Jeffrey Kluger in Time Magazine:

Sleep is a moving target. When you were a newborn, you slept for most of the day, then less as an older child; as a teen, you slept later. A senior’s bedtime is earlier—part of a lifetime journey of rising and falling sleep needs depending on age. How much sleep do you need at the various stages of life, and why do our requirements shift all the time?

Sleep is a moving target. When you were a newborn, you slept for most of the day, then less as an older child; as a teen, you slept later. A senior’s bedtime is earlier—part of a lifetime journey of rising and falling sleep needs depending on age. How much sleep do you need at the various stages of life, and why do our requirements shift all the time?

Babies aged zero to three months sleep 14 to 17 hours out of every 24—partly a function of the newborn’s introduction to the world after three trimesters in the darkness of the womb. A large share of time in the womb is spent sleeping, and the reason for so much slumber is the same both before and after birth: growth. Babies triple their weight between birth and one year old, and it’s during sleep—especially the deep cycle called slow-wave sleep—that growth hormone is most prodigiously released. Adding bulk is not the only thing the youngest babies are doing.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

What is a novel, or any work of art, but the product of its time, of commerce? What is it but another colorful consumer unit, to be slid dutifully on a shelf or hawked through the internet? I’ve been mulling, of late, actions and reactions, the trope of the lone genius and the trope of systems. One held very long in the culture before being defenestrated, in academia at least, over the last several decades. The other is now dominant—at least, among those in the know, those who still analyze literature. In a systems conception, the genius of creation is disregarded and dismissed; no lone spark could truly emerge, no individual could labor, by herself, to write the novels, poems, or plays that endure across the ages, or even get remembered a decade after publication. Christian Lorentzen’s

What is a novel, or any work of art, but the product of its time, of commerce? What is it but another colorful consumer unit, to be slid dutifully on a shelf or hawked through the internet? I’ve been mulling, of late, actions and reactions, the trope of the lone genius and the trope of systems. One held very long in the culture before being defenestrated, in academia at least, over the last several decades. The other is now dominant—at least, among those in the know, those who still analyze literature. In a systems conception, the genius of creation is disregarded and dismissed; no lone spark could truly emerge, no individual could labor, by herself, to write the novels, poems, or plays that endure across the ages, or even get remembered a decade after publication. Christian Lorentzen’s  But I’d like to turn, at least at the outset, to a consideration of the sheer artistry of Morrison’s film, how even though its pacing is entirely dictated by the inevitable facticity and specificity of the tick-tock of the film’s method (all Morrison has done is to expertly align the time-signatures of a wide array of simultaneously running cameras and then cut in and out amongst them, guiding the viewer’s attention across a shifting grid of all that simultaneity), it is still remarkable how many editorially flecked or at any rate consciously discerned and foregrounded themes nevertheless emerge.

But I’d like to turn, at least at the outset, to a consideration of the sheer artistry of Morrison’s film, how even though its pacing is entirely dictated by the inevitable facticity and specificity of the tick-tock of the film’s method (all Morrison has done is to expertly align the time-signatures of a wide array of simultaneously running cameras and then cut in and out amongst them, guiding the viewer’s attention across a shifting grid of all that simultaneity), it is still remarkable how many editorially flecked or at any rate consciously discerned and foregrounded themes nevertheless emerge.  On its surface, the book is deceptively simple. At first hating Svalbard and seeing only bleak desolation, she undergoes a change, learning a great deal about herself, humanity, and the wild in the process. This is a cliched appraisal of the book, but part of its charm is how clearly these beats are telegraphed, and how skillfully she delivers on what you already suspect is coming.

On its surface, the book is deceptively simple. At first hating Svalbard and seeing only bleak desolation, she undergoes a change, learning a great deal about herself, humanity, and the wild in the process. This is a cliched appraisal of the book, but part of its charm is how clearly these beats are telegraphed, and how skillfully she delivers on what you already suspect is coming. The same week this new two-volume edition of Charles Baudelaire’s Œuvres complètes arrived in bookshops, Spotify unveiled a new advert in the Paris Métro. It read: “You knew Le Spleen de Paris, here’s the Spleen of La Courneuve”. In the heart of the Seine-Saint-Denis banlieue, La Courneuve is a few miles north of the centre of Paris, where Baudelaire was born and mostly raised. On the other side of the périphérique ring road, it is where Jules Jomby’s family moved from Cameroon when he was six. Jules grew up in the blocks of council flats called the Cité des 4000, famously profiled in Jean-Luc Godard’s Deux ou trois choses que je sais d’elle (1967). Later, Jules was to adopt the stage name Dinos as he launched a successful rap career; later still, he was to draw inspiration from Baudelaire on his track “Spleen”, from his first studio album, Imany (2018).

