Stephen Smith at The Guardian:

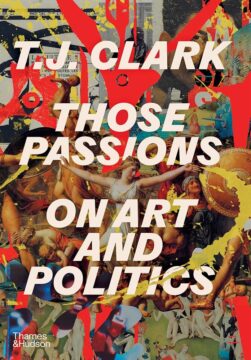

Politics runs through the history of art like a protester in a museum with a tin of soup. From emperors’ heads on coins to Picasso’s anti-war masterpiece, Guernica, and Banksy’s street art, power and visual culture have been closely and sometimes combustibly associated. This relationship is explored in essays by the distinguished art historian TJ Clark, professor emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley. Many of them first appeared in the London Review of Books, where the academic is given room to dilate in its rather airless pages. He brings a wide scholarship and unflagging scrutiny to his task. That said, his introduction includes the discouraging spoiler: “art-and-politics [is] hell to do”. From time to time, the reader finds themselves recalling this damning admission.

Politics runs through the history of art like a protester in a museum with a tin of soup. From emperors’ heads on coins to Picasso’s anti-war masterpiece, Guernica, and Banksy’s street art, power and visual culture have been closely and sometimes combustibly associated. This relationship is explored in essays by the distinguished art historian TJ Clark, professor emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley. Many of them first appeared in the London Review of Books, where the academic is given room to dilate in its rather airless pages. He brings a wide scholarship and unflagging scrutiny to his task. That said, his introduction includes the discouraging spoiler: “art-and-politics [is] hell to do”. From time to time, the reader finds themselves recalling this damning admission.

Clark writes from a “political position on the left”. He reflects on epoch-making events such as the Russian revolution, which spawned socialist realist art. He says the Dresden-born artist Gerhard Richter, 93, maker of abstract and photorealist works, is “haunted by his past” in the former East Germany.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Rap is original poetry recited in rhythm and rhyme over prerecorded instrumental tracks. Rap music (also referred to as rap or hip-hop music) evolved in conjunction with the cultural movement called hip-hop. Rap emerged as a minimalist street sound against the backdrop of the heavily orchestrated and formulaic music coming from the local house parties to dance clubs in the early 1970s. Its earliest performers comprise MCs (derived from master of ceremonies but referring to the actual rapper) and DJs (who use and often manipulate pre-recorded tracks as a backdrop to the rap), break dancers and graffiti writers.

Rap is original poetry recited in rhythm and rhyme over prerecorded instrumental tracks. Rap music (also referred to as rap or hip-hop music) evolved in conjunction with the cultural movement called hip-hop. Rap emerged as a minimalist street sound against the backdrop of the heavily orchestrated and formulaic music coming from the local house parties to dance clubs in the early 1970s. Its earliest performers comprise MCs (derived from master of ceremonies but referring to the actual rapper) and DJs (who use and often manipulate pre-recorded tracks as a backdrop to the rap), break dancers and graffiti writers.

Political outcomes would be relatively simple to predict and understand if only people were well-informed, entirely rational, and perfectly self-interested. Alas, real human beings are messy, emotional, imperfect creatures, so a successful theory of politics has to account for these features. One phenomenon that has grown in recent years is an alignment of cultural differences with political ones, so that polarization becomes more entrenched and even violent. I talk with political scientist Lilliana Mason about how this has come to pass, and how democracy can deal with it.

Political outcomes would be relatively simple to predict and understand if only people were well-informed, entirely rational, and perfectly self-interested. Alas, real human beings are messy, emotional, imperfect creatures, so a successful theory of politics has to account for these features. One phenomenon that has grown in recent years is an alignment of cultural differences with political ones, so that polarization becomes more entrenched and even violent. I talk with political scientist Lilliana Mason about how this has come to pass, and how democracy can deal with it. Monterroso has often been compared to Borges, and the comparisons are generally pretty apt. Both writers preoccupied themselves, formally, with short stories and essays that seem to merge into one another; both had a playful interest in scholarly arcana; both were obsessed with the question of style; and both were fascinated by parables and fables. But compared with the ironclad intertextuality of a writer like Borges, Monterroso’s own brand of self-referentiality isn’t exactly philosophically sound—a result, probably, of his antic disposition. It doesn’t approach, or even attempt to approach, the ideal of a closed system. Read a Borges story, and you often get a sense of the author going solemnly about his work like a monk. In a Monterroso story, the image called to mind is rather that of a clerk—one who is lazy, or bad at his job, or poorly trained, or some combination of the three. Things seem simply to have been misfiled.

Monterroso has often been compared to Borges, and the comparisons are generally pretty apt. Both writers preoccupied themselves, formally, with short stories and essays that seem to merge into one another; both had a playful interest in scholarly arcana; both were obsessed with the question of style; and both were fascinated by parables and fables. But compared with the ironclad intertextuality of a writer like Borges, Monterroso’s own brand of self-referentiality isn’t exactly philosophically sound—a result, probably, of his antic disposition. It doesn’t approach, or even attempt to approach, the ideal of a closed system. Read a Borges story, and you often get a sense of the author going solemnly about his work like a monk. In a Monterroso story, the image called to mind is rather that of a clerk—one who is lazy, or bad at his job, or poorly trained, or some combination of the three. Things seem simply to have been misfiled. Christopher Nolan’s film The Prestige presents a three-act structure said to apply to all great magic tricks. First is the pledge: the magician presents something ordinary, though the audience suspects that it isn’t. Next is the turn: the magician makes this ordinary object do something extraordinary, like disappear. Finally, there’s the prestige: the truly astounding moment, as when the object reappears in an unexpected way.

Christopher Nolan’s film The Prestige presents a three-act structure said to apply to all great magic tricks. First is the pledge: the magician presents something ordinary, though the audience suspects that it isn’t. Next is the turn: the magician makes this ordinary object do something extraordinary, like disappear. Finally, there’s the prestige: the truly astounding moment, as when the object reappears in an unexpected way. In Washington, DC, the city currently home to America’s least popular president ever, the mainstream media “broke” the story that a rash of black girls had gone missing. Social networking platforms circulated hashtags and headlines speculating the girls had been abducted and forced into sex work. Others worried the girls were dead. The police countered all theories by assuring local and national worriers that these missing black girls were merely runaways.

In Washington, DC, the city currently home to America’s least popular president ever, the mainstream media “broke” the story that a rash of black girls had gone missing. Social networking platforms circulated hashtags and headlines speculating the girls had been abducted and forced into sex work. Others worried the girls were dead. The police countered all theories by assuring local and national worriers that these missing black girls were merely runaways.

It is reasonable to assume that more than 15 months of pulverizing conflict have changed the perceptions of ordinary civilians in the territory about what they want for their future, how they see their land, who they think should be their rulers, and what they consider to be the most plausible pathways to peace. Given the extraordinary price they have paid for Hamas’s actions on October 7, 2023, Gazans might be expected to reject the group and favor a different leadership. Similarly, outside observers might anticipate that after so much hardship, Gazans would be more prepared to compromise on larger political aspirations in favor of more urgent human needs.

It is reasonable to assume that more than 15 months of pulverizing conflict have changed the perceptions of ordinary civilians in the territory about what they want for their future, how they see their land, who they think should be their rulers, and what they consider to be the most plausible pathways to peace. Given the extraordinary price they have paid for Hamas’s actions on October 7, 2023, Gazans might be expected to reject the group and favor a different leadership. Similarly, outside observers might anticipate that after so much hardship, Gazans would be more prepared to compromise on larger political aspirations in favor of more urgent human needs.