Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

John Amos (1939 – 2024) Actor

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday, October 4, 2024

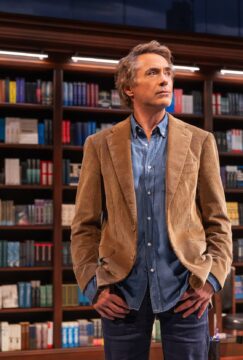

On Ayad Akhtar’s new play “McNeal”

Amitava Kumar at his Substack:

“McNeal,” Ayad Akhtar’s play that just opened at Lincoln Center, stars Robert Downey Jr. in the role of a novelist named Jacob McNeal.

The set is bathed in the soft blue glow of an iPhone screen. In fact, when the play starts in the dark, the backdrop is a phone screen on which with the tapping sounds of an iPhone keyboard we see the moving cursor form the following question: “Who will win the Nobel Prize in Literature this year?”

The GPT responds: “The selection process for the Nobel is highly secretive…. As an AI language model, I cannot accurately predict the recipient of the Nobel Prize or any other future event. I’m sorry.”

The person typing these words is, of course, the play’s protagonist himself. A prominent novelist in his sixties, Jacob McNeal. He is about to arrive at his doctor’s where he is being treated for Stage 3 liver disease. He has gone back to drinking because the month of October, when the Nobel is announced, is a tough month for him. He’s in serious trouble, the doctor says; the AI model called Suarez that tracks liver function has McNeal ending with liver failure within three months.

I must pause here and note a couple of things.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How to win a Nobel prize

Kerri Smith & Chris Ryan in Nature:

The Nobel prize has been awarded in three scientific fields — chemistry, physics and physiology or medicine — almost every year since 1901, barring some disruptions mostly due to wars.

The Nobel prize has been awarded in three scientific fields — chemistry, physics and physiology or medicine — almost every year since 1901, barring some disruptions mostly due to wars.

Nature crunched the data on the 346 prizes and their 646 winners (Nobel prizes can be shared by up to three people) to work out which characteristics can be reliably linked to medals.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sabine Hossenfelder: Who Will Win This Year’s Nobel Prize in Physics?

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Worst Magazine In America

Nathan J. Robinson in Current Affairs:

Regular Current Affairs readers know that I have a tendency to make grumbling remarks about a magazine called The Atlantic. In fact, in our print edition we recently awarded The Atlantic a prize for “Worst Magazine In America.” This prompted an irate letter from one of our subscribers, who said that they enjoyed The Atlantic very much, and they could not understand our virulent distaste. The reader asked, fairly, if we could explain exactly why we think The Atlantic is such a “bad” magazine. Is it simply because we don’t share its political leanings? Are we mad at The Atlantic for not being socialist? If so, why does it get singled out for special criticism, given that most publications aren’t socialist (including Field & Stream, Good Housekeeping, etc.)? The reader offered an example of an Atlantic article that they thought was quite good: George Packer’s “The Four Americas.” Did we disagree with it, they wondered? If so, why?

Regular Current Affairs readers know that I have a tendency to make grumbling remarks about a magazine called The Atlantic. In fact, in our print edition we recently awarded The Atlantic a prize for “Worst Magazine In America.” This prompted an irate letter from one of our subscribers, who said that they enjoyed The Atlantic very much, and they could not understand our virulent distaste. The reader asked, fairly, if we could explain exactly why we think The Atlantic is such a “bad” magazine. Is it simply because we don’t share its political leanings? Are we mad at The Atlantic for not being socialist? If so, why does it get singled out for special criticism, given that most publications aren’t socialist (including Field & Stream, Good Housekeeping, etc.)? The reader offered an example of an Atlantic article that they thought was quite good: George Packer’s “The Four Americas.” Did we disagree with it, they wondered? If so, why?

