Max Krupnick in Harvard Magazine:

With one minute left in Harvard’s last men’s basketball game of the 2023-2024 season, sophomore Chisom Okpara drove toward the basket, leaped, and released the ball. It clanked off the rim back into his hands. On the second attempt, he made the shot, his twenty-fifth point of the game. He did not know that would be his final Crimson bucket.

With one minute left in Harvard’s last men’s basketball game of the 2023-2024 season, sophomore Chisom Okpara drove toward the basket, leaped, and released the ball. It clanked off the rim back into his hands. On the second attempt, he made the shot, his twenty-fifth point of the game. He did not know that would be his final Crimson bucket.

Okpara was happy with his team, academics, and social life. But in April, star first-year point guard Malik Mack entered the transfer portal, which allowed coaches from other schools to recruit him. Soon after, fellow Ivy League sophomores Danny Wolf (Yale) and Kalu Anya (Brown) followed suit. Anya, a childhood friend, counseled Okpara to “just enter your name,” Okpara recalls. “You don’t know what’s going to happen. You can always come back.” Once Okpara entered the transfer portal, schools ranging from Auburn and Texas to Stanford and Vanderbilt pursued him. These schools, he said, told him he could make between $200,000 and $500,000 by playing for their basketball team. On May 22, he committed to Stanford, where he will play against stronger competitors while earning a significant amount of money.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

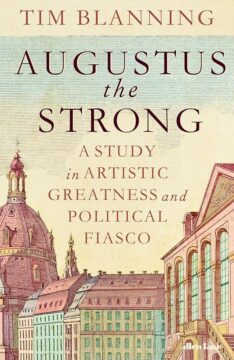

Unsuccessful in politics and war, Augustus turned to culture. He transformed Dresden into a city which, even after the notorious bombing raid of February 1945, is still handsome. The highlights include the Zwinger, a palace complex that served as a setting for festivities, the Frauenkirche and the 437-metre-long Augustus Bridge, which linked the centre with the New Town on the other side of the Elbe, helping to create an integrated urban landscape. Next door to the Zwinger, Augustus built the largest opera house in Germany. Blanning enthuses about his success in attracting architects, artists and musicians to Saxony, the most famous being Johann Sebastian Bach, who arrived in Leipzig, Saxony’s other main city, in 1723.

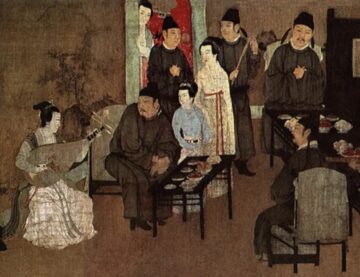

Unsuccessful in politics and war, Augustus turned to culture. He transformed Dresden into a city which, even after the notorious bombing raid of February 1945, is still handsome. The highlights include the Zwinger, a palace complex that served as a setting for festivities, the Frauenkirche and the 437-metre-long Augustus Bridge, which linked the centre with the New Town on the other side of the Elbe, helping to create an integrated urban landscape. Next door to the Zwinger, Augustus built the largest opera house in Germany. Blanning enthuses about his success in attracting architects, artists and musicians to Saxony, the most famous being Johann Sebastian Bach, who arrived in Leipzig, Saxony’s other main city, in 1723. A painting is not something we step into. We might crave a landscape, a room, a street, a scene or a background, but we can’t inhabit the painter’s vision of it. Our eyes inch closer as they focus on areas of the work, but the view stops there: We remain outsiders, left out in the cold.

A painting is not something we step into. We might crave a landscape, a room, a street, a scene or a background, but we can’t inhabit the painter’s vision of it. Our eyes inch closer as they focus on areas of the work, but the view stops there: We remain outsiders, left out in the cold. I think and talk a lot about the risks of powerful AI. The company I’m the CEO of, Anthropic, does a lot of research on how to reduce these risks. Because of this, people sometimes draw the conclusion that I’m a pessimist or “doomer” who thinks AI will be mostly bad or dangerous. I don’t think that at all. In fact, one of my main reasons for focusing on risks is that they’re the only thing standing between us and what I see as a fundamentally positive future. I think that most people are underestimating just how radical the upside of AI could be, just as I think most people are underestimating how bad the risks could be.

