Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Happiness swings votes – and America’s current mood could scramble expectations of young and old voters

Carol Bishop Mills in The Conversation:

I am an interpersonal communication researcher and the co-founder and co-director of the Florida Atlantic University Mainstreet Political Communication Lab. Our lab investigates and analyzes public opinion and political trends nationwide. With the upcoming election, I’ve been specifically examining the potential influence of happiness on voting patterns.

I am an interpersonal communication researcher and the co-founder and co-director of the Florida Atlantic University Mainstreet Political Communication Lab. Our lab investigates and analyzes public opinion and political trends nationwide. With the upcoming election, I’ve been specifically examining the potential influence of happiness on voting patterns.

Research worldwide indicates that happy people prefer keeping things the same, and they tend to vote for the incumbent in political elections. Voters who aren’t as happy are more open to anti-establishment candidates, seeing the government as a source of their discontent.

These findings may help to explain the Democratic Party’s waning support among young people.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Husserl’s Phenomenology – Marvin Farber (1959)

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Why Can’t My Son Vote?

Paul Collins at The Believer:

I suppose I’d once imagined the history of American voting rights as a steady march toward greater equality. But the more you look at American suffrage, the more it feels like a visit to the Winchester Mystery House: there are bafflingly constructed chambers, grand and glorious halls, and stairways that lead nowhere. To begin with, there’s no specific right-to-vote clause in our Constitution, so the US lacks what is now an obvious provision for a modern democracy to include. Instead, there are the famed inalienable rights, and descriptions of how elections work, which imply and essentially necessitate a freely voting populace; plus there are many subsequent amendments, federal acts, and court decisions. But otherwise the Constitution hands over voting and voter qualifications to states. For many decades, states didn’t have laws barring the intellectually disabled from voting: they didn’t need to, because they allowed hardly any citizens to vote. For the election of George Washington in 1788 and 1789, Massachusetts required that voters be men aged twenty-one or older, and possessing an estate worth at least sixty British pounds. Most states had similar laws. That’s why, in a country of nearly four million people, just 43,782 votes were cast—slightly more than 1 percent of the population.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Book Review: The Intricate Connections Between Humans and Nature

Richard Schifman in Undark Magazine:

Peter Godfrey-Smith does not use the word miracle in the title of his ambitious new book, “Living on Earth: Forest, Corals, Consciousness and the Making of the World,” but there is scarcely a page that does not recount one. His subject is the astounding creativity of life, not just to evolve ever-new forms, but to continually remake the planet that hosts it.

Peter Godfrey-Smith does not use the word miracle in the title of his ambitious new book, “Living on Earth: Forest, Corals, Consciousness and the Making of the World,” but there is scarcely a page that does not recount one. His subject is the astounding creativity of life, not just to evolve ever-new forms, but to continually remake the planet that hosts it.

Godfrey-Smith, a professor in the School of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Sydney, moves dizzyingly from the latest developments in neurology to the nature of human language and of consciousness itself. The core story traces life’s epic journey from cyanobacteria, which were amongst the first photosynthesizing plants, to increasingly complex multicellular plants, which contributed to creating an oxygen-rich atmosphere, which in turn paved the way for the evolution of oxygen breathing animals like ourselves.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Both My Abortions Were Necessary. Only One Gets Sympathy

Sarah Harrison in The New York Times:

Here are two abortion stories. Both are mine. Both came with heartache and upheaval — and both prevented heartache and upheaval. One was an experience common to many abortion patients, but one that people often look on with disdain. The other was the sort that generally garners public sympathy. I wish they both did.

Here are two abortion stories. Both are mine. Both came with heartache and upheaval — and both prevented heartache and upheaval. One was an experience common to many abortion patients, but one that people often look on with disdain. The other was the sort that generally garners public sympathy. I wish they both did.

I had my first abortion one day after I turned 28. I was a single mom to a 5-year-old daughter. We lived in Washington, D.C., in a one-bedroom basement apartment. I was a recent law-school graduate, studying for the bar exam, living off a loan and small scholarship, and working a full-time unpaid internship hoping it might open doors to job opportunities. I knew I could not raise another child while being the mother I wanted to be for my daughter, or while pursuing the career I wanted in public service. It’s the kind of story that people tend to judge rather than champion.