I agree with the reader’s point: I shouldn’t just sit around snarkily making cracks about The Atlantic without justifying the position.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

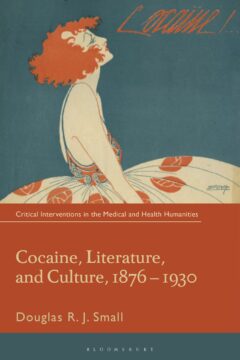

Cocaine: A Cultural History

Douglas Small at Aeon Magazine:

In the winter of 1886, William Alexander Hammond – a famed neurologist and the former Surgeon General of the United States Army – took an enormous amount of cocaine. A reporter from the New York paper The Sun who interviewed him waggishly observed that the doctor had been ‘on a terrific spree for science’. Hammond had experimentally worked his way through as many different ways of taking the drug in as many different quantities as he could devise: he tried fluid extracts of coca (the plant from which pure cocaine is extracted), mixed grains of cocaine hydrochloride into purified wines, and eventually began injecting the drug hypodermically. The injections, he said, gave him ‘a delightful, undulating thrill’. On cocaine, everything felt ‘refined’ and ‘softened’. Hammond became intensely talkative: when he was alone, he would talk to himself at great length. ‘I became,’ he said, ‘rather sentimental and said nice things to everybody. The world was going very well, and I had a favourable opinion of my fellow men and women … I enjoyed myself hugely.’

In the winter of 1886, William Alexander Hammond – a famed neurologist and the former Surgeon General of the United States Army – took an enormous amount of cocaine. A reporter from the New York paper The Sun who interviewed him waggishly observed that the doctor had been ‘on a terrific spree for science’. Hammond had experimentally worked his way through as many different ways of taking the drug in as many different quantities as he could devise: he tried fluid extracts of coca (the plant from which pure cocaine is extracted), mixed grains of cocaine hydrochloride into purified wines, and eventually began injecting the drug hypodermically. The injections, he said, gave him ‘a delightful, undulating thrill’. On cocaine, everything felt ‘refined’ and ‘softened’. Hammond became intensely talkative: when he was alone, he would talk to himself at great length. ‘I became,’ he said, ‘rather sentimental and said nice things to everybody. The world was going very well, and I had a favourable opinion of my fellow men and women … I enjoyed myself hugely.’

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday Poem

Silver Maple, Solstice

And still, forty years later, I lean

my cheek to your trunk, breathe

familiar summer. I imagine the sap

pulse running through, what your roots

tell the lake, what they told the other

two other maples you once knew,

network of under earth shared

in the black of Michigan soil. Storms

stole them, trunks yanked back

from decades. Lightning severed,

both fell with such protest they took

a house right down to its stone

basement heart. They never wanted to go.

I share this with them. I share

this with you. Keep up in gale and ice,

hundreds high. Hold fast in spring’s

torment wind. Abandon any blight.

Attend only to the insects

that adore, the birds that make

respectful nests. I say this all as I round

you, touch a secret I don’t want to admit:

one small rusted nail. You’ve grown

around it, taken the scar as a mossed beauty.

But I remember the story another way:

the tin sign it held after we hammered

it into you: Payne Cottage, est. 1982.

Forgive us for wanting to claim

what was never grown for owning.

Forgive us for attempting to harness majesty,

believing it was anything but yours.

by Julie Bloemeke

from Echotheo Review

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

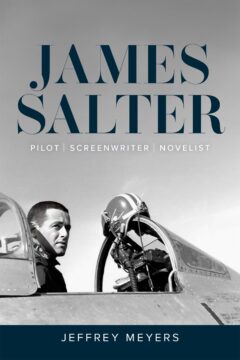

James Salter: Pilot, Screenwriter, Novelist

Tom Lamont at Literary Review:

In the last days of the 1960s, James Salter, a pilot who had left the US Air Force to try to make it as a writer, was living in Aspen, subsisting on piecemeal writing gigs: screenplays, stories, essays, profiles. As a celebrity interviewer for People, he was humiliated by two famous men of letters, Graham Greene and Vladimir Nabokov, as he attempted to meet them. By this time, Salter had published three novels himself: two of them drew on his experiences in the military, while the other, A Sport and a Pastime, recounted an affair in provincial France. At the end of 1969, he received a letter from a stranger, Robert Phelps, a critic and editor based in New York, who called A Sport and a Pastime his favourite novel of the decade. ‘I must make you some sort of sign,’ Phelps wrote.