I think and talk a lot about the risks of powerful AI. The company I’m the CEO of, Anthropic, does a lot of research on how to reduce these risks. Because of this, people sometimes draw the conclusion that I’m a pessimist or “doomer” who thinks AI will be mostly bad or dangerous. I don’t think that at all. In fact, one of my main reasons for focusing on risks is that they’re the only thing standing between us and what I see as a fundamentally positive future. I think that most people are underestimating just how radical the upside of AI could be, just as I think most people are underestimating how bad the risks could be. Alongside equality, freedom and opportunity, fear has long played a powerful role in political discourse. In ordinary life, fear is often a fitting response to danger. If you encounter a snake while out on a hike, fear will lead you to back away and exercise caution. If the snake is poisonous, fear will have saved your life. By contrast, the fears that dominate political discourse are less concrete. We are told to fear elites, terrorists, religious zealots, godless atheists, sexists, feminists, Marxists and the enemies of democracy. Yet even as these purported poisons are less obviously lethal, political rhetoricians have long understood that making them salient is a powerful way to shape citizens’ motivations. As Donald Trump told Bob Woodward: real power is fear.

Alongside equality, freedom and opportunity, fear has long played a powerful role in political discourse. In ordinary life, fear is often a fitting response to danger. If you encounter a snake while out on a hike, fear will lead you to back away and exercise caution. If the snake is poisonous, fear will have saved your life. By contrast, the fears that dominate political discourse are less concrete. We are told to fear elites, terrorists, religious zealots, godless atheists, sexists, feminists, Marxists and the enemies of democracy. Yet even as these purported poisons are less obviously lethal, political rhetoricians have long understood that making them salient is a powerful way to shape citizens’ motivations. As Donald Trump told Bob Woodward: real power is fear. Around 2,500 years ago, Babylonian traders in Mesopotamia impressed two slanted wedges into clay tablets. The shapes represented a placeholder digit, squeezed between others, to distinguish numbers such as 50, 505 and 5,005. An elementary version of the concept of zero was born.

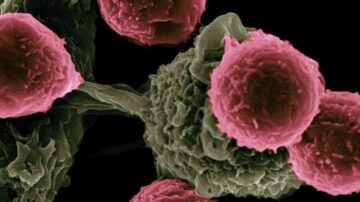

Around 2,500 years ago, Babylonian traders in Mesopotamia impressed two slanted wedges into clay tablets. The shapes represented a placeholder digit, squeezed between others, to distinguish numbers such as 50, 505 and 5,005. An elementary version of the concept of zero was born. For the first time, an off-the-shelf CAR T cell therapy has been used to treat potentially life-threatening autoimmune disorders in three people. With a single shot,

For the first time, an off-the-shelf CAR T cell therapy has been used to treat potentially life-threatening autoimmune disorders in three people. With a single shot,  Across 15,000 generations, human beings have looked out at the sentinel stars and felt the pressing weight of myriad existential questions: Are we alone? Are there other planets also orbiting distant suns? If so, have any of these other worlds also birthed life, or is the drama of our Earth a singular cosmic accident? And what about other minds and civilizations? Have others in the universe, through their success as tool-builders and world-makers, also brought themselves to the brink of collapse?

Across 15,000 generations, human beings have looked out at the sentinel stars and felt the pressing weight of myriad existential questions: Are we alone? Are there other planets also orbiting distant suns? If so, have any of these other worlds also birthed life, or is the drama of our Earth a singular cosmic accident? And what about other minds and civilizations? Have others in the universe, through their success as tool-builders and world-makers, also brought themselves to the brink of collapse? In Amrith’s view, all history is environmental history. And that includes both environmental effects on societies and those societies’ impacts on the environment. He cites evidence, for example, suggesting that a “medieval warm period” spanned most of Europe and parts of North America and western Asia through the 13th century. The period’s benign climate and rainfall, he argues, allowed societies to clear land, expand cultivation, build cities, and grow their populations. He also assesses the rise and fall of the Mongols, who swept across Asia quickly before being thwarted by limited grasses for their horses, intense snowstorms and earthquakes, and deadly plagues that the Mongolian expansion helped spread.

In Amrith’s view, all history is environmental history. And that includes both environmental effects on societies and those societies’ impacts on the environment. He cites evidence, for example, suggesting that a “medieval warm period” spanned most of Europe and parts of North America and western Asia through the 13th century. The period’s benign climate and rainfall, he argues, allowed societies to clear land, expand cultivation, build cities, and grow their populations. He also assesses the rise and fall of the Mongols, who swept across Asia quickly before being thwarted by limited grasses for their horses, intense snowstorms and earthquakes, and deadly plagues that the Mongolian expansion helped spread.