My second abortion was this past November. This time I was married and happily and intentionally pregnant. The only surprise was that it was twins. Now, 37 years old, I had routine prenatal testing — which revealed that fetus B had Trisomy 18, a fatal fetal anomaly. I knew that continuing the unviable pregnancy of fetus B would have put fetus A, and me, at a high risk of serious complications, including miscarriage, stillbirth and preterm birth. My husband and I were heartbroken. We knew there was only one way to protect fetus A and myself. But we live in Texas. And because of our state’s abortion ban, I had to travel to Colorado for abortion care. The Texas ban provides no exception for an abortion in the case of fatal fetal abnormalities — even for the purpose of protecting a second, healthy fetus.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday Poem

The Skin Inside

Out there past the last old windmill

and the last stagnant canal—

the no-man’s land of western Dithmarschen—

cabbage and horseradish in rows of staggering accuracy

stretching all the way out to the frigid

gray-brown waters of the North Sea—

hard-hatted Day-Glo-vested workers perched high

in the new steel pylons rigging cables to connect

off-shore wind parks with the ant-hills of civilization—

I’ve got one hand on the steering wheel,

the other on the dial cranking up King Tubby’s

“A Better Version” nice and loud while waiting

most likely in vain in some kind of cerebral limbo

for the old symbolism to morph into

an entirely new vernacular—an idiom of sheer imagery

in which the images themselves have

no significance whatsoever but struggle nonetheless

to articulate the meaning of meaning—

a hall of mirrors where purity reigns

and the algorithm of death can no longer find you—

and if it’s a truth to be realized that your body is not

your own, then it must be a delegated image of heaven,

while the skin inside has a luster all its own,

reflecting back the warm glow from within.

by Mark Terrill

from Empty Mirror

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Sex Work Memoir Comes Of Age

Sascha Cohen at The Baffler:

“People look for themselves in books and movies,” Lily Burana wrote in her 2001 memoir Strip City. “But for strippers, there is no Giovanni’s Room . . . no Well of Loneliness.” Times have changed. Over the past two decades, dozens of writers with experience in the sex industry—former strippers, escorts, porn performers, and dominatrices—have built a canon of their own. As masters of carnality (what Mary Karr describes as the most “primal and necessary” element of memoir), sex workers are well suited for the genre. Despite the accusation regularly lobbed by sex industry abolitionists that the prostitute “sells their body,” they in fact sell a fantasy, which is just another word for a story. “Performing intimacy is also work I know how to do,” writes conceptual artist and escort Sophia Giovannitti in her 2023 book Working Girl of the similarities between her creative and erotic labor. “The studied reveal is the specialty of the whore.”

“People look for themselves in books and movies,” Lily Burana wrote in her 2001 memoir Strip City. “But for strippers, there is no Giovanni’s Room . . . no Well of Loneliness.” Times have changed. Over the past two decades, dozens of writers with experience in the sex industry—former strippers, escorts, porn performers, and dominatrices—have built a canon of their own. As masters of carnality (what Mary Karr describes as the most “primal and necessary” element of memoir), sex workers are well suited for the genre. Despite the accusation regularly lobbed by sex industry abolitionists that the prostitute “sells their body,” they in fact sell a fantasy, which is just another word for a story. “Performing intimacy is also work I know how to do,” writes conceptual artist and escort Sophia Giovannitti in her 2023 book Working Girl of the similarities between her creative and erotic labor. “The studied reveal is the specialty of the whore.”

Although sex worker memoirs now appear in greater numbers compared to when Burana’s book came out over twenty years ago, they tend to be published by indie presses rather than the Big Five, and often generate less attention than the fictions of prostitution found in novels written by civilians; I’m thinking of Emma Cline’s The Guest, Arthur Golden’s Memoirs of a Geisha, and, further back, Truman Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Theodore Dreiser’s Sister Carrie, and Émile Zola’s Nana.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday, September 24, 2024

William Blake’s Dark Vision Of London

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Michel Houellebecq Vents Again

Oskar Oprey at Artforum:

