Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

The Essay as Realm

Elisa Gabbert in Georgia Review:

I think this is important: memories and ideas happen in a place. An essay is a place for ideas; it has to feel like a place. It has to give one the feeling of entering a room.

I think this is important: memories and ideas happen in a place. An essay is a place for ideas; it has to feel like a place. It has to give one the feeling of entering a room.

The architect Christopher Alexander has written that “the experience of entering a building influences the way you feel inside the building.” “If the transition is too abrupt there is no feeling of arrival.” He cites a report called “Fairs, Exhibits, Pavilions, and their Audiences,” in which the authors describe observing people drift in and out of various exhibits, impassive and unengaged. There was one exhibit, however, where visitors had to cross a “huge, deep-pile, bright orange carpet on the way in.” The exhibit itself was no better than the others, they said, but people lingered there because they’d made a journey of sorts to enter. They’d crossed a kind of Willy Wonka or Wizard of Oz threshold, into a different realm. They felt changed.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Zombie Fungi Hijack Hosts’ Brains

Hannah Thomasy in The Scientist:

To the casual observer, the motivations that drive insect behaviors may appear quite simple: An insect might leave the nest to find food, wander around to seek out potential mates, or move into the sun or shade to maintain an optimal body temperature.

To the casual observer, the motivations that drive insect behaviors may appear quite simple: An insect might leave the nest to find food, wander around to seek out potential mates, or move into the sun or shade to maintain an optimal body temperature.

But sometimes the drivers of these behaviours are far more complex—and more sinister—than they first appear. In a surprisingly large number of cases, insects are not acting of their own free will in a way that benefits themselves or even their species. Instead, they have become “zombies,” controlled by barely visible fungal puppet masters that direct the insects’ behaviors, steering them into optimal conditions for dispersing infectious spores. While these fungi were described in the scientific literature as early as the mid-1800s, the extent and precision of the behavioral control that they exert on their unfortunate insect hosts—and the mechanisms they use to do so—are only just starting to be appreciated.1

As they begin to explore the complex molecular dialogue between these fungi and their insect hosts, scientists aren’t sure exactly what they will find. So far, the fungal kingdom as a whole has proven to be a rich source of bioactive metabolites; fungal-derived drugs are currently used as antibiotics, immunosuppressants, cholesterol-lowering agents, and migraine therapeutics, so there may be much to discover in these insect-manipulating species.2 “This is a group of fungi that haven’t quite been mined yet, for all the things that they might produce. I’m quite certain that we’ll bump into some interesting stuff,” said Charissa de Bekker, a molecular biologist who studies insect-fungi interactions at Utrecht University. This fascination has spread beyond the scientific community into pop culture, as evidenced by video games and movies like The Last of Us and The Girl with All the Gifts. So, although these fungi cannot literally infect humans, they have certainly extended their mycelia into the hearts of scientists and non-scientists alike.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

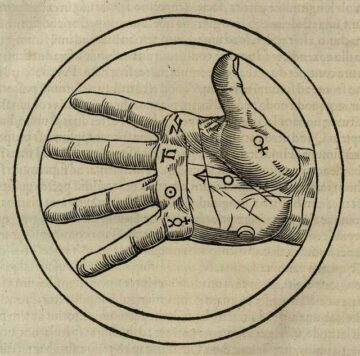

Chiromancy

Betsy Golden Kellem at JSTOR Daily:

Palm reading, also known as palmistry or chiromancy throughout history, has been far more than a party trick for centuries. Dating back to classical antiquity, the idea that a soothsayer can tell something about a person’s health, disposition, or destiny from the lines on their palm has long fascinated seers and scientists alike.

Palm reading, also known as palmistry or chiromancy throughout history, has been far more than a party trick for centuries. Dating back to classical antiquity, the idea that a soothsayer can tell something about a person’s health, disposition, or destiny from the lines on their palm has long fascinated seers and scientists alike.

Classicist Charles S. F. Burnett finds mentions of chiromancy in various ancient texts, including in Aristotle’s writing, but the practice of palm reading seems to have disappeared in the Western world between the classical era and the twelfth century. In an interesting blend of disciplines, records of the practice appear not only in scientific or magical writings but in religious text, too. Readers were advised that certain marks are auspicious.

