The Valentine is a Literary

The winter is still holding on, freezing moments.

A text congealed; a letter unopened is dramatic.

Dior’s burnt sienna lipstick, I purchased

from Amsterdam, is intact.

The lips slurp over coffee,

I recite Anna Akhmatova,

woodpecker-like, the cursor of dreams clicks

on the right stanza where we stop

made a vow to make an alternative interpretation

of her love poems.

The reason we are together after a year

is that lost interest in Austen,

and switched over to Lorca’s Ghazals,

and of Agha Shahid, who missed Kashmir,

like a beloved, still seeing in the mirror,

crumpled papers are in drawers,

an epistolary kiss, right where rhetoric begins,

letter writers indulge and boast about,

we are sending counter gazes,

passing through cold verandas,

it seems there is no epilogue.

by Rizwan Akhtar

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

“The freedom to write”: PEN America’s

“The freedom to write”: PEN America’s  Questions concerning the differences between Schelling’s and Hegel’s philosophical systems have always been of intense interest. This has been the case since Hegel decisively ended their friendship and collaboration by critically describing the early Schelling’s concept of the Absolute (the identity of identity and non-identity, or A=A [Dews, 75–76]) as the night “in which all cows are black” in the Phenomenology of Spirit in 1807 (Hegel 1977, 9, cf. Dews 75). Schelling’s Absolute, on Hegel’s account, was an abyss of darkness within which the dynamic development of real difference did not emerge. In contrast, Hegel thought his own dialectical system could lift difference out of the night, capturing the “reality of the finite” and the dynamic process of becoming (77). While Schelling quickly moved on from the “Identity System” in question, Hegel nevertheless remained an inescapable shadow haunting Schelling’s philosophical career.

Questions concerning the differences between Schelling’s and Hegel’s philosophical systems have always been of intense interest. This has been the case since Hegel decisively ended their friendship and collaboration by critically describing the early Schelling’s concept of the Absolute (the identity of identity and non-identity, or A=A [Dews, 75–76]) as the night “in which all cows are black” in the Phenomenology of Spirit in 1807 (Hegel 1977, 9, cf. Dews 75). Schelling’s Absolute, on Hegel’s account, was an abyss of darkness within which the dynamic development of real difference did not emerge. In contrast, Hegel thought his own dialectical system could lift difference out of the night, capturing the “reality of the finite” and the dynamic process of becoming (77). While Schelling quickly moved on from the “Identity System” in question, Hegel nevertheless remained an inescapable shadow haunting Schelling’s philosophical career. The further we get from Elvis Presley’s death, the more a crude music industry frame takes hold: the blinding flash of his Sun Records youth, the snowballing Hollywood banality, and the celebrity pill junkie slumped on his toilet, dead at 42. Praise Allah for recent documentaries like Elvis Presley: The Searcher (Thom Zimny, 2018), and the Reinventing Elvis: The ’68 Comeback (John Scheinfeld, 2023), where the performer’s radical charisma speaks for itself. In the same way that historic recreations always comment on their contemporary context, the Elvis Presley of Sun Studios and early RCA singles between 1954 and 1958 will always sound tantalizingly out of reach to 21st-century ears—another 80 years of laissez-faire racism will do that.

The further we get from Elvis Presley’s death, the more a crude music industry frame takes hold: the blinding flash of his Sun Records youth, the snowballing Hollywood banality, and the celebrity pill junkie slumped on his toilet, dead at 42. Praise Allah for recent documentaries like Elvis Presley: The Searcher (Thom Zimny, 2018), and the Reinventing Elvis: The ’68 Comeback (John Scheinfeld, 2023), where the performer’s radical charisma speaks for itself. In the same way that historic recreations always comment on their contemporary context, the Elvis Presley of Sun Studios and early RCA singles between 1954 and 1958 will always sound tantalizingly out of reach to 21st-century ears—another 80 years of laissez-faire racism will do that. The advent of advanced AI systems capable of generating academic text — including “chain-of-thought” large language models with test-time web access — is poised to significantly influence scholarly writing and publishing. This review discusses how academia, particularly in quantitative social science, should adjust over the next decade to AI-assisted or AI-written articles. We summarize the current capabilities of AI in academic writing (from drafting and citation support to idea generation), highlight emerging trends, and weigh advantages against risks such as misinformation, plagiarism, and ethical dilemmas. We then offer speculative predictions for the coming ten years, grounded in literature and present data on AI’s impact to date. An empirical analysis compiles real-world data illustrating AI’s growing footprint in research output. Finally, we provide policy and workflow recommendations for journals, peer reviewers, editors, and scholars, presented in an exhaustive table. Our aim is to inform a balanced approach to harnessing AI’s benefits in academic writing while safeguarding integrity

The advent of advanced AI systems capable of generating academic text — including “chain-of-thought” large language models with test-time web access — is poised to significantly influence scholarly writing and publishing. This review discusses how academia, particularly in quantitative social science, should adjust over the next decade to AI-assisted or AI-written articles. We summarize the current capabilities of AI in academic writing (from drafting and citation support to idea generation), highlight emerging trends, and weigh advantages against risks such as misinformation, plagiarism, and ethical dilemmas. We then offer speculative predictions for the coming ten years, grounded in literature and present data on AI’s impact to date. An empirical analysis compiles real-world data illustrating AI’s growing footprint in research output. Finally, we provide policy and workflow recommendations for journals, peer reviewers, editors, and scholars, presented in an exhaustive table. Our aim is to inform a balanced approach to harnessing AI’s benefits in academic writing while safeguarding integrity Sometime in the 1980s, an unprecedented change in the human condition occurred. For the first time in known history, the average person on Earth had enough to eat all the time.