I THINK I’M GOING TO LEARN FRENCH, if only to keep up with Michel Houellebecq. The aging bad boy of letters has been embroiled in a fresh crop of scandals these past few years, the plotlines worthy of an X-rated soap opera on Canal+. First there’s his legal battle with Dutch art collective KIRAC—they collaborated on a pornographic film project together, in which audiences would have seen Houellebecq having sex with women other than his wife. He seems to have gotten cold feet after the trailer was teased, even though he’d already signed a release form. Then there are the accusations of plagiarism surrounding his 2015 novel Submission, which imagined France embracing Sharia law. Speaking of which, Houellebecq has also apologized for offensive comments he made in an interview published in Front Populaire. Meanwhile, Meta’s AI tool has refused point-blank to write in his style. A short memoir titled A Few Months of My Life (Quelques mois dans ma vie: Octobre 2022–Mars 2023) was published last year, in which Houellebecq gave his account regarding some of these stories. Sadly, this has yet to be translated into English. Which brings me to my main reason for taking French lessons: I want to read his damn books as soon as they hit the shelves! His latest novel, Annihilation, was originally released in France in January 2022; the English translation was subsequently mired in a two-and-a-half-year delay.

I THINK I’M GOING TO LEARN FRENCH, if only to keep up with Michel Houellebecq. The aging bad boy of letters has been embroiled in a fresh crop of scandals these past few years, the plotlines worthy of an X-rated soap opera on Canal+. First there’s his legal battle with Dutch art collective KIRAC—they collaborated on a pornographic film project together, in which audiences would have seen Houellebecq having sex with women other than his wife. He seems to have gotten cold feet after the trailer was teased, even though he’d already signed a release form. Then there are the accusations of plagiarism surrounding his 2015 novel Submission, which imagined France embracing Sharia law. Speaking of which, Houellebecq has also apologized for offensive comments he made in an interview published in Front Populaire. Meanwhile, Meta’s AI tool has refused point-blank to write in his style. A short memoir titled A Few Months of My Life (Quelques mois dans ma vie: Octobre 2022–Mars 2023) was published last year, in which Houellebecq gave his account regarding some of these stories. Sadly, this has yet to be translated into English. Which brings me to my main reason for taking French lessons: I want to read his damn books as soon as they hit the shelves! His latest novel, Annihilation, was originally released in France in January 2022; the English translation was subsequently mired in a two-and-a-half-year delay.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Krishna Goes To Sea

John Keay at Literary Review:

After writing a string of award-winning books on India, the historian and literary phenomenon William Dalrymple has forsaken the glamour of the Mughals and the murky dealings of the English East India Company to look beyond the Indian subcontinent and make the case for the existence of a wider, pre-Islamic ‘Indosphere’. His aim in The Golden Road is, he says, ‘to highlight India’s often forgotten position as a crucial economic fulcrum, and civilisational engine, at the heart of the ancient and early medieval worlds and as one of the main motors of global trade and cultural transmission in early world history, fully on a par with and equal to China.’

After writing a string of award-winning books on India, the historian and literary phenomenon William Dalrymple has forsaken the glamour of the Mughals and the murky dealings of the English East India Company to look beyond the Indian subcontinent and make the case for the existence of a wider, pre-Islamic ‘Indosphere’. His aim in The Golden Road is, he says, ‘to highlight India’s often forgotten position as a crucial economic fulcrum, and civilisational engine, at the heart of the ancient and early medieval worlds and as one of the main motors of global trade and cultural transmission in early world history, fully on a par with and equal to China.’

This will go down well in an assertive and increasingly Sinophobic India, where Dalrymple is largely based. It will in particular be music to the ears of the nation’s ubiquitous technocrats. It also chimes with the marginalisation of Indian Muslims and the ‘saffron-washing’ of the country’s Islamic heritage by Hindu zealots of Narendra Modi’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

more here.

Zadie Smith on Populists, Frauds and Flip Phones

Ezra Klein in the New York Times:

Sometimes you stumble across a line in a book and think, “Yeah, that’s exactly how that feels.” I had that moment reading the introduction to Zadie Smith’s 2018 book of essays,

Sometimes you stumble across a line in a book and think, “Yeah, that’s exactly how that feels.” I had that moment reading the introduction to Zadie Smith’s 2018 book of essays,

“Feel Free.” She’s talking about the political stakes of that period — Brexit in Britain, Donald Trump here — and the way you could feel it changing people.