As Jeffrey Meyers tells us in his thorough, always interesting, occasionally idiosyncratic study of Salter’s life and career – the first to be published since his death in 2015 – that initial contact gave Salter great pleasure, arriving at a time when he was in need of affirmation. His marriage was rocky. He had abandoned a safe career in favour of one that was patchy and badly paid.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Carl Phillips’s Latest Poems

Nick Ripatrazone at Poetry Magazine:

In 1999, nearly a decade after he first devoted himself to poetry, Phillips drove through a blizzard to interview the poet Geoffrey Hill. The esteemed, Oxford-educated, English poet had been Phillips’s teacher at Boston University. When In the Blood was published, Phillips left his teaching position and returned to Harvard to pursue a doctorate in classical philology. His second time there was brief. Deciding instead to study poetry with Robert Pinsky, Phillips entered the single-year MA program at Boston University.

In 1999, nearly a decade after he first devoted himself to poetry, Phillips drove through a blizzard to interview the poet Geoffrey Hill. The esteemed, Oxford-educated, English poet had been Phillips’s teacher at Boston University. When In the Blood was published, Phillips left his teaching position and returned to Harvard to pursue a doctorate in classical philology. His second time there was brief. Deciding instead to study poetry with Robert Pinsky, Phillips entered the single-year MA program at Boston University.

There, Phillips enrolled in Hill’s “The Poetry of Religion” course, where he first read George Herbert, John Donne, and two Jesuit priests: Robert Southwell and Gerard Manley Hopkins. Hill revered the Elizabethan Jesuits. When he offered a seminar on Hopkins the next semester, Phillips enrolled. He only had one other classmate.

Hill was a “formidable” teacher, Phillips recalled. The three-hour classes included “having to recite memorized Hopkins poems to [Hill], being loudly corrected at each mispronunciation.”

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

James Salter Reads From “Burning the Days.”

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Life of a Poet: Carl Phillips

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

I Quit Teaching Because of ChatGPT

Victoria Livingstone in Time Magazine:

This fall is the first in nearly 20 years that I am not returning to the classroom. For most of my career, I taught writing, literature, and language, primarily to university students. I quit, in large part, because of large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT.

This fall is the first in nearly 20 years that I am not returning to the classroom. For most of my career, I taught writing, literature, and language, primarily to university students. I quit, in large part, because of large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT.

Virtually all experienced scholars know that writing, as historian Lynn Hunt has argued, is “not the transcription of thoughts already consciously present in [the writer’s] mind.” Rather, writing is a process closely tied to thinking. In graduate school, I spent months trying to fit pieces of my dissertation together in my mind and eventually found I could solve the puzzle only through writing. Writing is hard work. It is sometimes frightening. With the easy temptation of AI, many—possibly most—of my students were no longer willing to push through discomfort.

Three Iconic Directors: Gurinder Chadha, Deepa Mehta, and Mira Nair

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Should A Philosopher Have Sayings?

Nandi Theunissen at The Point:

Academic philosophers—people for whom philosophy is a profession—like to joke about their discomfort on airplanes. As you make light conversation with your neighbor, the question of what you do for a living tends to come up, and then you have to cope with other people’s ideas about what it is to “do philosophy.” A friend from graduate school confessed that he hated these conversations so much he would pretend to be a mathematician. (Why not a financial adviser or a travel agent?) A colleague from my first job at Johns Hopkins would head things off by saying “I teach philosophy” rather than “I am a philosopher.” It definitely sounds more approachable. But when I still felt the novelty of being a professional philosopher—and pride at having survived the rigors of graduate school—I was not about to dumb it down. I was even eager to tell people I was a philosopher. Follow-up questions fell within a range: Who are your favorite philosophers? Does anyone listen to you? Isn’t that a job from the olden days?