“When it extends as far as the first finger, he will be a monk,” read a Latin chiromancy manuscript. “This mark is the sign of a parish income (presbyterium)…. This is a sign of someone being elected or freely blessing.”

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Decline of the Working Musician

Hua Hsu at The New Yorker:

Nicolay makes these gangs sound like a lot of fun, while also demystifying them. Some band people prefer hierarchy and assertive decision-makers; others aspire to a more chaotic kind of democracy. Some envy the star; others feel sorry for him. Jon Rauhouse, a musician who tours with the singer Neko Case, is glad not to be the one that interviewers want to speak with—he’s free to “go to the zoo and pet kangaroos.” Band people are often asked to interpret cryptic directives in the studio. The multi-instrumentalist Joey Burns recalls one singer who, in lieu of instructions, would tell him stories about the music—he might be told to imagine a song they were working on as “a cloud in the shape of an elephant, and it’s trying to squeeze through a keyhole to get into this room.”

Nicolay makes these gangs sound like a lot of fun, while also demystifying them. Some band people prefer hierarchy and assertive decision-makers; others aspire to a more chaotic kind of democracy. Some envy the star; others feel sorry for him. Jon Rauhouse, a musician who tours with the singer Neko Case, is glad not to be the one that interviewers want to speak with—he’s free to “go to the zoo and pet kangaroos.” Band people are often asked to interpret cryptic directives in the studio. The multi-instrumentalist Joey Burns recalls one singer who, in lieu of instructions, would tell him stories about the music—he might be told to imagine a song they were working on as “a cloud in the shape of an elephant, and it’s trying to squeeze through a keyhole to get into this room.”

Many musicians prefer the “emotional life” of the band to be familial, rather than seeing their bandmates as “a handful of co-workers.” And despite the collective dream that brings artists together, the critic and theorist Simon Frith argues, “the rock profession is based on a highly individualistic, competitive approach to music, an approach rooted in ambition and free enterprise,” which feeds perfectly into a quintessentially American zero-to-hero dream.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday Poem

The Keeper of Sheep

—an excerpt

The mystery of things, where is it?

If it exists, why doesn’t it at least appear

To show us that it is a mystery?

What does the river or the tree know of mystery?

And I, who am not more real that they are, what do I know of it?

Whenever I look at things and think what men think about them,

I laugh like a stream as it rushes over a stone.

Because the only hidden meaning of things

Is that they have to hidden meaning at all.

It is stranger than all strangenesses,

Than the dreams of all the poets

And the thoughts of all the philosophers,

That things really are what they seem to be

And there is nothing to understand.

Yes, this is what my senses learned on their own:—

Things have no signification: they have existence.

Things are the only hidden meaning of things.

by Fernando Pessoa

from The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro

New Directions Paperbooks 2020

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday, October 30, 2024

Bless You, Toxic Dwarf: An Appreciation of Gary Indiana

Ira Silverberg at Vulture:

Gary Indiana, who died on October 23 at 74 years old, was a brilliant and scathing critic of contemporary art and literature — and sometimes of those who thought they were his friends. His work at the Village Voice in the mid-to-late 1980s, when Jeff Weinstein edited him to perfect fever pitch, positioned him as the sharpest, most influential, and most feared art critic in New York of the time. It was a role that both defined and ruined him. He relied upon a persona that was about having come from nothing (not entirely the truth), knowing he wasn’t traditionally attractive to most men (he was short, skinny, and if he was ever a twink, those days were long past), was smart and used that to intimidate people, and eschewed money and fame (um, not really).

Gary Indiana, who died on October 23 at 74 years old, was a brilliant and scathing critic of contemporary art and literature — and sometimes of those who thought they were his friends. His work at the Village Voice in the mid-to-late 1980s, when Jeff Weinstein edited him to perfect fever pitch, positioned him as the sharpest, most influential, and most feared art critic in New York of the time. It was a role that both defined and ruined him. He relied upon a persona that was about having come from nothing (not entirely the truth), knowing he wasn’t traditionally attractive to most men (he was short, skinny, and if he was ever a twink, those days were long past), was smart and used that to intimidate people, and eschewed money and fame (um, not really).