She writes: “Millions of more or less amorphous selves will now necessarily find themselves solidifying into protesters, activists, marchers, voters, firebrands, impeachers, lobbyists, soldiers, champions, defenders, historians, experts, critics. You can’t fight fire with air. But equally you can’t fight for a freedom you’ve forgotten how to identify.”

What Smith is describing felt so familiar. I see it so often in myself and people around me. And yet you rarely hear it talked about — that moment when politics feels like it demands we put aside our internal conflict, our uncertainty, and solidify ourselves into what the cause or the moment needs us to be, as if curiosity were a luxury or a decadence suited only to peacetime.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

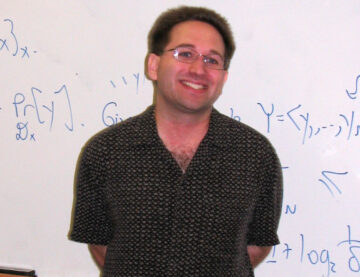

Quantum Computing: Between Hope and Hype

Scott Aaronson at Shtetl-Optimized:

When Rafi invited me to open this event, it sounded like he wanted big-picture pontification more than technical results, which is just as well, since I’m getting old for the latter. Also, I’m just now getting back into quantum computing after a two-year leave at OpenAI to think about the theoretical foundations of AI safety. Luckily for me, that was a relaxing experience, since not much happened in AI these past two years. [Pause for laughs] So then, did anything happen in quantum computing while I was away?

When Rafi invited me to open this event, it sounded like he wanted big-picture pontification more than technical results, which is just as well, since I’m getting old for the latter. Also, I’m just now getting back into quantum computing after a two-year leave at OpenAI to think about the theoretical foundations of AI safety. Luckily for me, that was a relaxing experience, since not much happened in AI these past two years. [Pause for laughs] So then, did anything happen in quantum computing while I was away?

This, of course, has been an extraordinary time for both quantum computing and AI, and not only because the two fields were mentioned for the first time in an American presidential debate (along with, I think, the problem of immigrants eating pets). But it’s extraordinary for quantum computing and for AI in very different ways. In AI, practice is wildly ahead of theory, and there’s a race for scientific understanding to catch up to where we’ve gotten via the pure scaling of neural nets and the compute and data used to train them. In quantum computing, it’s just the opposite: there’s right now a race for practice to catch up to where theory has been since the mid-1990s.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

What Do Our Genes Reveal About Our Past? Richard Dawkins Interviewed

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

What Nate Silver’s Haters Tell Us About Climate Risk

Alex Trembath at the Breakthrough Institute:

It’s election season, which means a return to the quadrennial tradition of yelling at Nate Silver on the Internet. While I think most people at this point have made their peace with his probabilistic forecasts, many progressives, demonstrably confused by basic statistics, regularly accuse Silver of deliberately underestimating Democrats’ electoral fortunes. And it occurred to me that their confusion mirrors a similar mistake progressives make in evaluating climate impacts. In each case, many observers fail to understand the ways in which relatively modest changes in statistical averages are associated with larger relative shifts in the tails of the probability distribution. The funny thing is, the misunderstanding runs in opposite directions in the case of climate versus the case of election forecasting.

It’s election season, which means a return to the quadrennial tradition of yelling at Nate Silver on the Internet. While I think most people at this point have made their peace with his probabilistic forecasts, many progressives, demonstrably confused by basic statistics, regularly accuse Silver of deliberately underestimating Democrats’ electoral fortunes. And it occurred to me that their confusion mirrors a similar mistake progressives make in evaluating climate impacts. In each case, many observers fail to understand the ways in which relatively modest changes in statistical averages are associated with larger relative shifts in the tails of the probability distribution. The funny thing is, the misunderstanding runs in opposite directions in the case of climate versus the case of election forecasting.

Start with the politics. Silver has been publishing his election forecasting model for the better part of twenty years, over five different presidential races and thousands of Congressional races. Progressives with less training in statistics have had that entire time to learn the basics of probabilistic forecasting. And many of them have steadfastly refused to do so.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday Poem

The Pathetic Fallacy

—an excerpt

The Saint Meets His Match, The Saint Goes Underground,

Pope’s translation of The Aeneid,

The Collected Trollop, the last five issues of Baseball Digest,

a whole library of French semanticists

piled on the hospital bed,

on the bed table. If he was going to be attached

to machines, tubes running into all kinds of places

on him, he refused to suffer

alone. He brought Sir Philip Sydney for company,

Samuel Daniel, Edmund Waller,

and the entire sixteenth century.