The same week this new two-volume edition of Charles Baudelaire’s Œuvres complètes arrived in bookshops, Spotify unveiled a new advert in the Paris Métro. It read: “You knew Le Spleen de Paris, here’s the Spleen of La Courneuve”. In the heart of the Seine-Saint-Denis banlieue, La Courneuve is a few miles north of the centre of Paris, where Baudelaire was born and mostly raised. On the other side of the périphérique ring road, it is where Jules Jomby’s family moved from Cameroon when he was six. Jules grew up in the blocks of council flats called the Cité des 4000, famously profiled in Jean-Luc Godard’s Deux ou trois choses que je sais d’elle (1967). Later, Jules was to adopt the stage name Dinos as he launched a successful rap career; later still, he was to draw inspiration from Baudelaire on his track “Spleen”, from his first studio album, Imany (2018). From its inception, pop (and rock) music was about youth. It offered a sound and a culture that stood in direct contrast, if not opposition, to the smugness of America’s Greatest Generation and to the choking conformity of postwar austerity Britain. It was made by the young, for the young. It was supposed to be ephemeral, disposable, temporary. The consumers would grow tired of the dance and move on to more adult, societally useful pursuits; the performers would have their moment in the spotlight, then develop jowls and get proper jobs.

From its inception, pop (and rock) music was about youth. It offered a sound and a culture that stood in direct contrast, if not opposition, to the smugness of America’s Greatest Generation and to the choking conformity of postwar austerity Britain. It was made by the young, for the young. It was supposed to be ephemeral, disposable, temporary. The consumers would grow tired of the dance and move on to more adult, societally useful pursuits; the performers would have their moment in the spotlight, then develop jowls and get proper jobs. We’re talking the day after the general election. How do you feel about Labour winning power?

We’re talking the day after the general election. How do you feel about Labour winning power? I

I The rape and killing of a 31-year-old woman medical resident has touched off protests across India as the country grapples with inadequate protections for women and increasing

The rape and killing of a 31-year-old woman medical resident has touched off protests across India as the country grapples with inadequate protections for women and increasing  A

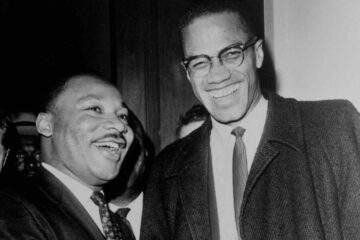

A  The Civil Rights Act of 1964 turns 60 on Tuesday. Its birthday is important because it is a living piece of legislation and a predecessor for laws impacting women’s and LGBTQ+ rights. I can’t help but think about this momentous act and its unifying power and be reminded of the time it brought together two of the greatest men of their generation – Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X.

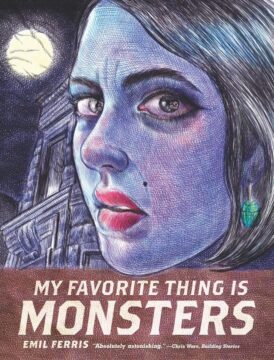

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 turns 60 on Tuesday. Its birthday is important because it is a living piece of legislation and a predecessor for laws impacting women’s and LGBTQ+ rights. I can’t help but think about this momentous act and its unifying power and be reminded of the time it brought together two of the greatest men of their generation – Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. THIS IS A GOTHIC TALE. In the summer of 2002, a professional illustrator and single mom in Chicago went to her fortieth-birthday bash, a gypsy-themed affair that her young daughter told her not to attend. A premonition? At the party, a mosquito bit her. Perhaps she slapped it dead; maybe it stayed attached, vampirically feasting. The result was no mere itch, but a health spiral. She had contracted West Nile disease, in a city very far from either side of that river, plus meningitis and encephalitis, paralyzing her lower body. Her drawing hand no longer worked: her livelihood was at stake. She moved in with her mother, whose dining room could accommodate her hospital bed and wheelchair, and enrolled in the fiction writing program at the Art Institute of Chicago. There were stories she wanted to tell. Maybe she’d revisit an abandoned screenplay from the ’90s, about “a werewolf lesbian girl being enfolded in the protective arms of a Frankenstein trans kid.”