Academic philosophers—people for whom philosophy is a profession—like to joke about their discomfort on airplanes. As you make light conversation with your neighbor, the question of what you do for a living tends to come up, and then you have to cope with other people’s ideas about what it is to “do philosophy.” A friend from graduate school confessed that he hated these conversations so much he would pretend to be a mathematician. (Why not a financial adviser or a travel agent?) A colleague from my first job at Johns Hopkins would head things off by saying “I teach philosophy” rather than “I am a philosopher.” It definitely sounds more approachable. But when I still felt the novelty of being a professional philosopher—and pride at having survived the rigors of graduate school—I was not about to dumb it down. I was even eager to tell people I was a philosopher. Follow-up questions fell within a range: Who are your favorite philosophers? Does anyone listen to you? Isn’t that a job from the olden days?

Then on a flight from New York to Los Angeles I was asked, What are your philosophical sayings?

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday, October 3, 2024

The Italian Art Of Violence

Samm Deighan at The Current:

An ominous figure with an obscured face, clad in a trench coat, fedora, and leather gloves—all black—stalks a young model through a gloomy antique shop packed with statues, lamps, and ornate furniture. Though the store is in near darkness, pink and teal lights flash inexplicably in the background. Dramatically canted camera angles emphasize the model’s growing panic and confusion as she crashes around in the dark, desperate to escape. But the killer sneaks up on her, just as she reaches an exit door, and smashes a cruelly hooked gauntlet from a nearby suit of armor into her face, instantly killing her.

An ominous figure with an obscured face, clad in a trench coat, fedora, and leather gloves—all black—stalks a young model through a gloomy antique shop packed with statues, lamps, and ornate furniture. Though the store is in near darkness, pink and teal lights flash inexplicably in the background. Dramatically canted camera angles emphasize the model’s growing panic and confusion as she crashes around in the dark, desperate to escape. But the killer sneaks up on her, just as she reaches an exit door, and smashes a cruelly hooked gauntlet from a nearby suit of armor into her face, instantly killing her.

This sequence from Mario Bava’s Blood and Black Lace (1964), generally regarded as the first giallo film, set the template for a type of highly stylized, lavishly decorated murder set piece that would be replicated in hundreds of Italian horror movies to follow throughout the 1970s and early ’80s. Bava established many of the subgenre’s visual and thematic tropes, while helping cement the giallo plot formula as a perverse, violent variation on the classic murder mystery.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

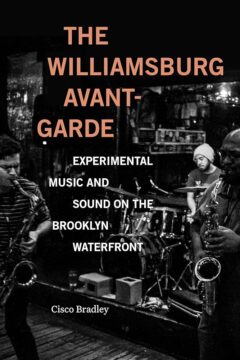

The Williamsburg Avant-Garde

Brendan Riley at the LARB:

CISCO BRADLEY’S The Williamsburg Avant-Garde: Experimental Music and Sound on the Brooklyn Waterfront (2023) chronicles a vital and now-vanished facet of American musical and cultural history in New York City from the mid-1980s to 2015. The book investigates how, amid hypercommercialism and mutating audio technologies, bold musicians, expert and amateur alike, impelled by a big-hearted DIY ethos, made new, imaginative music as public, independent, and free as possible by exploiting urban niches and cultural interstices, using dive bars, loft spaces, garages, warehouses, restaurants, and cafés as musical laboratories for experiments in sound, installation, and performance.