Sometime in the 1980s, an unprecedented change in the human condition occurred. For the first time in known history, the average person on Earth had enough to eat all the time.

Fischer and his colleagues focused on detecting enzymes called proteases, which break down proteins and are active in tumours, even from the very early stages. They specifically looked at the activity of matrix metalloproteinases involved in chewing up collagen and the extracellular matrix, which helps tumours to invade the body.

Fischer and his colleagues focused on detecting enzymes called proteases, which break down proteins and are active in tumours, even from the very early stages. They specifically looked at the activity of matrix metalloproteinases involved in chewing up collagen and the extracellular matrix, which helps tumours to invade the body. For all the flowery adjectives and hyperbolic statements I’ve peddled through my writing over the past three years, I think that spur-of-the-moment assessment might be the most accurate statement about music I’ve ever verbalized. You could very well make the argument—as I suppose I am now—that the entire history of popular music (specifically in the U.K.) can be told through the life and career of Marianne Faithfull. There is a version of that history which I had been sold as a young person, just hungry to learn as much as I could. Yet, my reading and life experience over time have created a slow process of realizing I barely exist in that history—that the so-called “progressive” history of New Hollywood and the rock era mainly spelt freedom for those who already had it. I would never deny the importance or quality of so much of that work, but double-standards present themselves the second you start scratching away at the carefully-maintained patina of “rock history.”

For all the flowery adjectives and hyperbolic statements I’ve peddled through my writing over the past three years, I think that spur-of-the-moment assessment might be the most accurate statement about music I’ve ever verbalized. You could very well make the argument—as I suppose I am now—that the entire history of popular music (specifically in the U.K.) can be told through the life and career of Marianne Faithfull. There is a version of that history which I had been sold as a young person, just hungry to learn as much as I could. Yet, my reading and life experience over time have created a slow process of realizing I barely exist in that history—that the so-called “progressive” history of New Hollywood and the rock era mainly spelt freedom for those who already had it. I would never deny the importance or quality of so much of that work, but double-standards present themselves the second you start scratching away at the carefully-maintained patina of “rock history.” T

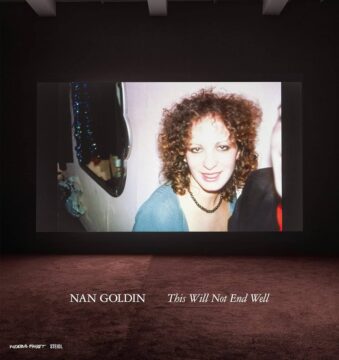

T Goldin’s sharp eye makes her stories simple, but it doesn’t make them easy. Sisters, Saints and Sibyls (2004-22) is a tribute to her elder sister, Barbara, who was institutionalised when she hit puberty and killed herself aged eighteen. A few years later, Nancy – as she was then – ran away from home. She was fostered and in 1968 landed in a ‘hippy free school’ called Satya, in Massachusetts. She spent as much time as she could at the Brattle Theatre and the Orson Welles cinema in Cambridge. The school had a grant from Polaroid, which was based nearby, and Goldin was one of the students given a camera. ‘Photography,’ she said recently, ‘was a way to walk through fear.’ As a teenager she was reticent and barely spoke, but became friends with a fellow student (and fellow photographer), David Armstrong. The camera became a solution to the problems of childhood, of growing up, of what was happening to her now – a way of proving her experiences were real.

Goldin’s sharp eye makes her stories simple, but it doesn’t make them easy. Sisters, Saints and Sibyls (2004-22) is a tribute to her elder sister, Barbara, who was institutionalised when she hit puberty and killed herself aged eighteen. A few years later, Nancy – as she was then – ran away from home. She was fostered and in 1968 landed in a ‘hippy free school’ called Satya, in Massachusetts. She spent as much time as she could at the Brattle Theatre and the Orson Welles cinema in Cambridge. The school had a grant from Polaroid, which was based nearby, and Goldin was one of the students given a camera. ‘Photography,’ she said recently, ‘was a way to walk through fear.’ As a teenager she was reticent and barely spoke, but became friends with a fellow student (and fellow photographer), David Armstrong. The camera became a solution to the problems of childhood, of growing up, of what was happening to her now – a way of proving her experiences were real.