Not exactly the usual art-world type, he left it and retreated into fiction, where he could work out his issues with characteristically dark humor in ultracontemporary social satires. He was full of contradictions, and his explanations of them were always brilliant and self-focused — plaintive, often exasperated wails from the last bohemian standing about the injustices he faced.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Charles Atlas | UNDER THE INFLUENCE

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Surprising Power of Piet Mondrian’s Lesser-Known Early Paintings

Nicholas Fox Weber at Literary Hub:

Approaching the age of twenty, Mondrian painted his most impressive painting to date. It was a still life of a dead hare. The animal hanging from its right hind leg is a feat of verisimilitude. The setting—the space above a wooden plank that recedes into a black background—is a triumph of austere elegance. The contrast between the luminous subject and the rich black presages Mondrian’s later abstractions.

Approaching the age of twenty, Mondrian painted his most impressive painting to date. It was a still life of a dead hare. The animal hanging from its right hind leg is a feat of verisimilitude. The setting—the space above a wooden plank that recedes into a black background—is a triumph of austere elegance. The contrast between the luminous subject and the rich black presages Mondrian’s later abstractions.

The canvas belongs above all to the tradition of Dutch still lifes as well as to pictures of freshly killed game by the French eighteenth-century painter Jean Siméon Chardin, but it is not a mere pastiche. It has a zing that goes far beyond the slavishness of a copy.

The sharp focus with which Mondrian renders the hare, and the elegance of the matte black background, have assurance without arrogance. With his renewed determination to be a painter, Mondrian had become his own man and developed his capacity to paint with a punch that energizes the viewer.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Largest Commercial Satellites Unfurl, Outshining Most of the Night Sky

Passant Rabie at Gizmodo:

The dawn of annoyingly massive satellites is upon us, shielding our views of the shimmering cosmos. Five of the largest communication satellites just unfolded in Earth orbit, and this is only the beginning of a Texas startup’s constellation of cellphone towers in space.

The dawn of annoyingly massive satellites is upon us, shielding our views of the shimmering cosmos. Five of the largest communication satellites just unfolded in Earth orbit, and this is only the beginning of a Texas startup’s constellation of cellphone towers in space.

AST SpaceMobile announced today that its first five satellites, BlueBirds 1 to 5, unfolded to their full size in space. Each satellite unfurled the largest ever commercial communications array to be deployed in low Earth orbit, stretching across 693 square feet (64 square meters) when unfolded. That’s bad news for astronomers as the massive arrays outshine most objects in the night sky, obstructing observations of the universe around us.

Things are just getting started for AST SpaceMobile, however, as the company seeks to create the first space-based cellular broadband network directly accessible by cell phones.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Charles Atlas Interview

Erica Getto and Charles Atlas at Bomb Magazine:

Sketch out Charles Atlas’s career, and the result might look like one of his multi-stream videos: disparate projections that, taken together, create a coherent portrait. To some, the artist and filmmaker is best known for these video collages and installations, featuring digitized numbers, people in motion, and abstract or geometric figures. Others might recognize him as a public broadcasting renegade whose TV specials bucked conventions of on-air programming with propulsive dancing, drag queens, chroma key, and startling audio. Since 2003, he’s drawn attention for his experiments with live multimedia performance. As a dance writer and film and television producer, I’ve long wanted to speak with Atlas about his pioneering work in “media-dance,” or dance on camera.

For nearly fifty years, Atlas has collaborated with choreographers and dancers to create vibrant, technically rigorous dance films. He first picked up a Super 8 camera in the early 1970s while stage-managing for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company and, soon after, became the company’s resident filmmaker. His early works with Cunningham involved technical challenges like filming in a mirrored studio without revealing the camera, or interspersing video monitors across a dance space.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Intricate model ships built by a Guantánamo prisoner

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

On Cat Memes, Cannibalism, and Election Lead-Up Laughter

Maggie Hennefeld in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

You can predict the outcome of the 2024 US presidential election by tracking the laughter in the room. Laughter glides on the edge of the unspeakable. It flirts with taboo obscenity and unbearable trauma while toeing the line and somehow lightening the tone. When Donald Trump absurdly accused Haitian migrants in Ohio of eating people’s pets, silly videos of armed feline militias vied for viral visibility with TikTok loops of dogs and cats reacting to debate footage off-screen. Meanwhile, the endlessly memeable specter of ALF—everyone’s favorite cat-eating TV sitcom alien from the planet Melmac—evoked the mock cannibalism of Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal” (1729), a Juvenalian pamphlet that offered to solve the Irish overpopulation and starvation crisis by serving up newborn infants “stewed, roasted, baked, or boiled.”