CISCO BRADLEY’S The Williamsburg Avant-Garde: Experimental Music and Sound on the Brooklyn Waterfront (2023) chronicles a vital and now-vanished facet of American musical and cultural history in New York City from the mid-1980s to 2015. The book investigates how, amid hypercommercialism and mutating audio technologies, bold musicians, expert and amateur alike, impelled by a big-hearted DIY ethos, made new, imaginative music as public, independent, and free as possible by exploiting urban niches and cultural interstices, using dive bars, loft spaces, garages, warehouses, restaurants, and cafés as musical laboratories for experiments in sound, installation, and performance.

A densely layered, kaleidoscopic musicological treatise, Williamsburg draws on hundreds of interviews, articles, essays, and recordings to describe the historical impact of a daunting array of musicians, ensembles, musical genres, stylistic innovations, and movements, and the Northern Brooklyn locales that fostered them. It was a singular era propelled by a relentless quest for the new and different—and by musicians’ struggles to survive the vicissitudes of the marketplace.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Butch Morris Demonstrates “Conduction”

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

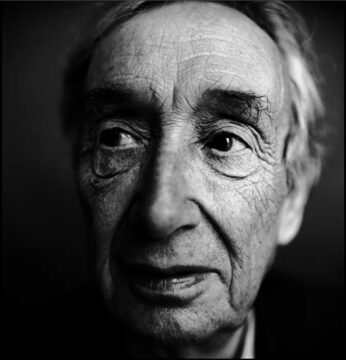

What The Photographer Who’s Taken Hundreds Of Philosopher Portraits Really Thinks Of Philosophers

Alex King at Aesthetics for Birds:

AK: Let’s start off where your story with philosophers begins. Could you tell me a bit about the original “Philosophers” series?

SP: I’ve made two series of portraits of philosophers. The first series was during the late ’80s and ’90s and contained about eighty people, and the second continued through the ’90s until 2008 and contained a hundred more.

The first series came about after Sir A.J. Ayer suggested I do it. The series had a big impact because it outed what philosophers actually looked like. Remember, when I photographed the philosophers the first time around, there was no internet. There was no way of knowing what a philosopher looked like unless they were pictured on a book jacket. I think Quine had a picture that was photographed in the forties! They were not that image-conscious a bunch. Not then.

I met the most amazing people—people like Jack Rawls and David Lewis. When I met Freddie Ayer, he was an 88- or 90-year-old man. He was very much seen as the face of philosophy after Bertrand Russell.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

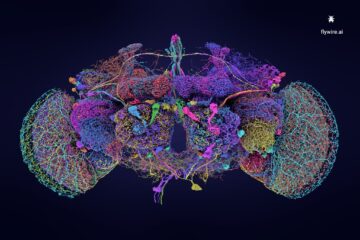

Scientists have mapped out how 140,000 neurons are wired in the brain of the fruit fly

Carl Zimmer in the New York Times:

A fruit fly’s brain is smaller than a poppy seed, but it packs tremendous complexity into that tiny space. Over 140,000 neurons are joined together by more than 490 feet of wiring, as long as four blue whales placed end to end.

A fruit fly’s brain is smaller than a poppy seed, but it packs tremendous complexity into that tiny space. Over 140,000 neurons are joined together by more than 490 feet of wiring, as long as four blue whales placed end to end.

Hundreds of scientists mapped out those connections in stunning detail in a series of papers published on Wednesday in the journal Nature. The wiring diagram will be a boon to researchers who have studied the nervous system of the fly species, Drosophila melanogaster, for generations.

Previously, a tiny worm was the only adult animal to have had its brain entirely reconstructed, with just 385 neurons in its entire nervous system. The new fly map is “the first time we’ve had a complete map of any complex brain,” said Mala Murthy, a neurobiologist at Princeton who helped lead the effort.

Other researchers said that analyzing the circuitry in the fly brain would reveal principles that apply to other species, including humans, whose brains have 86 billion neurons.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.