Coleridge shared his bed along with Flannery O’Conner

and John Woolman. If he ever was going to indulge himself,

what better time? Piled on the Bureau:

The Lysistrata, The Inferno (in three translations), Paradise Lost,

and The Life and Death of Buddy Holly,

books heaped so high

it looked as if he was conducting an experiment

to test precisely how long before everything collapses.

by Christopher Bursk

from The Last Inhabitants of Arcadia

University of Arkansas Press, 2006

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

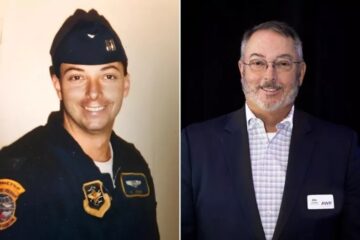

My War Experiences Changed Me. Civilian Life Brought a Hard Realization

Jim Lorraine in Newsweek:

My family has always served in the military. My father was one of six brothers. They all went to World War Two, each in a different service and theater, and all came home. I was around 10 when my brother-in-law was in Vietnam, which was impactful, and my sister was an Air Force nurse. I always wanted to follow their example and serve in the military and was passionate about serving the United States of America as part of something bigger than myself. Originally, I wanted to be a pilot, but I didn’t realize until I went to the military recruiter that I was colorblind, so I didn’t qualify for flight status as a pilot. However, I had gone through nursing school. So, I joined the Air Force as a nurse and was assessed into its aeromedical evacuation program, which is the long-range movement of patients. This program gave me opportunities to fly, see the world, and care for wounded, ill, or injured. After joining, I served around the globe: In Iraq in both Gulf Wars, Somalia during the 1990s, Afghanistan late in the Soviet invasion, demining missions in Vietnam and Cambodia, work in Central America, and the Global War on Terror around the world.

My family has always served in the military. My father was one of six brothers. They all went to World War Two, each in a different service and theater, and all came home. I was around 10 when my brother-in-law was in Vietnam, which was impactful, and my sister was an Air Force nurse. I always wanted to follow their example and serve in the military and was passionate about serving the United States of America as part of something bigger than myself. Originally, I wanted to be a pilot, but I didn’t realize until I went to the military recruiter that I was colorblind, so I didn’t qualify for flight status as a pilot. However, I had gone through nursing school. So, I joined the Air Force as a nurse and was assessed into its aeromedical evacuation program, which is the long-range movement of patients. This program gave me opportunities to fly, see the world, and care for wounded, ill, or injured. After joining, I served around the globe: In Iraq in both Gulf Wars, Somalia during the 1990s, Afghanistan late in the Soviet invasion, demining missions in Vietnam and Cambodia, work in Central America, and the Global War on Terror around the world.

I was around 10 when my brother-in-law was in Vietnam, which was impactful, and my sister was an Air Force nurse. I always wanted to follow their example and serve in the military and was passionate about serving the United States of America as part of something bigger than myself. Originally, I wanted to be a pilot, but I didn’t realize until I went to the military recruiter that I was colorblind, so I didn’t qualify for flight status as a pilot. However, I had gone through nursing school. So, I joined the Air Force as a nurse and was assessed into its aeromedical evacuation program, which is the long-range movement of patients. This program gave me opportunities to fly, see the world, and care for wounded, ill, or injured.

There are countless stories. In the 1980s, I was part of a team that aeromedically evacuated Mujahadeen and their families through Pakistan and Eastern Afghanistan to the United States and European hospitals. During one of many missions, we evacuated Afghan children who were losing arms and eyesight due to candy and toys that the Soviets booby-trapped.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Gaza: Why is it so hard to establish the death toll?

Smriti Mallapaty in Nature:

Since war broke out in the Gaza Strip almost a year ago, the official number of Palestinians killed exceeds 41,000. But this number has stoked controversy. Some researchers think it is an underestimate, owing to the difficulties of trying to count dead people during conflicts. Other sources say it overestimates the number of casualties. The count comes from the Palestinian Ministry of Health — Gaza, the main institution counting mortality in the region. It’s important to track fatalities during wars — and to estimate overall mortality — to hold warring parties accountable and to advocate for the protection of civilians, says Zeina Jamaluddine, an epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. The number of deaths also informs discussions around when to officially declare that a situation involves famine.