You can predict the outcome of the 2024 US presidential election by tracking the laughter in the room. Laughter glides on the edge of the unspeakable. It flirts with taboo obscenity and unbearable trauma while toeing the line and somehow lightening the tone. When Donald Trump absurdly accused Haitian migrants in Ohio of eating people’s pets, silly videos of armed feline militias vied for viral visibility with TikTok loops of dogs and cats reacting to debate footage off-screen. Meanwhile, the endlessly memeable specter of ALF—everyone’s favorite cat-eating TV sitcom alien from the planet Melmac—evoked the mock cannibalism of Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal” (1729), a Juvenalian pamphlet that offered to solve the Irish overpopulation and starvation crisis by serving up newborn infants “stewed, roasted, baked, or boiled.”

Like Swift’s furious satire, the viral meme culture of the 2024 election showdown between fragile democracy and resurgent fascism is responding to the apocalyptic political conjuncture with grotesque absurdity. As reality unravels, the jokes will only get weirder.

Intergenerational cannibalism has become more than a metaphor: the rich eating the poor’s offspring, Protestants gobbling up the papacy, Satanists pan-frying Christian progeny, outlandish conspiracy theories that human remains were found in Oprah Winfrey’s L.A. home.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday Poem

I’ve Been

trying all day

to remember that feeling

when you first meet someone

how a match

gets struck

on a rock

how you carry that fire

through each little task

and all day

the people you pass

notice the lights on

notice someone is home.

by Kay Cosgrove

from Echo Theo Review

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thrive Market CEO Nick Green On Staying Mission Driven

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Clinically Blind See Again With an Implant the Size of a Grain of Salt

Shelley Fan in Singularity Hub:

Seeing is believing. Our perception of the world heavily relies on vision.

Seeing is believing. Our perception of the world heavily relies on vision.

What we see depends on cells in the retina, which sit behind the eyes. These delicate cells transform light into electrical pulses that go to the brain for further processing. But because of age, disease, or genetics, retinal cells often break down. For people with geographic atrophy—a disease which gradually destroys retinal cells—their eyes struggle to focus on text, recognize faces, and decipher color or textures in the dark. The disease especially attacks central vision, which lets our eyes focus on specific things. The result is seeing the world through a blurry lens. Walking down the street in dim light becomes a nightmare, each surface looking like a distorted version of itself. Reading a book or watching a movie is more frustrating than relaxing. But the retina is hard to regenerate, and the number of transplant donors can’t meet demand. A small clinical trial may have a solution. Led by Science Corporation, a brain-machine interface company headquartered in Alameda, California, the study implanted a tiny chip that acts like a replacement retina in 38 participants who were legally blind.

Dubbed the PRIMAvera trial, the volunteers wore custom-designed eyewear with a camera acting as a “digital eye.” Captured images were then transmitted to the implanted artificial retina, which translated the information into electrical signals for the brain to decipher. Preliminary results found a boost in the participants’ ability to read the eye exam scale—a common test of random letters, with each line smaller than the last. Some could even read longer texts in a dim environment at home with the camera’s “zoom-and-enhance” function. The trial is ongoing, with final results expected in 2026—three years after the implant. But according to Frank Holz at the University of Bonn Ernst-Abbe-Strasse in Germany, the study’s scientific coordinator, the results are a “milestone” for geographic atrophy resulting from age.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday, October 29, 2024

When a cat saves your life: Review of “My Beloved Monster” by Caleb Carr

Kathryn Hughes in The Guardian:

In this exquisite book novelist Caleb Carr tells the story of the “shared existence” he enjoyed for 17 years with his beloved cat, Masha. At the time of writing she is gone, he is going, and all that remains is to explain how they made each other’s difficult lives bearable. The result is not just a lyrical double biography of man and cat but a wider philosophical inquiry into our moral failures towards a species which, cute internet memes notwithstanding, continues to get a raw deal.

