Virginia Postrel in Works in Progress:

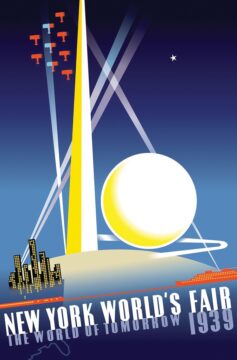

Progress used to be glamorous. For the first two thirds of the twentieth-century, the terms modern, future, and world of tomorrow shimmered with promise. Glamour is more than a synonym for fashion or celebrity, although these things can certainly be glamorous. So can a holiday resort, a city, or a career. The military can be glamorous, as can technology, science, or the religious life. It all depends on the audience. Glamour is a form of communication that, like humor, we recognize by its characteristic effect. Something is glamorous when it inspires a sense of projection and longing: if only . . .

Progress used to be glamorous. For the first two thirds of the twentieth-century, the terms modern, future, and world of tomorrow shimmered with promise. Glamour is more than a synonym for fashion or celebrity, although these things can certainly be glamorous. So can a holiday resort, a city, or a career. The military can be glamorous, as can technology, science, or the religious life. It all depends on the audience. Glamour is a form of communication that, like humor, we recognize by its characteristic effect. Something is glamorous when it inspires a sense of projection and longing: if only . . .

Whatever its incarnation, glamour offers a promise of escape and transformation. It focuses deep, often unarticulated longings on an image or idea that makes them feel attainable. Both the longings – for wealth, happiness, security, comfort, recognition, adventure, love, tranquility, freedom, or respect – and the objects that represent them vary from person to person, culture to culture, era to era. In the twentieth-century, ‘the future’ was a glamorous concept.

Joan Kron, a journalist and filmmaker born in 1928, recalls sitting on the floor as a little girl, cutting out pictures of ever more streamlined cars from newspaper ads. ‘I was fascinated with car design, these modern cars’, she says. ‘Industrial design was very much on our minds. It wasn’t just to look at. It was bringing us the future.’ Young Joan lived a short train ride from the famous 1939 New York World’s Fair, whose theme was The World of Tomorrow. She went again and again, never missing the Futurama exhibit. There, visitors zoomed across the imagined landscape of America in 1960, with smoothly flowing divided highways, skyscraper cities, high-tech farms, and charming suburbs. ‘This 1960 drama of highway and transportation progress’, the announcer proclaimed, ‘is but a symbol of future progress in every activity made possible by constant striving toward new and better horizons.’

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Lyric poets and mathematicians, by general agreement, do their best work young, while composers and conductors are evergreen, doing their best work, or more work of the same kind, as they age. Philosophers seem to be a more mixed bag: some shine early and some, like

Lyric poets and mathematicians, by general agreement, do their best work young, while composers and conductors are evergreen, doing their best work, or more work of the same kind, as they age. Philosophers seem to be a more mixed bag: some shine early and some, like  Anyway, in the video recording of The Cure performing A Forest for Dutch television in 1980 one encounters a version of The Cure that doesn’t quite jibe with later versions of the band. Robert Smith, in particular, has short spiky hair and looks nothing like the fully-coiffed gothic prince that he would soon become. He also looks annoyed or indifferent. And he has swapped instruments with Simon Gallup, the bassist for the band. Simon plays guitar in this live version. Robert Smith plucks away at the familiar bassline. Strange. Even stranger when one realizes that the strings on the bass are so slack there is no way they could be making any proper sound. And Robert Smith isn’t playing the notes correctly or in the right rhythm anyway.

Anyway, in the video recording of The Cure performing A Forest for Dutch television in 1980 one encounters a version of The Cure that doesn’t quite jibe with later versions of the band. Robert Smith, in particular, has short spiky hair and looks nothing like the fully-coiffed gothic prince that he would soon become. He also looks annoyed or indifferent. And he has swapped instruments with Simon Gallup, the bassist for the band. Simon plays guitar in this live version. Robert Smith plucks away at the familiar bassline. Strange. Even stranger when one realizes that the strings on the bass are so slack there is no way they could be making any proper sound. And Robert Smith isn’t playing the notes correctly or in the right rhythm anyway. There appear to be two types of drivers in North America these days: those who think about headlights only when one of theirs goes out, and those who fixate on them every time they drive at night. If you’re in the first camp, consider yourself lucky. Those in the second camp—aggravated by the excess glare produced in this new era of light-emitting diode headlights—are riled up enough that the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration receives more consumer complaints about headlights than any other topic, several insiders told me.