THIS IS A GOTHIC TALE. In the summer of 2002, a professional illustrator and single mom in Chicago went to her fortieth-birthday bash, a gypsy-themed affair that her young daughter told her not to attend. A premonition? At the party, a mosquito bit her. Perhaps she slapped it dead; maybe it stayed attached, vampirically feasting. The result was no mere itch, but a health spiral. She had contracted West Nile disease, in a city very far from either side of that river, plus meningitis and encephalitis, paralyzing her lower body. Her drawing hand no longer worked: her livelihood was at stake. She moved in with her mother, whose dining room could accommodate her hospital bed and wheelchair, and enrolled in the fiction writing program at the Art Institute of Chicago. There were stories she wanted to tell. Maybe she’d revisit an abandoned screenplay from the ’90s, about “a werewolf lesbian girl being enfolded in the protective arms of a Frankenstein trans kid.” MARRIAGE IS A GRIM BUSINESS—worse still if you’re a woman in a Rachel Cusk book. The blame lies with Christian iconography, she writes in her 2012 memoir, Aftermath, and pictures of the “holy family, that pious unit that sucked the world’s attention dry.” There, we found Mary and the manger, the Christ child, cuckolded Joseph: images gathered in a “cult of sentimentality and surfaces” to obscure the innate beastliness of human existence and so tidy death. They were fraudulent images, coercively “bent on veiling reality.” And who within the family is conscripted to perpetuate, if not precisely to manufacture, such images? Women. In becoming wives, we’re made stewards of our husbands, sainted sucklers of children, menders of life’s ripped seams. After the dissolution of a decade-long marriage, Cusk turned from Christianity to the myths of antiquity and the unconscious, that “tempestuous Greek world of feeling.” We are beings born of chaos, after all, disciplined by institutions but governed by affects and actions that stretch past the limits of our knowing and detonate the illusion of social order.

MARRIAGE IS A GRIM BUSINESS—worse still if you’re a woman in a Rachel Cusk book. The blame lies with Christian iconography, she writes in her 2012 memoir, Aftermath, and pictures of the “holy family, that pious unit that sucked the world’s attention dry.” There, we found Mary and the manger, the Christ child, cuckolded Joseph: images gathered in a “cult of sentimentality and surfaces” to obscure the innate beastliness of human existence and so tidy death. They were fraudulent images, coercively “bent on veiling reality.” And who within the family is conscripted to perpetuate, if not precisely to manufacture, such images? Women. In becoming wives, we’re made stewards of our husbands, sainted sucklers of children, menders of life’s ripped seams. After the dissolution of a decade-long marriage, Cusk turned from Christianity to the myths of antiquity and the unconscious, that “tempestuous Greek world of feeling.” We are beings born of chaos, after all, disciplined by institutions but governed by affects and actions that stretch past the limits of our knowing and detonate the illusion of social order. The fastest supercomputer in the world is a machine known as Frontier, but even this speedster with nearly 50,000 processors has its limits. On a sunny Monday in April, its power consumption is spiking as it tries to keep up with the amount of work requested by scientific groups around the world. The electricity demand peaks at around 27 megawatts, enough to power roughly 10,000 houses, says Bronson Messer, director of science at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee, where Frontier is located. With a note of pride in his voice, Messer uses a local term to describe the supercomputer’s work rate: “They are running the machine like a scalded dog.”

The fastest supercomputer in the world is a machine known as Frontier, but even this speedster with nearly 50,000 processors has its limits. On a sunny Monday in April, its power consumption is spiking as it tries to keep up with the amount of work requested by scientific groups around the world. The electricity demand peaks at around 27 megawatts, enough to power roughly 10,000 houses, says Bronson Messer, director of science at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee, where Frontier is located. With a note of pride in his voice, Messer uses a local term to describe the supercomputer’s work rate: “They are running the machine like a scalded dog.”