In this exquisite book novelist Caleb Carr tells the story of the “shared existence” he enjoyed for 17 years with his beloved cat, Masha. At the time of writing she is gone, he is going, and all that remains is to explain how they made each other’s difficult lives bearable. The result is not just a lyrical double biography of man and cat but a wider philosophical inquiry into our moral failures towards a species which, cute internet memes notwithstanding, continues to get a raw deal.

Carr explains how Masha picked him as her person when he first visited the animal rescue centre nearly 20 years ago. She was a Siberian forest cat – huge, nearer to her wild self than most domestic moggies, and utterly delightful, a long-bodied streak of red-gold whose forward-facing eyes gave her the look of a delighted baby. The rescue centre staff are desperate that Carr take her, and equally anxious that he should understand what he is getting into. This cat, apparently, fights, bites and is unbothered about seeming grateful. But then, why should she be? Abandoned by her previous owners, she was locked in an apartment and left to die. It is an obscenity, says Carr, that goes on more often than we can bear to imagine.

Once Carr gets Masha – a name he hopes sounds vaguely Siberian – home to his farmhouse on Misery Mountain in upstate New York, she starts to show her true “wilding” nature.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Why Democracy Lives and Dies by Math

Siobhan Roberts in the New York Times:

“Math is power” is the tag line of a new documentary, “Counted Out,” currently making the rounds at festivals and community screenings. (It will have a limited theatrical release next year.) The film explores the intersection of mathematics, civil rights and democracy. And it delves into how an understanding of math, or lack thereof, affects society’s ability to deal with the most pressing challenges and crises — health care, climate, misinformation, elections.

“Math is power” is the tag line of a new documentary, “Counted Out,” currently making the rounds at festivals and community screenings. (It will have a limited theatrical release next year.) The film explores the intersection of mathematics, civil rights and democracy. And it delves into how an understanding of math, or lack thereof, affects society’s ability to deal with the most pressing challenges and crises — health care, climate, misinformation, elections.

“When we limit access to the power of math to a select few, we limit our progress as a society,” said Vicki Abeles, the film’s director and a former Wall Street lawyer.

Ms. Abeles was spurred to make the film in part in response to an anxiety about math that she had long observed in students, including her middle-school-age daughter. She was also struck by the math anxiety among friends and colleagues, and by the extent to which they tried to avoid math altogether. She wondered: Why are people so afraid of math? What are the consequences?

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Bernie Sanders Answers: “I disagree with Kamala’s position on the war in Gaza. How can I vote for her?”

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Donald Trump’s appearance on Joe Rogan is a watershed moment for new media

Sam Kahn at Persuasion:

The 2024 election will be “decided by podcasts,” Bobby Kennedy predicted in 2023—and that may be the line for which he is best remembered. The election is still a coin toss, but Trump has had momentum recently and may well have sealed a win this weekend with his appearance on Joe Rogan’s podcast—which, to me, felt like an historical moment. The significance of that appearance wasn’t just for this election. It was the moment where new media decisively replaced old.

The 2024 election will be “decided by podcasts,” Bobby Kennedy predicted in 2023—and that may be the line for which he is best remembered. The election is still a coin toss, but Trump has had momentum recently and may well have sealed a win this weekend with his appearance on Joe Rogan’s podcast—which, to me, felt like an historical moment. The significance of that appearance wasn’t just for this election. It was the moment where new media decisively replaced old.

Harris has done well in everything related to more traditional mass media. She presided over a successful Democratic National Convention. She out-debated Trump. But, around her, the hold of mass media is rapidly collapsing. Her anodyne 60 Minutes interview did more harm than good—the interview was almost perfectly bland, and all that anybody will remember of it is the revelation that 60 Minutes appeared to give her a mulligan on a muffed answer. Her brave decision to appear on Fox News may well have backfired—with Bret Baier subjecting her to a stinging interview that put Harris constantly on the defensive. And, in a real stab-in-the-back, both The Washington Post and Los Angeles Times—or, more specifically, their techie owners—broke with long-held precedent at the worst possible time to refrain from endorsing candidates.

None of this is Harris’ fault, exactly, but she’s fighting today’s war with yesterday’s weapons—or, more precisely, the weapons of several election cycles ago. Trump has consistently been ahead of her on podcasts.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.