Since war broke out in the Gaza Strip almost a year ago, the official number of Palestinians killed exceeds 41,000. But this number has stoked controversy. Some researchers think it is an underestimate, owing to the difficulties of trying to count dead people during conflicts. Other sources say it overestimates the number of casualties. The count comes from the Palestinian Ministry of Health — Gaza, the main institution counting mortality in the region. It’s important to track fatalities during wars — and to estimate overall mortality — to hold warring parties accountable and to advocate for the protection of civilians, says Zeina Jamaluddine, an epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. The number of deaths also informs discussions around when to officially declare that a situation involves famine.

In the heat of conflict, the first way to count fatalities is to tally up the number of dead people. But capturing the number of deaths in the densely populated urban centres of Gaza presents unique challenges, says Emily Tripp, director of Airwars, a non-profit watchdog based in London that counts casualties in times of conflict. “What we’ve seen in Gaza is entire families just being completely wiped out,” says Tripp. That means it can be hard to recover bodies, or there is no one to report them dead, and so deceased people will be missed in counts. Only when the conflict ends or eases can researchers begin the work of getting more robust estimates of overall mortality through surveys, modelling and statistical tools, they say.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Monday, September 23, 2024

Can liberal virtue rescue liberal justice?

George Scialabba in Commonweal:

All men are brothers.” (Women too, of course.) If asked to agree or disagree with this statement, taken in a normative sense, most people would agree. At the moment, Ukrainians might make an exception for Russians, and Israelis and Palestinians for one another—though even they, if they listened to the better angels of their nature, might come around.

All men are brothers.” (Women too, of course.) If asked to agree or disagree with this statement, taken in a normative sense, most people would agree. At the moment, Ukrainians might make an exception for Russians, and Israelis and Palestinians for one another—though even they, if they listened to the better angels of their nature, might come around.

Why quote this old saw here? Because I have long felt that these four words are a complete and adequate political philosophy. A brother or sister shares most of one’s genes and usually a good many of one’s early formative experiences. It’s a tie that binds. Of course, most people are not literally our brothers or sisters. But the point of that archaic-sounding phrase “the brotherhood of man” is to jog our moral imaginations, to remind us that even if we don’t share parents with most other humans, we share with all of them something even more important, something that binds us to them even more strongly: a capacity for suffering. Remembering that makes it harder to be indifferent or cruel.

The most influential move in modern political philosophy is just such an appeal to our imaginations. In A Theory of Justice (1971), John Rawls, having defined fairness as the chief virtue of liberal societies, asks how we might all agree on what’s fair.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How AI ‘Embeddings’ Encode What Words Mean — Sort Of

John Pavlus in Quanta:

A picture may be worth a thousand words, but how many numbers is a word worth? The question may sound silly, but it happens to be the foundation that underlies large language models, or LLMs — and through them, many modern applications of artificial intelligence.

A picture may be worth a thousand words, but how many numbers is a word worth? The question may sound silly, but it happens to be the foundation that underlies large language models, or LLMs — and through them, many modern applications of artificial intelligence.

Every LLM has its own answer. In Meta’s open-source Llama 3 model, each word contains 4,096 numbers; for GPT-3, it’s 12,288. Individually, these long numerical lists — known as embeddings — are just inscrutable chains of digits. But in concert, they encode mathematical relationships between words that can look surprisingly like meaning.

The basic idea behind word embeddings is decades old. To model language on a computer, start by taking every word in the dictionary and making a list of its essential features — how many is up to you, as long as it’s the same for every word. “You can almost think of it like a 20 Questions game,” said Ellie Pavlick, a computer scientist studying language models at Brown University and Google DeepMind. “Animal, vegetable, object — the features can be anything that people think are useful for distinguishing concepts.” Then assign a numerical value to each feature in the list. The word “dog,” for example, would score high on “furry” but low on “metallic.” The result will embed each word’s semantic associations, and its relationship to other words, into a unique string of numbers.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.