerance of uncertainty varies hugely among people: some are excited by unpredictability, while others are crippled by anxiety.

When dealing with uncertainty, Spiegelhalter argues, Kahneman’s System 1 is bad news. It “tends towards overconfidence, neglects important background information, ignores the quantity and quality of the evidence, is unduly influenced by how the issue is posed, takes too much notice of rare but dramatic events, and suppresses doubt”.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

For a while there in the late nineties, it seemed to me like every other book of poetry that I flipped open in the bookstore was prefaced by an austere epigraph from the writings of Ludwig Wittgenstein. Plato, Rousseau, Nietzsche, Sartre, and Wittgenstein—for all their many differences—enjoy a special status as “poets’ philosophers” in the annals of literary history. Other lofty thinkers fly under poets’ collective radar; I have yet to come across a volume of verse prefaced by a quotation from David Hume. What makes some philosophers, and not others, into poets’ philosophers remains a mystery to me. But I’ve never really thought of Hannah Arendt as one of them.

For a while there in the late nineties, it seemed to me like every other book of poetry that I flipped open in the bookstore was prefaced by an austere epigraph from the writings of Ludwig Wittgenstein. Plato, Rousseau, Nietzsche, Sartre, and Wittgenstein—for all their many differences—enjoy a special status as “poets’ philosophers” in the annals of literary history. Other lofty thinkers fly under poets’ collective radar; I have yet to come across a volume of verse prefaced by a quotation from David Hume. What makes some philosophers, and not others, into poets’ philosophers remains a mystery to me. But I’ve never really thought of Hannah Arendt as one of them. If a change of style is a change of subject, as Wallace Stevens averred, then a change of syntax is a change of meaning. Word order is, if not all, then nine tenths. I exaggerate, but I do so advisedly, as a corrective to the overemphasis on word choice, the unjust rule of the mot juste (recall here the old saying about the difference between lightning and a lightning bug) that dominates, to the detriment of other concerns, contemporary literature and creative writing. At times, this passion for the right—or the unusual—word reaps dividends; at others, it merely produces an uncalled-for flood of verbed nouns, portmanteaus, adjectives wrenched out of joint.

If a change of style is a change of subject, as Wallace Stevens averred, then a change of syntax is a change of meaning. Word order is, if not all, then nine tenths. I exaggerate, but I do so advisedly, as a corrective to the overemphasis on word choice, the unjust rule of the mot juste (recall here the old saying about the difference between lightning and a lightning bug) that dominates, to the detriment of other concerns, contemporary literature and creative writing. At times, this passion for the right—or the unusual—word reaps dividends; at others, it merely produces an uncalled-for flood of verbed nouns, portmanteaus, adjectives wrenched out of joint. I

I The key structure of the doctrine of nuclear deterrence is audible in the September 4, 2024, speech by U.S. Deputy Under Secretary of Defense Cara Abercrombie: “Any nuclear attack by the DPRK against the United States or its allies and partners is unacceptable and will result in the end of that regime.” The doctrine, which the United States has embraced since the Cold War, aims to prevent an adversary from launching a nuclear weapon by assuring that any first strike will be followed by a retaliatory second strike, whose effects will equal or exceed the original damage and may eliminate the adversary altogether. This annihilating reflex of deterrence is equally audible in the quiet words of the Department of Defense in its web page on “America’s Nuclear Triad,” its sea-based, land-based, and air-based delivery platforms: “The triad, along with assigned forces, provide 24/7 deterrence to prevent catastrophic actions from our adversaries and they stand ready, if necessary, to deliver a decisive response, anywhere, anytime.”

The key structure of the doctrine of nuclear deterrence is audible in the September 4, 2024, speech by U.S. Deputy Under Secretary of Defense Cara Abercrombie: “Any nuclear attack by the DPRK against the United States or its allies and partners is unacceptable and will result in the end of that regime.” The doctrine, which the United States has embraced since the Cold War, aims to prevent an adversary from launching a nuclear weapon by assuring that any first strike will be followed by a retaliatory second strike, whose effects will equal or exceed the original damage and may eliminate the adversary altogether. This annihilating reflex of deterrence is equally audible in the quiet words of the Department of Defense in its web page on “America’s Nuclear Triad,” its sea-based, land-based, and air-based delivery platforms: “The triad, along with assigned forces, provide 24/7 deterrence to prevent catastrophic actions from our adversaries and they stand ready, if necessary, to deliver a decisive response, anywhere, anytime.” Difficult relationships between fathers and sons have been fodder for writers for millennia. Sometimes these relationships are simply power struggles, as in so many

Difficult relationships between fathers and sons have been fodder for writers for millennia. Sometimes these relationships are simply power struggles, as in so many  The early days of the pandemic were a complicated time for a lot of couples.

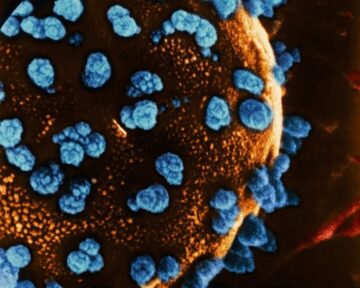

The early days of the pandemic were a complicated time for a lot of couples. A 25-year-old woman with type 1 diabetes started producing her own insulin less than three months after receiving a transplant of reprogrammed stem cells

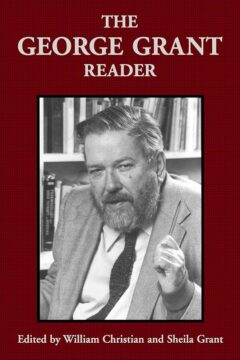

A 25-year-old woman with type 1 diabetes started producing her own insulin less than three months after receiving a transplant of reprogrammed stem cells George Parkin Grant, who died in 1988 at the age of 69, was world-famous in Canada—at least, that was the jest frequently made at the philosopher’s expense. The joke reflected his status as a public intellectual who made frequent appearances on Canadian Broadcast Corporation radio programs but never attracted much attention south of the 49th parallel. There are many reasons for his obscurity outside his home country, but one cause was surely his intense Canadian nationalism, coupled with his outspoken criticism of the form of liberalism he saw embodied in the hegemon to the south.

George Parkin Grant, who died in 1988 at the age of 69, was world-famous in Canada—at least, that was the jest frequently made at the philosopher’s expense. The joke reflected his status as a public intellectual who made frequent appearances on Canadian Broadcast Corporation radio programs but never attracted much attention south of the 49th parallel. There are many reasons for his obscurity outside his home country, but one cause was surely his intense Canadian nationalism, coupled with his outspoken criticism of the form of liberalism he saw embodied in the hegemon to the south. In the chilling speech he gives at the end of the film Margin Call, Jeremy Irons says that no one should say they believe in equality, because no one really thinks it exists: The very idea camouflages the endurance of hierarchy in an essentially unchanging form. “It’s certainly no different today than it’s ever been,” he explains to an underling. “There have always been and there always will be the same percentage of winners and losers….

In the chilling speech he gives at the end of the film Margin Call, Jeremy Irons says that no one should say they believe in equality, because no one really thinks it exists: The very idea camouflages the endurance of hierarchy in an essentially unchanging form. “It’s certainly no different today than it’s ever been,” he explains to an underling. “There have always been and there always will be the same percentage of winners and losers…. Zadie Smith did not understand why anyone would be interested in her bookshelves.

Zadie Smith did not understand why anyone would be interested in her bookshelves.