Daniel Waldenström in Aeon:

Recent decades have seen private wealth multiply around the Western world, making us richer than ever before. A hasty glance at the soaring number of billionaires – some doubling as international celebrities – prompts the question: are we also living in a time of unparalleled wealth inequality? Influential scholars have argued that indeed we are. Their narrative of a new gilded age paints wealth as an instrument of power and inequality. The 19th-century era with low taxes and minimal market regulation allowed for unchecked capital accumulation and then, in the 20th century, the two world wars and progressive taxation policies diminished the fortunes of the wealthy and reduced wealth gaps. Since 1980, the orthodoxy continues, a wave of market-friendly policies reversed this equalising historical trend, boosting capital values and sending wealth inequality back towards historic highs.

The trouble with the powerful new orthodoxy that tries to explain the history of wealth is that it doesn’t fully square with reality. New research studies, and more careful inspection of the previous historical data, paint a picture where the main catalysts for wealth equalisation are neither the devastations of war nor progressive tax regimes. War and progressive taxation have had influence, but they cannot count as the main forces that led to wealth inequality falling dramatically over the past century. The real influences are instead the expansion from below of asset ownership among everyday citizens, constituted by the rise of homeownership and pension savings. This popular ownership movement was made possible by institutional changes, most important democracy, and followed suit by educational reforms and labour laws, and the technological advancements lifting everyone’s income.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Many writers’ graves are

Many writers’ graves are  I

I Welcome to Lit Trivia, the Book Review’s regular quiz about books, authors and literary culture. This week’s installment challenges you to identify classic novels from the descriptions in their original — and, well, not wholly positive — reviews in the pages of The New York Times. In the five multiple-choice questions below, tap or click on the answer you think is correct. After the last question, you’ll find links to the books if you’d like to do some further reading.

Welcome to Lit Trivia, the Book Review’s regular quiz about books, authors and literary culture. This week’s installment challenges you to identify classic novels from the descriptions in their original — and, well, not wholly positive — reviews in the pages of The New York Times. In the five multiple-choice questions below, tap or click on the answer you think is correct. After the last question, you’ll find links to the books if you’d like to do some further reading. A problem most of us have, perhaps especially women, is that when we are in the mood to have sex reinvent our lives—when we feel dirty, restless, eager to be used and witnessed—we lay around wishing for someone intuitive and creative to come along and recognize a kindred spirit in us. We walk into bars and parties as if we’re adolescents hoping to be recognized on the street by a talent scout. We know that if someone would just give us what we want, without us having to describe it, we would amaze them and ourselves. It humiliates and disappoints us when everyone who comes sniffing just feels “kind of… cheesy,” as you put it. The intention of sex voice is to conjure a mutual fantasy, to invoke a shared scene—but the question remains: Whose scene is it? We each have the opportunity (and, really, the imperative) to direct the erotic scene for ourselves—and this includes women who wish on the whole to be submissive. I don’t mean leading in sex; I mean adjusting, with a light touch, the direction in which we hope the scene will tend.

A problem most of us have, perhaps especially women, is that when we are in the mood to have sex reinvent our lives—when we feel dirty, restless, eager to be used and witnessed—we lay around wishing for someone intuitive and creative to come along and recognize a kindred spirit in us. We walk into bars and parties as if we’re adolescents hoping to be recognized on the street by a talent scout. We know that if someone would just give us what we want, without us having to describe it, we would amaze them and ourselves. It humiliates and disappoints us when everyone who comes sniffing just feels “kind of… cheesy,” as you put it. The intention of sex voice is to conjure a mutual fantasy, to invoke a shared scene—but the question remains: Whose scene is it? We each have the opportunity (and, really, the imperative) to direct the erotic scene for ourselves—and this includes women who wish on the whole to be submissive. I don’t mean leading in sex; I mean adjusting, with a light touch, the direction in which we hope the scene will tend.

T

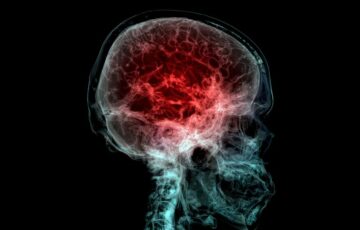

T In the more than six million years since people and chimpanzees split from their common ancestor, human brains have rapidly amassed tissue that helps decision-making and self-control. But the same regions are also the most at risk of deterioration during ageing, finds a study

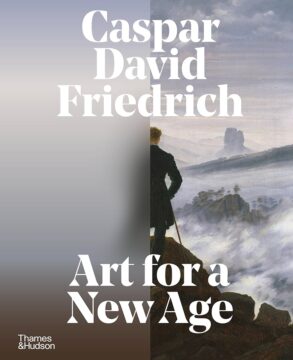

In the more than six million years since people and chimpanzees split from their common ancestor, human brains have rapidly amassed tissue that helps decision-making and self-control. But the same regions are also the most at risk of deterioration during ageing, finds a study The German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840), who is celebrated in these two books published to accompany the exhibitions in Hamburg and Berlin marking the 250th anniversary of his birth, has fascinated me all my life. When I was at school, his mysterious and emotive paintings started to appear on the covers of the grey-spined Penguin Modern Classics series: Abbey in the Oakwood on the cover of Hermann Hesse’s Narziss and Goldmund; Woman at a Window (the woman’s back turned, one shutter open to the spring morning and the riverbank) on that of Thomas Mann’s Lotte in Weimar. Covers featuring Sea of Ice, with its unfathomable grey-blue sky, and the yearning, autumnal Moonwatchers soon followed. Every image was memorable; every one hinted at emotional and spiritual depths embodied in northern European landscapes and places.

The German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840), who is celebrated in these two books published to accompany the exhibitions in Hamburg and Berlin marking the 250th anniversary of his birth, has fascinated me all my life. When I was at school, his mysterious and emotive paintings started to appear on the covers of the grey-spined Penguin Modern Classics series: Abbey in the Oakwood on the cover of Hermann Hesse’s Narziss and Goldmund; Woman at a Window (the woman’s back turned, one shutter open to the spring morning and the riverbank) on that of Thomas Mann’s Lotte in Weimar. Covers featuring Sea of Ice, with its unfathomable grey-blue sky, and the yearning, autumnal Moonwatchers soon followed. Every image was memorable; every one hinted at emotional and spiritual depths embodied in northern European landscapes and places.