There appear to be two types of drivers in North America these days: those who think about headlights only when one of theirs goes out, and those who fixate on them every time they drive at night. If you’re in the first camp, consider yourself lucky. Those in the second camp—aggravated by the excess glare produced in this new era of light-emitting diode headlights—are riled up enough that the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration receives more consumer complaints about headlights than any other topic, several insiders told me. Noam Chomsky, one of the world’s most famous and respected intellectuals, will be 96 years old on Dec. 7, 2024. For more than half a century, multitudes of people have read his works in a variety of languages, and many people have relied on his commentaries and interviews for insights about intellectual debates and current events.

Noam Chomsky, one of the world’s most famous and respected intellectuals, will be 96 years old on Dec. 7, 2024. For more than half a century, multitudes of people have read his works in a variety of languages, and many people have relied on his commentaries and interviews for insights about intellectual debates and current events.

Many of the innovators who are advancing science, technology and culture are those whose unique cognitive abilities were identified and supported in their early years through enrichment programmes such as Johns Hopkins University’s

Many of the innovators who are advancing science, technology and culture are those whose unique cognitive abilities were identified and supported in their early years through enrichment programmes such as Johns Hopkins University’s  Jim and Louise

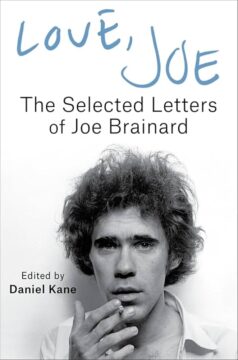

Jim and Louise This book review is a Trojan horse. Ostensibly it concerns a collection of letters titled “Love, Joe,” written by the downtown

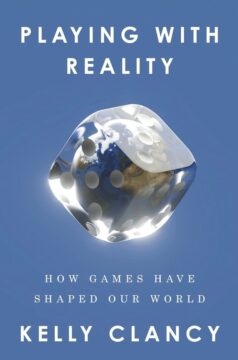

This book review is a Trojan horse. Ostensibly it concerns a collection of letters titled “Love, Joe,” written by the downtown  JULIEN CROCKETT: You dedicate Playing with Reality to the next generation, writing, “If play is the engine of creation, I cannot wait to see what new worlds you build.” A recurring theme in your book is the primacy of play and games to what it means to be human—that playing games is universal, an instinct. What makes games and play so important to understanding ourselves?

JULIEN CROCKETT: You dedicate Playing with Reality to the next generation, writing, “If play is the engine of creation, I cannot wait to see what new worlds you build.” A recurring theme in your book is the primacy of play and games to what it means to be human—that playing games is universal, an instinct. What makes games and play so important to understanding ourselves? I’m at DealBook Summit in NYC today and I just heard Sam Altman

I’m at DealBook Summit in NYC today and I just heard Sam Altman  Cass Sunstein: Well, I think that one mistake is that people think that universities are covered by the same principles, regardless of whether they’re public or private. And as a legal matter, public universities are governed by the First Amendment and private universities just aren’t. There’s also a lot of talk about incitement without a lot of clarity about what that particularly entails. So if I say something like, “If you don’t buy my book there’s going to be a revolution,” that’s kind of hopelessly useless talk on the part of an author and that would not be regulable as incitement.

Cass Sunstein: Well, I think that one mistake is that people think that universities are covered by the same principles, regardless of whether they’re public or private. And as a legal matter, public universities are governed by the First Amendment and private universities just aren’t. There’s also a lot of talk about incitement without a lot of clarity about what that particularly entails. So if I say something like, “If you don’t buy my book there’s going to be a revolution,” that’s kind of hopelessly useless talk on the part of an author and that would not be regulable as incitement. Nature’s survey — which took place before the US election in November — together with more than 20 interviews, revealed where some of the biggest obstacles to providing science advice lie. Eighty per cent of respondents thought policymakers lack sufficient understanding of science — but 73% said that researchers don’t understand how policy works. “It’s a constant tension between the scientifically illiterate and the politically clueless,” says Paul Dufour, a policy specialist at the University of Ottawa in Canada.

Nature’s survey — which took place before the US election in November — together with more than 20 interviews, revealed where some of the biggest obstacles to providing science advice lie. Eighty per cent of respondents thought policymakers lack sufficient understanding of science — but 73% said that researchers don’t understand how policy works. “It’s a constant tension between the scientifically illiterate and the politically clueless,” says Paul Dufour, a policy specialist at the University of Ottawa in Canada. To wake up one morning

To wake up one morning W

W