Clifford Thompson at Commonweal:

“For generations in the mind of America, the Negro has been more of a formula than a human being—a something to be argued about, condemned or defended, to be ‘kept down,’ or ‘in his place,’ or ‘helped up,’ to be worried with or worried over, harassed or patronized, a social bogey or a social burden.” So wrote Alain Locke in the anthology The New Negro (1925), often considered the founding document of the Harlem Renaissance, the artistic movement of which Locke is generally recognized as intellectual impresario. “The thinking Negro even has been induced to share this same general attitude, to focus his attention on controversial issues, to see himself in the distorted perspective of a social problem. His shadow, so to speak, has been more real to him than his personality.”

“For generations in the mind of America, the Negro has been more of a formula than a human being—a something to be argued about, condemned or defended, to be ‘kept down,’ or ‘in his place,’ or ‘helped up,’ to be worried with or worried over, harassed or patronized, a social bogey or a social burden.” So wrote Alain Locke in the anthology The New Negro (1925), often considered the founding document of the Harlem Renaissance, the artistic movement of which Locke is generally recognized as intellectual impresario. “The thinking Negro even has been induced to share this same general attitude, to focus his attention on controversial issues, to see himself in the distorted perspective of a social problem. His shadow, so to speak, has been more real to him than his personality.”

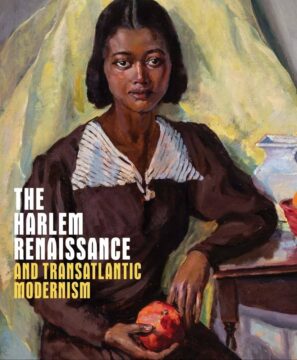

However, Locke added, “By shedding the old chrysalis of the Negro problem we are achieving something like a spiritual emancipation.” That emancipation largely took the form of creative expression—the literature, music, and visual art that flowered in the 1920s and ’30s and reflected the experiences of millions of African Americans who, seeking opportunity, migrated from the South to the cities of the North and Midwest.

more here.